The Future of Our Cities & Communities Depends on Urban Resiliency

This blog originally appeared on Meeting of the Minds.

What are philanthropic donors thinking about urban resilience? It depends on your definition of urban resilience. Is it advocacy for stronger building codes? Support for preparedness, recovery or mitigation? Training and support of vulnerable populations? Or a combination of all these and many more?

At the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP), we advise corporations and foundations on how to make their disaster-related giving strategic and impactful. Our research has found that very few institutional donors have regular grantmaking programs dedicated to disasters and there are only a handful of foundations with program staff focused on disasters. Instead, contributions tend to be episodic and occasional in nature. Amounts fluctuate considerably based on the year’s events. Some foundations address disasters through their normal grantmaking lenses, such as children, vulnerable populations or economic development, rather than something called specifically “disasters.”

When considering urban resilience, I start with the definition by the Rockefeller Foundation: “the ability to survive and thrive in the face of increasingly unpredictable natural or manmade disasters, often spurred by climatic change or hiccups in the global economy.”

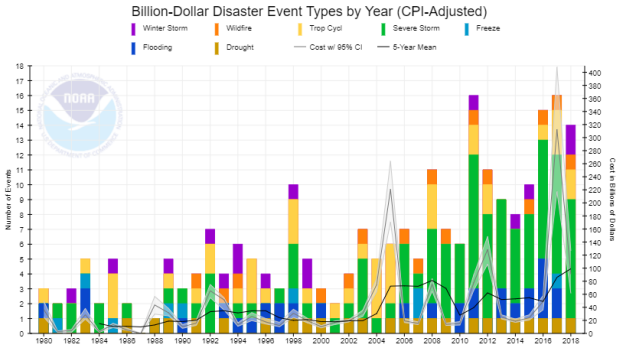

There are sound reasons for philanthropic organizations to be supporting efforts at strengthening resiliency. In 2017, the United States experienced 16 major natural disasters that each resulted in $1 billion or more in damage. Hundreds of other smaller-scale disasters struck the nation as well, causing in total at least $320 billion in damage – the most ever in a single year. This past year brought two major hurricanes, massive wildfires, significant floods, volcanic eruptions, super typhoons, major earthquakes and devastating tsunamis, with at least 14 $1 billion disasters in the U.S.

Part of the increase in estimated damage costs is due to the increase in the frequency and intensity of disasters. Contributing factors include increased urbanization and growing populations. Here in the U.S., we have seen significant population growth in vulnerable coastal areas and in places with a history of frequent wildfires that worsen impacts when disasters strike.

American individuals, foundations and corporations typically respond to these catastrophes with an immediate and incredible outpouring of donations of cash, volunteer time, products and services. It is estimated that over $1 billion was donated in the aftermath of 2017’s

Hurricane Harvey alone, a storm that impacted Houston and 41 counties in southeast Texas. By comparison, donated amounts to subsequent Hurricanes of Irma and Maria in 2017 and Florence and Michael in 2018 were considerably lower – storms that generally hit less urban areas.

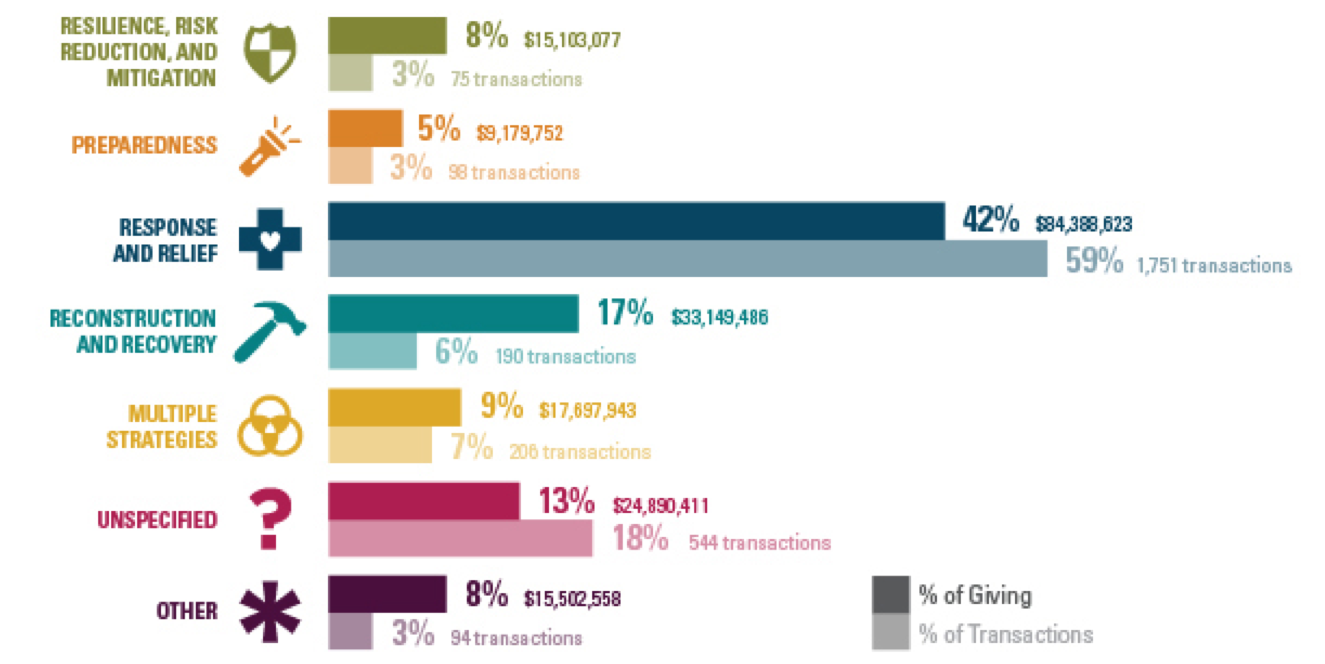

Our research has found that the vast majority of contributions go to immediate relief and are given within thirty days of a disaster occurring. Relatively small amounts are giving to planning, preparation, mitigation and even long-term recovery. Contributions directly to resilience programs are tiny.

Although the word “resilience” has been used for many years in both disaster and non-disaster settings, probably no single philanthropic entity has done more to promote and define the concept of resilience than the Rockefeller Foundation. Over the last decade, by its own count, more than a half billion dollars in grants have been awarded to advance the concept of resilience.

Superstorm Sandy sharpened the Foundation’s approach because it underscored just how complacent cities could be. Judith Rodin, then CEO noted, “New York has viewed itself as quite resilient, and there was a great deal of real and significant attention and investment after 9/11 to becoming more resilient – and yet Sandy was catastrophic.”

The reality is, until resilience is built into the priorities, budgets and culture of cities, disruptions – natural or manmade – can turn into disasters. However, this escalation needn’t be inevitable. Indeed, with an integrated approach to resilience, disruption can be turned to advantage. Within each crisis lies an opportunity.

Seeking ways to increase its impact and leverage its investments, in 2013 the Rockefeller Foundation launched 100 Resilient Cities (100RC) which took a comprehensive approach to resiliency. Adding to the impact, thinking broadly by including natural disasters, civil disturbances, economic disruptions and other potentially disruptive events also helped build political constituencies and collaborations.

The 100RC approach to infrastructure also appealed to cash-strapped cities. Rather than solely focusing on building a new highway, for example, the 100RC approach to resiliency suggested looking for multiple benefits like a new highway project that doubles as a water barrier along a river that also provides new recreational opportunities. Resiliency underscored the new mantra that “single uses of infrastructure are over.”

In late 2018, the Urban Institute released an independent assessment of 100RC (funded by Rockefeller Foundation) that found member cities are widely adopting holistic resilience planning practices and “de-siloing” city operations to tackle social, economic and physical challenges. Moreover, the analysis found 100RC is among the first global urban initiatives to employ a consistent set of tools, supports and resources across so many diverse cities for which no alternative exists.

Findings suggest 100RC is contributing positively to six key areas of interest in its member cities by embedding resilience principles in city planning and operations, including:

- Explication of resilience in city planning.

- Internal consistency across cities’ various planning documents.

- Establishment of a Chief Resilience Office or similar cross-sectoral coordinator.

- Reduction in the strength of government silos that promote ineffective solutions, duplication and inefficiency.

- Better collaboration across city, state and national levels of government.

- Changes to budgetary review procedures or leveraged funds for resilience-building efforts that may ultimately lead to more efficient and effective use of city funds.

Find the current list of member cities here: www.100resilientcities.org/cities.

Despite the apparent success, in April 2019, the Rockefeller Foundation announced it would disband Resilient Cities and no longer have dedicated staff. Its work, which had been supported by $164 million from Rockefeller in six years of existence, will be directed to other “pathways,” according to a statement by 100 Resilient Cities President Michael Berkowitz.

Will the resilient cities movement, sparked by Rockefeller, make a difference for cities in the long run? Or will this end up only as a grant program that allowed cities to briefly do something they otherwise could not—or would not—have done? Will “resilience officers” make a sufficient enough difference to earn ongoing funding within a city budget or will they be pushed aside by more urgent priorities? For philanthropy, another big question will be whether this movement can migrate from a Rockefeller Foundation inspired effort into one with broad support within the philanthropic community. Only time will tell whether these and other issues are sufficiently addressed so that building urban resilience becomes a movement.

Meanwhile, there are more modest examples of efforts underway to build urban resiliency.

One is Rebuild By Design. It began as a design competition launched by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) in partnership with nonprofit organizations and the philanthropic sector, in response to Superstorm Sandy’s devastating impact. In June 2013, it launched a multi-stage planning and design competition to promote resilience in the Sandy-affected region. Today, Rebuild By Design is in ten locations, including six American cities: San Francisco, Atlanta, Boston, Oakland, Boulder and Los Angeles. Projects include studying coastal areas, housing, transportation and climate change. In all these programs, Rebuild By Design looks for a multi-dimensional approach, with collaborations between designers, researchers, community members, government officials and subject matter experts.

Some of CDP’s own resilience work on Hurricane Harvey recovery is supporting efforts in and around Houston. The first challenge leaders faced in these communities was how to build back. Unquestionably, there was a sense of urgency to restore order. However, it is not only impractical but also unwise to build back and experience the same traumas following the next disaster. Is it possible to build back in a way to be in an improved position to endure future challenges? We believe so. The CDP Hurricane Harvey Recovery Fund is finding ways to build community resiliency – capacity building for local organizations, affordable housing initiatives, a mobile mental health unit for Texas Children’s Hospital, legal services for underserved populations, among others. Our holistic, targeted and localized approach to grantmaking is another example of how philanthropy can have transformative impacts in building resiliency.

And in Puerto Rico, as we do with all our recovery funds, CDP contacted other donors to learn about their funding activities; researched what local nonprofit service providers were doing; and identified funding and service gaps. Ultimately, our grants committee concluded that our funding could make the most significant difference by focusing on: 1) food security, 2) health and mental health needs of older adults and 3) livelihoods and economic recovery for communities.

One notable project is in San Juan where we are part of the effort, led by The Solar Foundation and the Clinton Foundation, for the installation of solar and energy efficiency upgrades of the Plaza del Mercado de Río Piedras in San Juan, the largest produce market on the island, responsible for the livelihoods of 200 small business owners. Since Hurricane Maria, the energy situation has led to an unstable business environment. A $600,000 grant from The Hispanic Foundation and a $500,000 grant from CDP will cover the cost of the purchase and installation of the first phase of solar panels, battery capacity and LED lighting. Our grant also creates an apprenticeship program for local workers to learn skills related to solar installation, roofing and electrical work which will help promote local workforce development. The project is being done at the request of, and in close coordination with, the Municipality of San Juan.

The last decade has brought enormous natural disasters that have philanthropic leaders re-thinking their approaches. Merely funding immediate relief is no longer sufficient. Solely reacting to disasters is no longer sustainable.

New approaches that strategically support all phases of disasters—from planning to mitigation to recovery to resilience—are increasingly being addressed. The Rockefeller Foundation’s major investment revealed a real desire among cities to do more with resilience. CDP’s work in disaster areas, with a focus on medium- to long-term recovery expands the concept.

As with any large-scale commitment of tax dollars and philanthropic support, applying resources in an equitable manner is essential. There are stark considerations. Whose community are we making resilient? And at what cost? Who is being left behind? If not carefully undertaken, the resiliency movement could experience some of the pitfalls of the urban planning movement of the 1950’s and 1960’s where decades later we more fully understand the negative consequences of large-scale destruction and rebuilding of neighborhoods, and more clearly see those who benefited from the movement and those who lost out.

The hopeful signs of the resilience movement are only a beginning. The relatively few philanthropic commitments to resilience do not yet represent a philanthropic trend. However, they indicate a growing recognition that philanthropic contributions to disaster-related activities need to be aware of the full life cycle and can make a significant difference in creating more resilient cities, better able to withstand crises.

More like this

Announcing the 2018 Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund