Remittances

Remittances are the transfer of money by a person in one country to a person in another country, often used by migrant workers to send money to family who remain in their home country.

Overview

Remittances are the transfer of funds from one person to another.

Often, this refers to using international remittances to send money from one person to family members who remain in their home country. Remittances are often a household income-generation strategy, with one (or more) people agreeing to seek employment outside the family’s community (including rural-to-urban migration in-country) or moving to another country.

More than 280 million people (including 32.5 million refugees) live outside their birth country. This equals 3.6% of the world’s population. Many other people are descendants of immigrants and refugees who have retained strong ties to their families in their home countries.

Remittances are primarily used to provide for basic household needs, with three-quarters covering essentials such as food, school fees, housing costs and medical expenses. The remaining 25% is usually invested in entrepreneurship (including agriculture) or savings.

Role of remittances

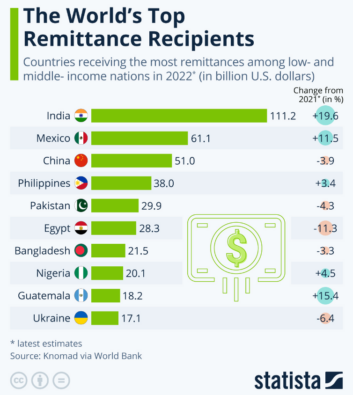

Remittances play a very important role in many countries, making up almost 4% of the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in over 70 countries. For example, remittances made up 27.3% of the GDP in Somalia in 2021 and 2022. In Yemen, at least one in ten people rely on remittances for basic living expenses. In 2019, remittances in Yemen totaled $3.8 billion (13% of GDP).

Although most countries that top the list of remittance recipients are low-to-moderate-income countries, France is in the top seven. In 2021, France received more remittances ($32 billion) than it sent out ($25.7 billion). In 2022, the incoming remittances dropped to about $28 billion.

The United Nations says remittances contribute three times more capital to still-developing countries than international aid (official development assistance and foreign direct investment combined). In 2018, $529 billion of the $689 billion sent home by migrant workers went to developing countries.

Internal or domestic remittances

While most information and monitoring of remittances occurs in the international setting, there are also ‘internal remittances’ (also called domestic remittances) from family members who have left home, but not the country. Most commonly, this occurs between rural and urban communities.

There is a lack of information and research about domestic remittances. They are not officially tracked, but research from 2009 showed that there tend to be more of them, although the transfer amounts are smaller.

A 2019 study of the influence of remittances on domestic tourism found that significantly more households in Mexico received domestic remittances than international remittances. A 2016 study on domestic remittances in South Africa found that they involved two-thirds of adults and totaled “between $11 billion and $13 billion, equivalent to 4 percent of GDP.” Internal remittances increase household spending on food, health and education. The use of internal remittances also increases the use of banking services.

Remittances and disasters

In addition to providing capital to some of the poorest people in the world, remittances can make a significant difference in the lives of people affected by disasters. Migrant workers may send more money home when there is a family emergency or a loss of crops. The money can serve as immediate and direct aid to families affected by disasters, helping to bridge the gap between the occurrence of the disaster and the arrival of official aid.

A research study published in 2018 looked at 18 major disasters over 14 years. It found that while remittances initially spike after a disaster, the amount of money transferred over the entire year did not change significantly. Share on X

While migrants were able to send more money at a crucial time, they were unable to increase the amount of money sent for the year because their own overall financial position did not change, instead, the immediate increase is compensated by a later decrease. Additionally, while they did provide immediate support after the crisis, there were no ongoing support increases to provide short- or long-term disaster recovery assistance.

Challenges in sending remittances

Migrant workers who send money home may be employed in minimum-wage jobs or jobs that do not pay a livable wage. This can significantly reduce the amount of money available for a person to use for remittances. Migrants with certain employment visas and second-generation immigrants may have higher incomes and may not face the same challenges.

Remittances are also affected by economic sanctions placed by one government against another or bank de-risking. Economic downturns, pandemics, and war or conflict also create challenges for remittances. For example, in Yemen, Oxfam reported that at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, “remittances drop[ed] by as much as 80 percent between January and April … as Yemenis working in Gulf states, the UK and the US saw their incomes plummet due to lockdowns and social distancing.”

Costs of transfers

One of the biggest challenges for those sending and receiving remittances is the relatively high cost of processing these transactions through banks and money services. Companies such as Western Union, MoneyGram and Xoom (part of PayPal) can charge significant fees. Using mobile transfers can decrease the cost, but in 2022, digital transfers accounted for only 3.5% of funds sent.

The 2023 average 6.24% fee either adds additional costs for the individual sending money or reduces the amount they can send. The World Bank estimates that reducing this cost by 5% could save senders $16 billion a year.

Additionally, because of national and international laws regarding money laundering and the financing of terrorism, the safest ways of transferring money can also be the most expensive. The World Bank cites banks as the most expensive, with an average fee of 11.84%, followed by national postal services at 6.31%. While new technology companies are helping reduce the cost of remittances, many people still resort to less secure methods, such as mailing cash or relying on travelers to carry the remittance to the destination.

A popular way of transferring funds from individuals – Hawala – is also illegal in most countries, including the U.S. Meaning trust or transfer, Hawala dates back to the 8th century and provides an informal system to transfer funds from one person to another, using hawaladars – third-party individuals who agree to receive or deliver funds. It exists outside formal banking systems and is grounded on trust, as no money exchanges hands between the hawaladars in each country. It is cheaper and faster than typical banking methods. As of 2020, Dow Jones reported that about $332.6 billion moves each year through Hawala channels.

Key Facts

- Remittances help support approximately 11% of the global population. One billion people worldwide take part in remittances as either a sender or recipient. Share on X About 800 million people (1 in 9) are recipients of money from 200 million family members who migrated to one of 40 countries to find work.

- Remittances are increasing. In June 2023, the World Bank estimated that remittances would likely grow by “1.4% to $656 billion in 2023 as economic activity in remittance source countries is set to soften, limiting employment and wage gains for migrants.” In 2022 there was 8% growth, totaling $647 billion.

- Most of the income earned by people who send remittances remains in the country where they now live. On average, only 15% of a person’s earnings are sent as remittances. The average worker sends about $200-300 U.S. every month or every other month.

- About half of the money sent through remittances goes to rural communities. Approximately 75-80% of the world’s poor and food-insecure populations live in rural areas. Remittances allow for improved agricultural activities and education attainment.

- Since 2018, the International Day of Family Remittances has been celebrated on June 16. It recognizes the importance of remittances.

- Much of the money sent as remittances is sent through unofficial channels – such as hawala. This means it is difficult to track, so the amount of money sent as remittances could be much higher.

- Remittances are not a substitute for employment or development aid. Only one in three households in Tajikistan (the world’s most remittance-dependent country) have a family member working in another country. Families receiving remittances tend not to be the poorest of the poor because those families cannot afford to send a family member overseas due to the high migration costs.

How to Help

- Invest in technology to lower transfer costs and sustainable infrastructure for money transfers. When it costs less to transfer money, people can send higher amounts. Receiving remittances through safer, official channels requires access to banks and reputable money transfer agencies. Sustainable infrastructure and transit will give more people easier access to these official agencies to receive remittances.

- Support financial literacy training and bank access. It is important to provide education about access to banking services, savings and other financial literacy tools. In 2021, the Global Fund for Community Foundations gave a $65,880 grant to the Zambia Governance Foundation to promote community financial asset building through financial literacy, mentoring for small businesses and creating community funds.

- Invest in small businesses and agricultural development. International remittances are often used for agricultural business development, particularly in rural communities, and supportive programming can enhance that work. According to the World Bank, growth in the agriculture sector is two to four times more effective in raising incomes among the poorest compared to other sectors. In 2021, Comic Relief provided a $255,235 grant to Good Nature Agro in Zambia to improve access to financial services and strengthen the resilience of 9,500 farmers in rural Zambia.

- Support better tracking of how remittances travel across the globe. There are significant challenges to tracking remittances, including the use of informal and unofficial methods of transferring money. Some countries may also over-report remittances for various reasons, including poor data collection. Domestic remittances are rarely tracked, and little is known about their impact on recipients.

- Support organizations and activities that focus on equitable aid distribution. People who receive remittances may not be the only ones who need help or are the most in need. The aid supplied by funders and government is key to making sure support is equitable for everyone in an affected area.

What Funders Are Doing

- Beginning in March 2022, and still in operation as of July 2023, Western Union waived its fees on any money being sent from a bank account for payout onto a card or bank account in Ukraine. They also have allowed money transfers sent to neighboring countries such as Hungary, Poland, Slovakia, Moldova and Romania to be paid out in cash, facilitating access to funds for migrants from Ukraine.

- The Rockefeller Foundation gave a $249,728 grant in 2015 to the Institute for Social and Environmental Transition’s work in Nepal. The group used the grant to support a rebuilding approach, using remittance flows as a lever to create a lasting resilience dividend.

- In 2016, the MoneyGram International Corporate Giving Program waived all transaction fees for monetary transfers from the U.S. and South America to Ecuador and donations to the American Red Cross following the earthquake.

Learn More

- CDP Disaster Philanthropy Playbook Strategy: Disaster Relief

- CDP Issue Insight: Disaster Phases

- Pew Research: Remittances

- International Fund for Agricultural Development: International Day of Family Remittances

- Migration Data Portal: Remittances

- IOM: World Migration Report

- Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD): Remittances Data

- The World Bank: Migration and Remittances Brief

- Monito.com

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.