What We Can Learn Today from Disaster Funding in 2018

This blog originally appeared on Candid’s website. So far, 2020 has been a record-setting year for disasters. There is, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic. Then there’s the Atlantic hurricane season, which has seen so much activity that forecasters exhausted the alphabetical list of storm names and had to move to using the Greek alphabet. This is only […]

This blog originally appeared on Candid’s website.

So far, 2020 has been a record-setting year for disasters. There is, of course, the COVID-19 pandemic. Then there’s the Atlantic hurricane season, which has seen so much activity that forecasters exhausted the alphabetical list of storm names and had to move to using the Greek alphabet. This is only the second time this has happened – and the hurricane season isn’t officially over until November 30. Wildfires have ravaged the U.S. West Coast. Not to mention the humanitarian crises in Yemen and Venezuela and the explosion in Beirut – one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history. The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) has created profiles on 17 disasters this year, an all-time high.

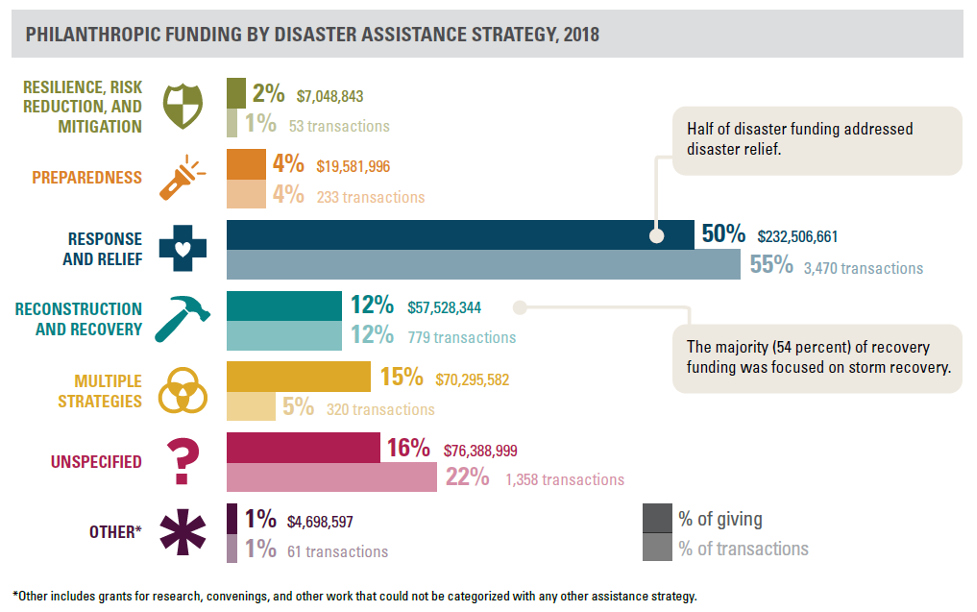

Against this backdrop, Candid and CDP released our annual Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy annual report last week. It examines the nearly $468 million foundations and public charities provided for disasters and humanitarian crises in 2018, the latest year for which we have comprehensive data. Some 50% of this amount was directed to response and relief. Only 12% of disaster grantmaking went toward reconstruction and recovery and 4% was for disaster preparedness. (Please see the end of this blog post for more about how we code grants for assistance strategies.)

These giving patterns are consistent with trends from previous years. Since 2014, when we published our first report, institutional donors have supported response and relief funding most heavily; this strategy has made up more than 40% of disaster-related giving in all years but one. By contrast, funding for preparedness has never exceeded 6% in any year and reconstruction and recovery funding has ranged from 5 to 17%.

We didn’t know, in 2018, that a global pandemic was on the horizon (though some have long been sounding the alarm). But many recognized that the number of costly disasters was rising and would require sustained and long-term interventions. Philanthropy can play a vital role in those interventions, helping communities better prepare for disasters and rebuild more effectively and equitably after disasters strike.

What did funding for disaster preparedness in 2018 look like? Who was funding mid- and long-term recovery? And what do we know about the impacts of 2018 funding in 2020?

Funders in 2018 that supported disaster preparedness and risk reduction

The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was the largest funder for disaster preparedness in 2018, with 45% of its disaster dollars addressing this strategy ($11.4 million). The foundation’s largest preparedness grant – one that is notably prescient – was $3 million to the World Health Organization to increase global preparedness for a pandemic and to support a Global Preparedness Monitoring Board to increase global accountability for preparedness efforts.

The Annenberg Foundation awarded $260,000 to the Los Angeles-based GRYD Foundation to help implement a mobile phone app built on the ShakeAlert Early Earthquake Warning System. Developed by public and private funds, the app provides crucial seconds of advance notice before an earthquake strikes. The app has been released and is in use today.

The Michigan-based Kresge Foundation awarded three grants to address flood risk management and resilience; two focused on Louisiana – a state that ranks second in the United States for the greatest proportion of properties with “substantial flood risk.” A $125,000 grant to the Center for Planning Excellence provided training and technical assistance to Louisiana communities at risk for flooding and a $90,000 award to the Lake Pontchartrain Basin Foundation addressed resilience by “employing multiple lines of defense against flood risk, with a focus on Eastern New Orleans and adjacent communities in St. Bernard Parish.”

Funders in 2018 that supported disaster recovery

Hurricane Harvey made landfall in August 2017 and has tied with Hurricane Katrina as the costliest U.S. tropical cyclone on record. Communities are still recovering to this day.

In 2018, Texas-based foundations demonstrated their support for the recovery effort. Many of the Houston Endowment’s recovery grants focused on covering the financial losses of art institutions. The Brown Foundation, a private foundation based in Houston, supported art organizations as well as other community-based nonprofits, including the YMCA of Greater Houston Area and the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation. The Greater Houston Community Foundation’s efforts included rebuilding homes and playgrounds and supporting fire departments to repair equipment and replenish supplies.

The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a large health-focused foundation, provided $1.7 million to the Texas Children’s Hospital to fund the Trauma and Grief Center to address children’s mental health needs in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey. The grant had three purposes: 1) to expand behavioral health services and school-based initiatives; 2) establish a law-enforcement training program to assist in identifying at-risk youth; and 3) create and disseminate evaluation tools for use by other communities in future disasters.

Recovery funding was not limited to Hurricane Harvey. The Michigan-based Charles Stewart Mott Foundation has consistently been committed to helping the city of Flint recover from the 2014 water crisis. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation supported recovery in Haiti from Hurricane Matthew (2016) and in Mexico from the 2017 earthquakes.

Why disaster funding in 2018 matters in 2020

The examples above highlight the efforts of some foundations to help communities prepare for and recover from disasters. It is often difficult, however, to ascertain the longer-term impact of a grant based on the short description that is available. In an effort to share lessons learned and demonstrate impact, CDP has published a series of case studies about its 2018 grantmaking – and how those grants have affected community responses to this year’s disasters.

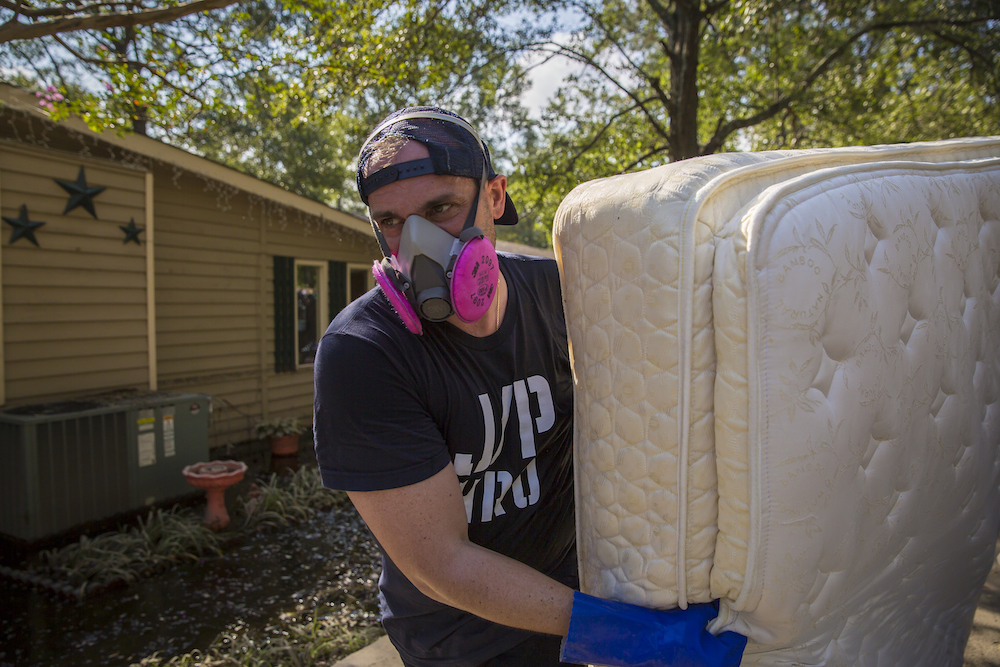

The Community Organized Relief Effort (CORE), formerly known as the J/P Haitian Relief Organization, has used its expertise in international response and recovery to support disaster response and preparedness in the U.S. with a social justice lens. In 2018, Hurricane Florence hit the Lumbee tribe in Robeson County, North Carolina, hard, and CORE was able to lend its unique expertise to partner with the tribe to retrofit buildings and prepare emergency evacuation plans. These measures came to good use in 2020 – when Tropical Storm Isaias hit the area, it caused far less damage. In addition, CORE’s relationships in Robeson County enabled it to fill a gap during the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, providing technical assistance for testing.

In 2018, the Camp Fire was the deadliest and most destructive wildfire in California history. CDP awarded a grant to the North Valley Community Foundation (NVCF) for additional staff support, trainings, counseling services and capacity building. Then, in 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the North Complex Fire hit the same community. This time, NVCF and the region were better prepared. With established relationships in place and with better-equipped staff, the foundation was able to move funding quickly at the beginning of the crisis with an eye toward what would be needed for long-term recovery, including addressing the community’s emotional and mental health needs.

Looking back at 2018 through the perspective of the numerous disasters and crises we’ve seen in 2020, it’s hard not to see the relevance and importance of disaster preparedness, recovery and resilience. Many of the communities affected by 2018 disasters still face a long road toward equitable recovery and preparedness for future disasters. The COVID-19 pandemic makes these efforts even more complex. Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy offers donors data to inform their future disaster giving and to maximize the impact of their giving.

To access the latest Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report, interactive dashboard and funding map, visit disasterphilanthropy.candid.org.

About the disaster taxonomy

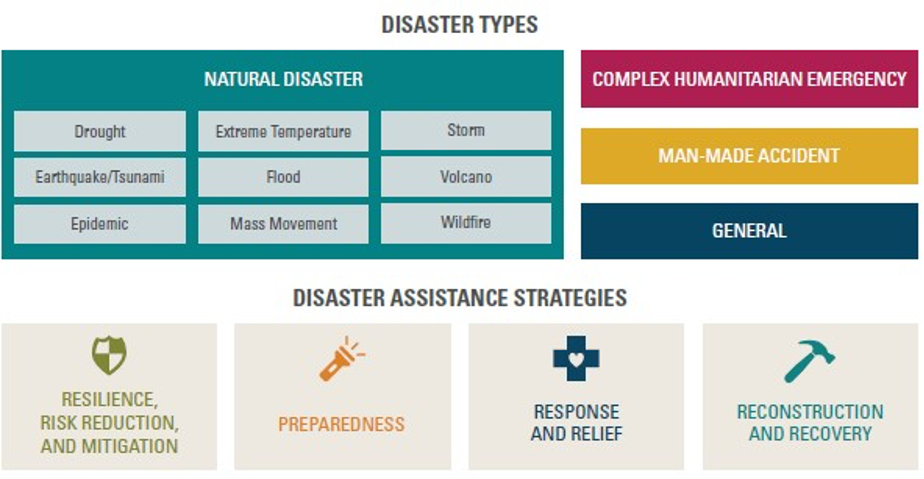

Candid codes grants in its database according to a custom disaster taxonomy, examining both the type of disaster addressed and the disaster assistance strategy implemented. Disaster assistance strategies are identified primarily based on the description provided by the grantmaker. If a grant is described as “disaster relief,” we will code that grant for response and relief. If no assistance strategy is described (for example, if the description says “disaster aid” or “hurricane support”) we will code the assistance strategy as unknown. We don’t make assumptions about the strategy implemented based on the timing of the grant. In a few cases, we may assign an assistance strategy based on what we know about the recipient organization’s mission. For example, First Response Team of America deploys rapid response teams that step in as soon as a disaster occurs, before other traditional relief organizations arrive. As such, if a grant to First Response Team of America doesn’t have a description, we still code the grant’s strategy as disaster response and relief.

Watch the recording of the “Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy 2020” webinar for a deeper dive into the findings and the philanthropic response to Hurricane Florence and Camp Fire.

More like this

Dramatic Increase in Giving in Response to Costliest Year of US Natural Disasters (2017)