FEMA Celebrates 40th Anniversary with Talk of More Change

The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) marked its 40th anniversary on April 1. It is hard to imagine disaster management today without the involvement and support of FEMA.

It is also hard to imagine any discussion about FEMA without talking about change. During its 40-year history, the Agency has been in an almost constant state of transformation.

FEMA was created by President Jimmy Carter in 1979 with the consolidation of a number of federal agencies. With one stroke of the pen, FEMA absorbed the emergency preparedness and response roles from the Federal Insurance Administration, the National Weather Service Community Preparedness Program, the Federal Preparedness Agency of the General Services Administration, the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Federal Disaster Assistance Administration, and civil defense responsibilities from the Department of Defense Civil Preparedness Agency.

After the terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001, another consolidation took place and FEMA became part of the Department of Homeland Security, along with such agencies as the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, U.S. Customs and Border Protection, U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement, the Transportation Security Administration, U.S. Coast Guard and the National Protection and Programs Directorate.

But there is more. As the Agency itself describes on its website: “In response to perceived shortcomings to large disasters such as Hurricanes Andrew, Katrina and Sandy, Congress passed legislation modifying or adding to FEMA’s role.”

Last year on Oct. 5, President Trump signed the Disaster Recovery Reform Act of 2018 into law, which, as FEMA indicates, “these reforms acknowledge the shared responsibility of disaster response and recovery, aim to reduce the complexity of FEMA and build the nation’s capacity for the next catastrophic event.” The law contains more than 50 provisions that require FEMA policy or regulation changes for full implementation, as they amend the Robert T. Stafford Disaster Relief and Emergency Assistance Act.

It is too early to tell exactly what “shared responsibility” will actually mean. Suffice it to say there is growing resistance to the high costs the federal government is absorbing in response to the catastrophic disasters we have experienced over the last few years.

Emergency federal support for disasters has also become something of a political football. Disaster aid comes in two paths: as an annual disaster appropriation to FEMA (as well as other federal agencies), called the Disaster Relief Fund that is part of the federal government’s budget process or as a special, one-time-only supplemental funding for specific disasters. The special appropriation for Katrina went through relatively easily. Special appropriations for Sandy-impacted areas received $60 billion from Congress, with significant grumbling from some legislators who complained it was a boondoggle. When Congress began discussions about support after Harvey, Maria and Irma, legislators initially complained about the previous resistance to Sandy relief, but ultimately went along.

Congress has now been debating since December about a new disaster aid package that addresses damage from hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires, flooding and other natural disasters and includes relief for farmers, assistance for veterans’ health facilities, money to restore highways and numerous other provisions. President Trump has not made reaching a decision any easier by complaining about too much support for Puerto Rico. As of this writing, the bill is still stalled.

So what should Congress do? Here are my three simple solutions:

- Budget for Disasters. Disasters will undoubtedly occur this year, so why not budget for them? This is the same advice we give foundations and corporations: think ahead – do not wait until the disaster happens before taking action. Disaster funding should not have to be an emergency. Special appropriations for disasters inevitably lead to political wrangling, funding add-ons not associated with disasters, increases in the federal budget deficit and lopsided funding priorities. Maya MacGuineas points out in an op-ed in The Hill that the federal government allocated more on recovery efforts following Hurricane Sandy than it did that year on higher education, agriculture or the Department of Homeland Security. The American public would be better served if emergency disaster relief became part of the regular budget process.

- Require more Investments in Planning, Preparation and Long-Term Recovery. Emergency appropriations are always reactions to disasters. A better approach would be to invest more money in planning, preparation and mitigation—well ahead of any disasters. FEMA is finally starting to think about mitigation, but it is taking a long time to roll out and it could be doing more. Why not require every state to have a resilience plan, one that reaches every community? An idea first posed by former FEMA director Craig Fugate, is still floating around, and still makes sense: allocate federal dollars to states based on the amount of effort they are undertaking to plan and prepare for disasters. Those that actively work to mitigate disasters would receive proportionally more than those states that pretend disasters will not happen. As Fugate explained to Emergency Management: “states would chip in a certain amount of money — a ‘deductible’ — before they can get a presidential declaration. FEMA would be able to reduce those deductibles for states that took steps to lower the costs of disasters by, for example, imposing more stringent building codes in coastal areas or thinning forests where wildfires are likely.” A report released by the National Institute of Building Sciences last year found that every $1 invested in preventative efforts translated to $6 saved later in relief and recovery expenses.

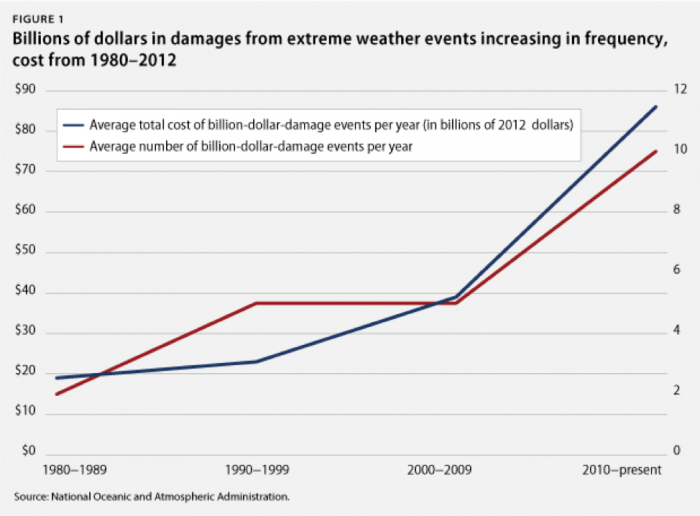

- Finally, it is time to recognize that climate change requires bold action. A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report listed the federal government’s fiscal exposure to disaster assistance as a “high risk.” Its report included this bold statement: “According to the November 2018 Fourth National Climate Assessment, neither global efforts to reduce emissions nor regional resilience efforts approach the scales need to avoid substantial damages over the coming decades. To reduce its fiscal exposure, the federal government needs a cohesive strategic approach with strong leadership and the authority to manage risks across the entire range of related federal activities.”

Clearly federal government disaster policies need to keep changing – and quickly. The changes I propose would represent more significant changes for FEMA but these are changes we need to implement soon so when people look back 40 years from now they will know we took the increasing frequency and intensity of disasters seriously and did everything in our power to mitigate the impacts.

What do you think? I’d love to hear your thoughts on changes you would like to see at FEMA and in federal government disaster policies. You can write to me at: bob.ottenhoff@disasterphilanthropy.org.

More like this