We Are All Disaster Philanthropists

Next Tuesday, I am scheduled to speak on a panel at the GEO conference on the subject of more effective disaster philanthropy. The session will be moderated by Debra Jacobs, president of the Patterson Foundation, and will include Molly de Aguiar of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. We’ll be talking about what donors learned from Superstorm […]

Next Tuesday, I am scheduled to speak on a panel at the GEO conference on the subject of more effective disaster philanthropy. The session will be moderated by Debra Jacobs, president of the Patterson Foundation, and will include Molly de Aguiar of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation.

We’ll be talking about what donors learned from Superstorm Sandy and what we can do better next time. On Wednesday, we are hosting an informal breakfast where we will share experiences about what other organizations did in previous disasters and learn more about what we can do to better prepare our communities for future disasters. If you are at the GEO Conference, I hope you will join us for one or both of these two sessions. In preparation for those conversations, here are some remarks I will be sharing next week.

The philanthropic response to Hurricane Sandy followed a pattern that frequently occurs with other big disasters. Sandy was a particularly well-suited subject for television news coverage — a slowly developing story, with plenty of spectacular pictures. It started with reports of a tropical depression in the Caribbean. As the storm slowly moved up the Atlantic coast, it received more broadcast time, replete with animated maps predicting the course of the storm based on different computer models.

When the storm made landfall in the United States, we witnessed the breathless weather reporter bravely standing in the wind and rain to report on the crashing waves. This exhilaration slowly evolved into the sad realities of death and destruction. It also brought a flood of contributions from compassionate donors wanting to help in some way.

It’s generally estimated that 90 percent of all donations flow in within the first 90 days after a disaster. No one knows exactly how much was donated for Sandy relief, but it easily topped many hundreds of millions. The American Red Cross alone reported that it had raised $300 million. The Robin Hood Relief Fund received nearly $75 million, mostly from a relief concert it promoted.

This outpouring of public support is gratifying in many ways. It meant that within a short period of time, most of the relief organizations raised much of the money they would need to cover emergency relief. The New York Attorney General reported that more than 80 Sandy-related funds were created.

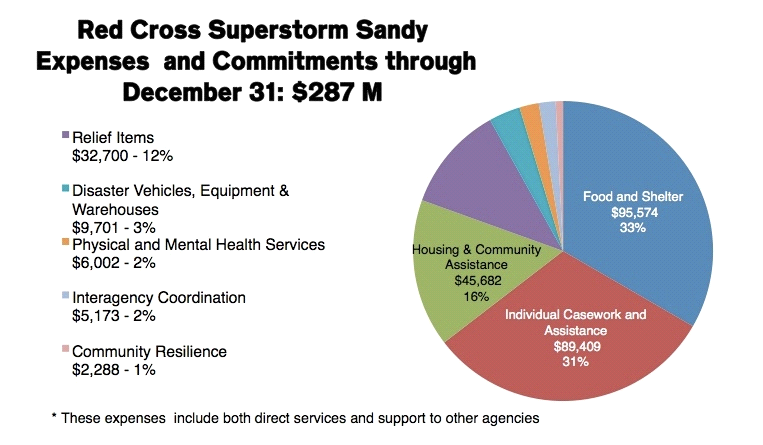

While this kind of windfall created excitement, it also caused an unanticipated dilemma: can a disaster generate too much money for relief or perhaps too much money too soon? The American Red Cross reported that as late as the summer of 2013, it had more than $100 million of the Sandy money raised still in reserve.

Prodded by the New York Attorney General and the public for not spending all of the money raised, the organization shifted its giving approach, and it now has become one of the largest re-granters of funds to mid-term rebuilding efforts.

A nonprofit executive in Moore, Oklahoma told me of a similar experience after the May tornadoes.

“We weren’t fund raising,” she said, “we were fund catching.”

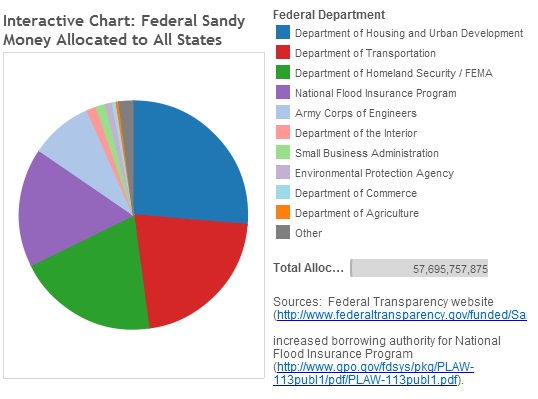

Meanwhile, the federal government was being urged to provide more mid- and long-term funding support. After a brief but intense political battle, Congress approved a grant of nearly $60 billion. According to the website NJ Spotlight, this included $9.7 billion in borrowing authority for the National Flood Insurance Program to pay out federal flood insurance claims and $48 billion that Congress allocated to the Disaster Relief Appropriations Act. The largest chunk of federal Sandy aid — some $15.2 billion — went to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) as Community Development Block Grants.

Given these huge sums of money — for both immediate and long-term relief — what is the unique role of private philanthropy? With all this money flowing, what can we do with our important — albeit limited — dollars?

Here at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, we pooled resources from 25 donors to focus on five best practices and unmet needs in our granting process for our CDP Hurricane Sandy Fund:

- Supporting media’s role in promoting awareness and engagement in recovery.

- Providing opportunities to support vulnerable immigrant populations.

- Supporting organizations providing mental health services.

- Promoting civic engagement of coastal communities in public policy issues.

- Supporting original research that uses Sandy as a model to forward-thinking about effective disaster response.

(At the Grantmakers for Effective Organizations National Conference next week in Los Angeles, I will be presenting on the topic “We are All Disaster Funders” with Debra Jacobs from The Patterson Foundation and Molly de Aguiar from the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation. We will explore the role that private philanthropy played in the response to Superstorm Sandy and lessons learned for funders of future disasters. Learn more.)