2017 Disasters Could Prompt Reconsideration of FEMA’s Role with States

Last year, the U.S. experienced a record-breaking number of natural disasters causing an unprecedented amount of damage, well over $300 billion. This resulted in challenges for Congress and the Trump Administration regarding how to pay for clean-up and rebuilding. One of the problems has been around for a while. The long bankrupt (more than $16 […]

Last year, the U.S. experienced a record-breaking number of natural disasters causing an unprecedented amount of damage, well over $300 billion. This resulted in challenges for Congress and the Trump Administration regarding how to pay for clean-up and rebuilding.

One of the problems has been around for a while. The long bankrupt (more than $16 billion) National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is currently working off of an extension that is scheduled to run out July 31 – right in the middle of hurricane season. Last week, the House of Representative passed legislation to extend the program through the end of November. If the Senate does not reauthorize NFIP, or better yet solve some of the program’s longstanding problems, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) will be unable to provide new flood insurance contracts to those that expire and FEMA’s authority to borrow will be significantly reduced. But this is a can that has been kicked down the road before: Congress has extended or allowed NFIP to lapse for a short period more than 20 times since 2010, without making significant changes to the program.

The 2017 disasters brought some other funding challenges to the federal government as well. According to the Wharton Risk Management and Decision Processes Center, Congress passed two supplemental spending bills last fall appropriating $34.5 billion in post-disaster funds and forgiving NFIP’s $16 billion of debt. In early 2018, Congress approved a two-year budget that included an additional $90 billion for disaster rebuilding. This puts the total spending in response to the 2017 events at over $130 billion—another record. According to Bloomberg news, the federal government has spent $357 billion on disaster recovery over the past decade. Meanwhile, the U.S. Government Accountability Office, the independent agency that advises Congress, ranks climate change as one of the greatest financial risks facing the federal government, largely due to the increase the cost as severe weather events become more common and intense due to climate change.

FEMA Administrator Brock Long has started sounding the message that change needs to come to how the US funds disaster work. In an interview after Hurricane Harvey, Long said that state representatives, state legislative officials and local elected officials need to listen up. He stressed that Harvey should be a wake-up call for state and local officials to give governors and emergency management directors the resources that they need to be fully staffed, to design rainy day funds, and to have standalone individual assistance and public assistance programs.

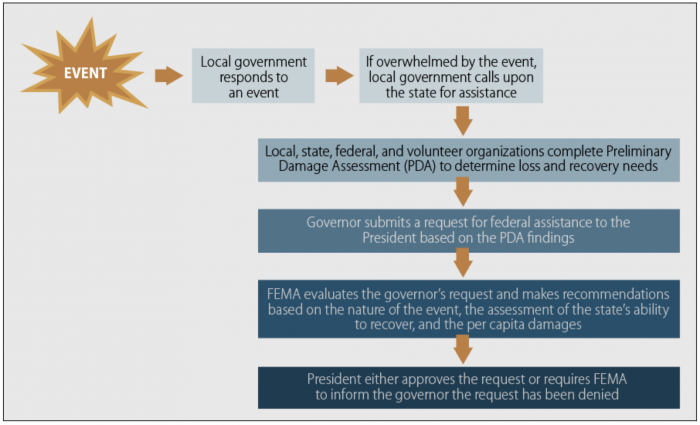

Source: Congressional Research Service

FEMA is looking for ways to slow down federal costs by having states, cities and homeowners bear more of the costs, with less of the risk falling on the federal government. In early 2017, the FEMA Reauthorization Act was reintroduced in the U.S. House of Representatives with a provision requiring a comprehensive study of and recommendations for cutting costs across all levels of government. Some ideas under consideration include stopping payments for homes that keep flooding and raising the threshold for triggering federal public assistance after a disaster. Before he left office, former FEMA chief Craig Fugate suggested imposing a state disaster deductible, which would require states to pay a larger share of disaster recovery costs up front. As a condition of receiving federal funds, states would pay a deductible toward recovery costs for certain types of assistance. Additionally, states would be able to earn credits toward their deductible by investing in activities that save lives, mitigate risks and reduce disaster costs.

Some of these changes could be made with the upcoming NFIP reauthorization. Even without legislation, FEMA says it could shift the initial costs for disaster relief to local or state governments.

It is understandable that the federal government would want to transfer more of the costs to states. All 50 states and the District of Columbia, between 2005 and 2014, experienced disasters severe enough to trigger a federal emergency or major disaster declaration, including floods, hurricanes, wildfires and blizzards. Wyoming had the fewest, with just three declarations, and Oklahoma — in the heart of tornado alley — topped the list at 36.

But are states ready to take on more of the disaster relief burden? A recent report released by the Pew Charitable Trusts concludes it is too early to tell, but not likely. In the admirable, comprehensive research project, What We Don’t Know About State Spending on Natural Disasters Could Cost Us, Pew found that most states don’t really know how much they are spending on natural disasters and don’t comprehensively track disaster spending. Furthermore, state spending is highly variable, with costs, levels of municipal cooperation and pre-disaster programs varying widely.

Pew concluded that, “in an era of increasingly expensive disasters, efforts to adjust the funding relationship among the federal, state, and local levels and manage growing costs through mitigation are likely to increase. However, Pew’s research shows that states are not comprehensively tracking their disaster spending. The limited available state data strongly indicate that these expenditures vary widely across states. Without complete data about state investments and local cost-sharing practices, any proposal tackling intergovernmental spending issues or cost reduction will be operating largely in the dark.”

So far this year there have already been six natural disasters that have caused $1 billion or more in damage. It’s clear that an overhaul of federal disaster policies that puts more emphasis on preparation and mitigation is long overdue. Foundations and corporations can encourage this effort through thoughtful strategic disaster philanthropy to support state and local efforts. In the meantime, we’ll be watching carefully as Congress and FEMA begin to explore new approaches to responding to disasters.

More like this

What the Government Shutdown Really Means to Disasters