Why Innovative WASH Funding Matters

As my plane landed in Kansas City on my way back from Nepal, I told the woman next to me that I would be glad to drink water from a tap and take an E.-coli-free shower. “I guess it’s the little things,” she said. Her comment got me thinking. Water isn’t a little thing. It’s […]

As my plane landed in Kansas City on my way back from Nepal, I told the woman next to me that I would be glad to drink water from a tap and take an E.-coli-free shower.

“I guess it’s the little things,” she said.

Her comment got me thinking. Water isn’t a little thing. It’s actually a very enormous thing that affects every disaster we’re involved with in a significant way. More than 1.1 billion people live without clean drinking water. At least 2.6 billion lack adequate sanitation. Every year, 1.8 billion people die from diarrheal diseases. More than 260 river basins are shared by at least two countries, mostly without legal or institutional arrangements, according to the World Water Council.

Here’s a run down of the big role water plays in some of our current funding areas:

Global Refugee Crisis

The Global Refugee Crisis that has dominated humanitarian response provides a complex situation for water as well. Inside Syria, warring parties have interrupted water supply to civilians—UNICEF recorded at least eighteen deliberate water cuts in 2015. Bombings have damaged the infrastructure that carries water to homes in many parts, and community taps built by nongovernmental groups in recent years are the supply lines that have been targeted in the continuing conflict. The unpredictability of war makes the process of going to collect water dangerous and sometimes deadly, and municipal workers are often unable to carry out necessary repairs. In addition, power cuts make it difficult for water to be pumped through what supply lines are available. The consequences of dirty water—diarrhea, typhoid, hepatitis and other diseases, are more severe inside Syria as well, where access to medical care is often minimal, or dangerous.

Refugees throughout the Syria region do not usually have access to clean water. Most formal camps cannot support the basic standards of water supply, and many of the countries surrounding Syria are in water-scare situations already. Jordan, for example, is one of the ten most water-scare countries in the world. In some areas, the water supply per refugee is about thirty liters per day, or one-tenth of what the average American uses.

Nepal Earthquakes

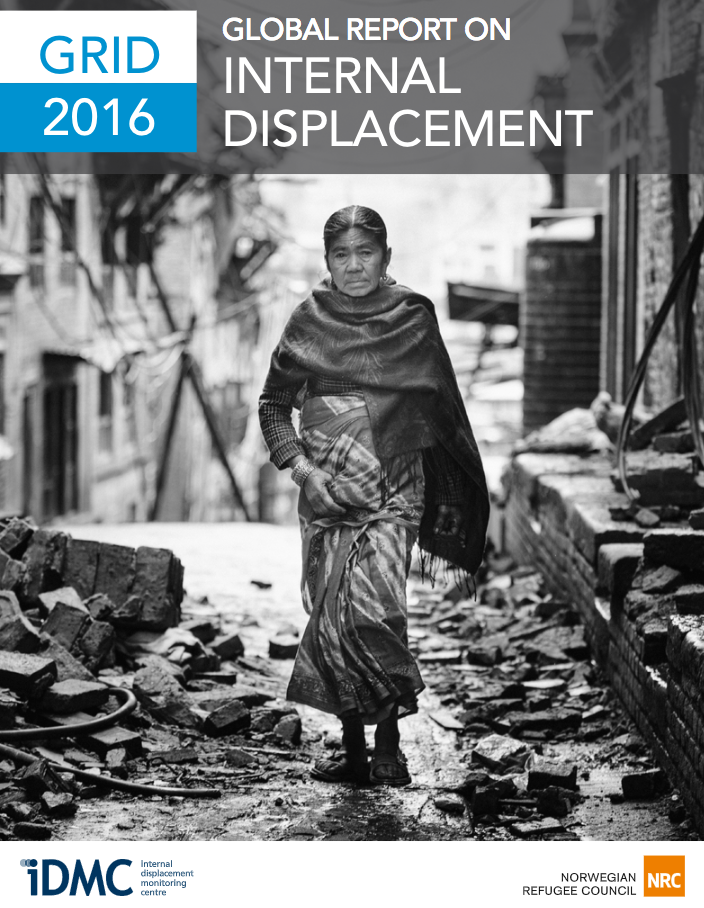

Even before the 2015 Nepal Earthquakes, water sanitation was a central health issue in Nepal. About thirty percent of the 28 million residents are below the poverty line, with low access to safe drinking water and sanitation facilities. In many villages, people still draw water from unprotected sources, such as rivers, streams, and unprotected springs, or have to walk long distances and wait in line at tap stands. Insufficient water supply creates poor hygiene practices. The use of soap and soap alternatives is infrequent and open defecation, especially in rural villages, is common. These factors, combined with monsoons and high temperatures, cause high levels of preventable disease and death.

Ebola Virus and Liberia

In Liberia, Sierra Leone, Guinea, and other countries, the Ebola virus crisis followed upon several decades of civil conflict. Monrovia, the capitol of Liberia, even lacks electricity and running water. So in a country where about thirty percent do not have clean drinking water and four million are with out sanitation items, addressing a virus such as Ebola was nearly impossible. (Imagine being a health worker, sweating out about three liters an hour underneath the protective suit while working with patients!)

Developing Water Crisis

In areas of Somalia and Ethiopia, a strong El Niño weather pattern is driving the worst drought in fifty years. In some situations, as natural sources have dried up, people have to walk six hours to collect water. A huge part of Ethiopia’s population is dependent on rain-fed agriculture for food and income, and the lack of water and food has already caused many children to drop out of school in order to search for resources to survive.

Three Ways Funders Can Help

Disaster philanthropy can reverse the trend of the global water crisis through innovative water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) efforts. Though often complex and large, WASH projects are one of the most important investments funders can make in a community. For every $1 invested in WASH projects, the World Health Organization estimates a $5 to $28 return in increased productivity and decreased healthcare costs.

Here are three strategies to get more from your investment in WASH efforts:

- Place the focus on community. Communities should be involved in planning, maintaining, and sustaining the project, as well as using it. This means complementary programs focused on advocacy and education around hygiene, job skills training, and civic capacity building that allow a water project to continue to be useful for many years.

- Partner with other funders and foster collaboration between companies and NGOs, between different NGOs, between government organizations and social entrepreneurs. Take the time to reach out and develop collaborative WASH partnerships for greater, more effective results.

- Be creative. I urge funders to do this more than anything else. Be creative! Be bold! Do the thing that has yet to be dreamed up. Do the unthinkable. It just might change the world.

Water isn’t a little thing. It is a vital and yet limited resource that must be protected to meet the world’s increasing demands. Innovative WASH efforts are not only possible, but essential for the survival of billions.

More like this

Three Images That Stick With Me From 2015