How a Wildfire Helped Address an Old Community Issue

Disasters often force us to deal with realities that we have long disregarded but suddenly can no longer ignore. Gatlinburg, Tennessee has long served as the gateway to the Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the United States. From its rustic beginnings, this little community has morphed into a booming, sprawling […]

Disasters often force us to deal with realities that we have long disregarded but suddenly can no longer ignore.

Gatlinburg, Tennessee has long served as the gateway to the Smoky Mountains National Park, the most visited national park in the United States. From its rustic beginnings, this little community has morphed into a booming, sprawling tourist destination, the third most important in the state’s economy.

On November 28, 2016 an unexceptional forest fire, fueled by 60 mile an hour winds, exploded into a wildfire that ultimately burned 17,000 acres, killed 14 people, and destroyed over two thousand homes and businesses.

Unlike other disasters, forest fires rarely leave unbroken swaths of destruction but hop and skip in unpredictable patterns. This fire caused unusual damage to a neighborhood with multiple-unit complexes housing nearly 75 percent of the tourist industry’s low wage workers and their families, many of them undocumented immigrants.

Another truism of disasters: They also reveal the most vulnerable in our communities—unseen right before our eyes. In this case, the essential workers necessary for the tourism industry to function were hit hard. So after years of ignoring the problem of a lack of affordable housing, it was a forest fire that made it impossible to ignore the issue any longer.

I traveled to Gatlinburg with my colleagues Regine Webster and Nancy Beers to learn about a recovery effort that has had many remarkable successes and meet with two community leaders, Alexandria Brownfield, CEO of Volunteer East Tennessee, and Bruce Bailey, Executive Director of AmeriCorps St. Louis (and a recent recipient of a Midwestern Early Recovery Fund grant).

I traveled to Gatlinburg with my colleagues Regine Webster and Nancy Beers to learn about a recovery effort that has had many remarkable successes and meet with two community leaders, Alexandria Brownfield, CEO of Volunteer East Tennessee, and Bruce Bailey, Executive Director of AmeriCorps St. Louis (and a recent recipient of a Midwestern Early Recovery Fund grant).

Here are a few things we learned:

-

- All disasters are local and ultimately resolved locally. Gatlinburg received plenty of outside help from organizations such as FEMA, the state, and many national nonprofit organizations. But it was local organizations, local government and local philanthropies, working with local people that ultimately made the difference and will do the heavy lifting over the long haul.

-

- Strong pre-existing social capital is vital. Although there was little disaster organization in place before the disaster – a blank slate, one person remarked – the community coalesced quickly around this disaster. Relationships among the major partners after the disaster were seamless because the relationships had been created well before the disaster struck.

-

- Collaboration among funders is essential. Trudy Hughes, Director of Regional Advancement for the East Tennessee Foundation, told us that within a few weeks the local funding community started meeting. They shared needs assessments, met with local leaders and volunteers, and ultimately shared funding strategies, promoting four different funds. Major funding came from the Dollywood Foundation, the private foundation of local legend Dolly Parton, contributing $9 million for individual needs. The foundation community also raised approximately $4 million, much of which was also distributed to individuals.

-

- Please send cash. The community received well over a million pounds of donated clothing, as well as donated products. Much of it now sadly sits in a warehouse, unusable for local needs. As in many disasters, donated products turned out to be a distraction and generally not helpful in meeting the needs of fire survivors.

-

- Volunteers can do tremendous things – if they know what to do. Within a week after the fire, a centralized volunteer recovery center had been created and soon there was a Mountain Tough Recovery Team website, well-organized assignments, and a response committee. One other critical factor is that the volunteer leaders worked closely with the county’s disaster manager, John Mathews, who was managing the local government response.

-

- Don’t wait to set up an unmet needs committee. The volunteer leaders started an unmet needs committee within weeks of the fire, relying on teams of volunteers and creative technology to gather information. As one person told me, “we became the early radar on just about everything.” Adding to its impact, it became the sole portal the entire community relied on for information.

- Coordinate the work of outside volunteers. With its strong start and excellent organization, the volunteer team also took on the assignment of coordinating the work of eager, but uninformed, outside volunteer organizations. As one leader told me, “we had rules about how to operate in our county on this disaster.”

Six months after the fire, reconstruction is evident everywhere. Private homes, where owners had insurance, are being rebuilt. Faith-based organizations such as the Appalachia Service Project have pledged to build 25 homes. The new Mountain Tough Recovery Team was launched with a mandate to rebuild homes and create rental units for service workers.

Today there is a sense of optimism in Gatlinburg. Devastated by a surprising and shocking forest fire, it is well on the way to solving some long neglected problems and building back better, bringing new economic vitality to the region.

More like this

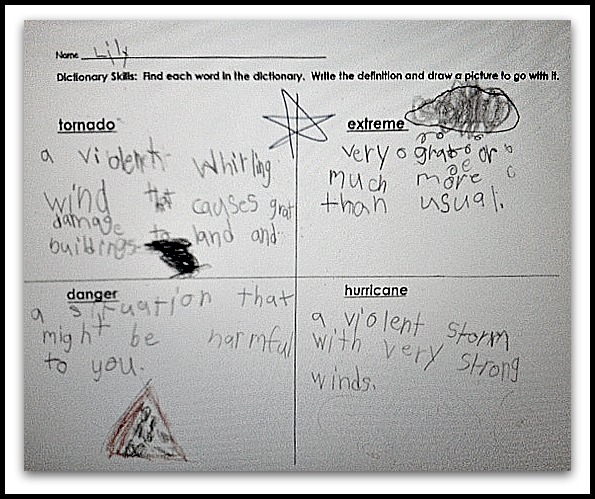

Extreme Weather Lessons Begin Early These Days