Learning from Japan’s Tsunami: Six Steps to Improve International Disaster Philanthropy

When news began trickling out about the massive earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan on March 11, 2011, it was immediately clear we were dealing with a disaster of historic proportions. What was less clear was how the rest of the world should respond, especially since the disaster hit a rich country rather than an […]

When news began trickling out about the massive earthquake and tsunami that struck Japan on March 11, 2011, it was immediately clear we were dealing with a disaster of historic proportions. What was less clear was how the rest of the world should respond, especially since the disaster hit a rich country rather than an impoverished one.

Ultimately, the US philanthropic response turned out to be far more generous than anybody anticipated. Americans donated roughly $750 million, the fifth highest total for any disaster in history and the greatest outpouring of US generosity for a disaster in another developed country. This made an enormous difference on the ground. However, a new report from the Japan Center for International Exchange finds that US donors and their Japanese partners faced many challenges, ones that are likely to become more commonplace in international disaster responses.

Ultimately, the US philanthropic response turned out to be far more generous than anybody anticipated. Americans donated roughly $750 million, the fifth highest total for any disaster in history and the greatest outpouring of US generosity for a disaster in another developed country. This made an enormous difference on the ground. However, a new report from the Japan Center for International Exchange finds that US donors and their Japanese partners faced many challenges, ones that are likely to become more commonplace in international disaster responses.

Drawing on the experiences of American and Japanese responders, the report recommends a number of steps that the philanthropic community can take to prepare for the next major overseas disaster, especially if it strikes another developed country.

1. Be aware of the full array of US responders.

The range of organizations involved in the Japan response extended far beyond the traditional humanitarian organizations and donors that come to mind when we think of disaster philanthropy. Thanks to the dense web of US-Japan ties, thousands of groups raised funds, and nearly 50 aggregated at least $1 million for giving programs in Japan. Most fell into one of three categories:

- professional humanitarian groups like Save the Children and World Vision;

- philanthropic intermediaries such as the United Way and GlobalGiving;

- and country-specific organizations such as Japan-America societies, US-Japan exchange organizations, and Japanese-American groups.

Yet those in one circle often had little awareness of what was happening with the others, so while some coordination took place within each circle this rarely extended across circles. For instance, although key players in the humanitarian world—humanitarian groups along with InterAction, USAID, and the US Chamber of Commerce—circulated information among themselves, there was little engagement with US-Japan organizations outside of the Washington Beltway and vice versa.

2. Build ties between responders in the United States and other developed countries.

It sometimes seemed that the same one or two humanitarian workers were the only Japanese in the Rolodexes of most American groups, and these individuals were quickly overwhelmed by inquiries from abroad. This underscored how crucial it is to nurture institutional ties between the US and overseas groups before disaster strikes, for example through strategic partnering on DRR initiatives and small-scale development projects in developing countries.

Similarly, the Japan response showed the benefits of channeling funds through local philanthropic intermediaries such as community foundations when dealing with developed-country disasters…and that there is a great need to support international networking among these groups.

3. Lay the groundwork for international donor coordination on developed-country disasters.

The Japan experience also suggests that modest efforts to fund networking among the umbrella organizations that facilitate emergency coordination—for instance, InterAction in the United States and Japan Platform and JANIC [Japanese NGO Center for International Cooperation]—could pay big dividends.

4. Create a clearinghouse of educational resources on international disaster philanthropy.

Many of the “Japan funds” were created by first-time grantmakers that scrambled to understand the basics of international philanthropy. This is likely to happen again. It is easy to envision US-German groups feeling compelled to raise funds for a large-scale tragedy in Munich and Korean-American organizations mobilizing if something happens in Seoul. It would help them enormously to be able to rely on an online resource center with basic information on what to consider before launching a disaster fund, legal requirements for overseas giving, and best practices for grantmaking.

5. Be more strategic in funding.

This means more money for recovery and less for immediate relief. Developed countries in particular usually have sufficient resources for immediate relief; the real need in Japan was funding for the nonprofit sector’s long-term recovery efforts.

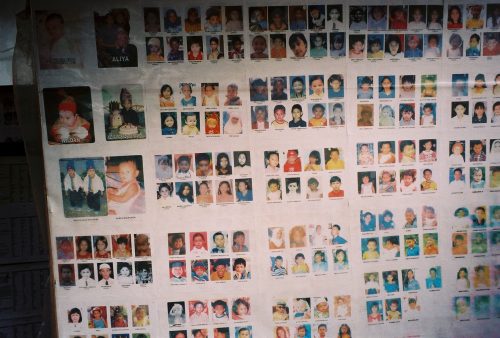

It also means relying less on sentimental appeal and more on hard data when allocating funds. If strategic-minded donors had known in real time that three times as much American money was going to programs targeting children as to those for the elderly—even though there were twice as many seniors as children in the disaster zone—perhaps they would have adjusted their approach.

6. Make applying easier.

Japanese grantseekers often found the application process for US funding challenging. Although efforts were made in summer 2011 to develop a uniform, short, and culturally appropriate application form to lighten the burden on grantseekers, it proved too daunting a task while responders were in crisis mode. Now that we are in “peacetime,” coalitions of US and overseas philanthropic organizations should revisit this question to prepare for the next disaster.

The full report, including further recommendations, is available online at Getting International Disaster Philanthropy Right: Lessons from Japan’s 2011 Tsunami.

More like this

2004 Tsunami +10 — Recovery, Lessons