The Many Crises of Nepal

After living in Kathmandu in the 1990s and last visiting in April 2000, it was a shock to return last December. In many places, it was hardly recognizable. Not because of the destruction caused by twin earthquakes last spring, but rather by all of the growth since I last was there. New, tall glass buildings […]

After living in Kathmandu in the 1990s and last visiting in April 2000, it was a shock to return last December. In many places, it was hardly recognizable. Not because of the destruction caused by twin earthquakes last spring, but rather by all of the growth since I last was there. New, tall glass buildings are everywhere, and where the city once blended into country fields, now there are dense neighborhoods and multi-laned highways for miles. It wasn’t the Kathmandu I expected to see after the massive quakes. But it was still awe-inspiring and gave me hope.

It wasn’t that we didn’t see evidence of the earthquake’s destruction. We did. In the form of red bricks and dust (that ubiquitous symbol of re-building), old wooden buildings braced with 4x4s so that they wouldn’t topple forward as the hustle and bustle continued below, and camps for the still displaced–one contrastingly placed next to the brand new Hyatt Regency. We heard so many disaster stories from our friends–stories about what happened when the ground shook, where they stayed in those first few weeks, the damage that they saw, and how their neighbors and communities came together to help each other.

I had spent a lot of time in New Orleans after the levee failures and was amazed at how similar these personal stories were to the ones I heard there, particularly with regards to the role of person-to-person aid and the failures of the bigger entities and government. I was also struck by how certain visuals stood out to me–in New Orleans, it was the blue tarps on the roofs; In Nepal, it is the piles of red bricks.

Our trip also took place four months into an energy crisis. In September, petrol and propane stopped coming to Nepal from India. Because Nepal is a landlocked nation, this route for fuel, medicine and other necessities is a literal lifeline. The blockade turned into another crisis on top of the others. But still we found a city surprisingly bustling with cars and trucks and taxis. Our friends there explained to us that, at that point, it was still possible to get all of the fuel you needed in the capital city…if you pay 2.5-5x the normal rates. And indeed, everyone we met seemed to have a blackmarket source of fuel–one friend’s source was actually a soldier. As our friend put it, “This crisis means that a few people are going to get very rich.” Another said of the fuel crisis and earthquake recovery, “The biggest crisis in Nepal is really the political one.”

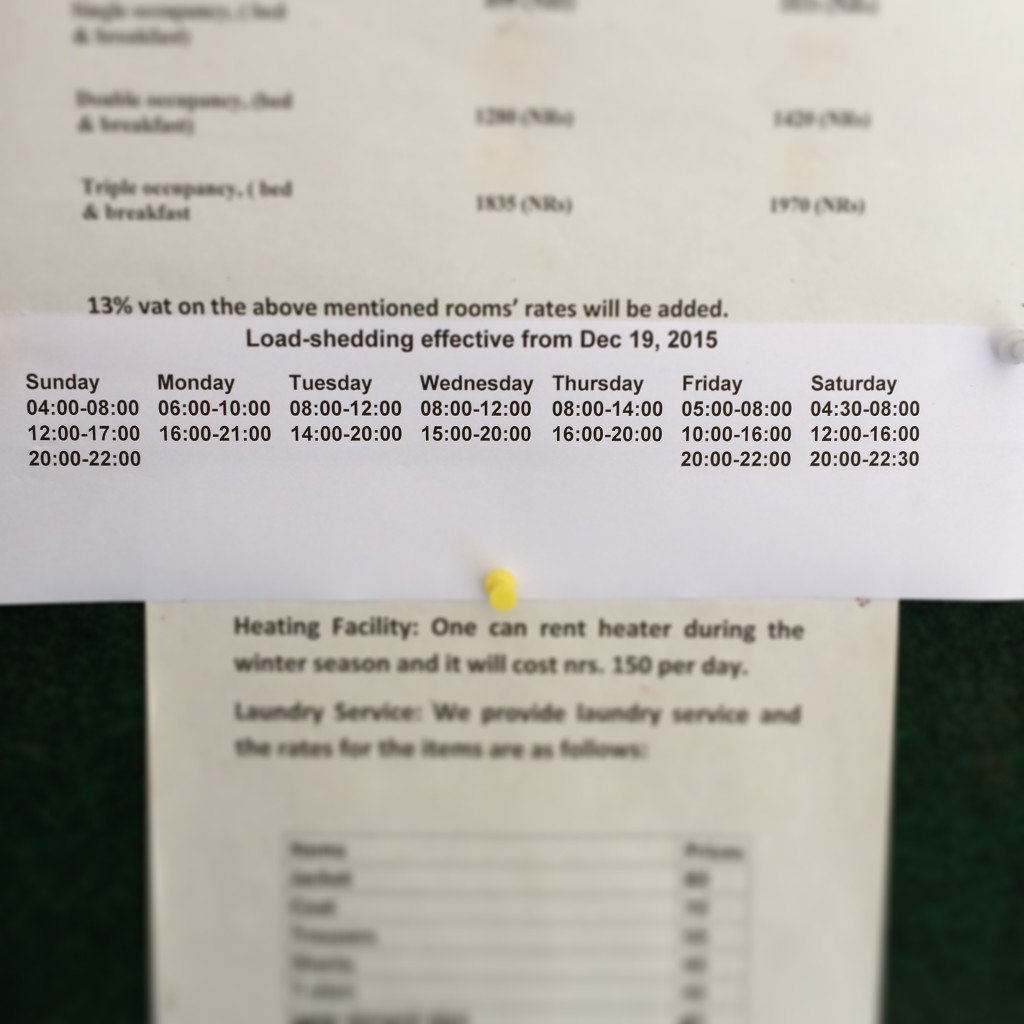

The fuel crisis was on top of a long-standing energy shortage. For decades, Kathmandu regularly has rolling blackouts called load-sheds, where each neighborhood goes without electricity for several hours a day because there isn’t enough for all of the population’s needs. By the time we left Kathmandu, load-shedding was up to 14 hours a day.

Despite all of these other crises, it was really a pollution crisis that was the most visible one to me. Many Nepalis wear masks to protect from breathing in the harmful particulates. You can actually see the soot and dust in the air. I had told my kids that Kathmandu was surrounded by hills the size of our mountains. But on most days, it was hard to make them out through the smog. Even an hour and a half outside of Kathmandu, you can no longer see the mountains on a clear winter’s day.

But to say that life in Nepal is horrible isn’t exactly right. There is still joy on the faces and in the voices of the Nepalis we met. And life does seem to go on despite the multiple and simultaneous crises.

There is an oft-said phrase in Nepali, ”Ke garne?” It means “What to do?” and is often used in an exasperated way. What to do about the corruption? What to do about the pollution? What to do about the earthquakes? Sometimes I find it frustrating to hear the resignation it implies.

But I heard it slightly differently a couple of times on this trip. I heard in it a tool for resiliency – the source of Nepal’s hardiness and beauty and joy. A way of getting past the horrible things that have befallen an incredible people and place. A call to adapt so that they may continue to live, laugh, and pray as they have done for centuries.