The Complicated Web of Disaster Funding and What You Can Do About It

Why does CDP emphasize that philanthropic support for disaster activities needs to be strategic? The answer is simple: there isn’t very much of it, relative to the need, and it is absolutely essential. Total disaster funding is a complicated web—a “mosaic”—with many different funding sources, each with their own set of rules, regulations, timelines, and […]

Why does CDP emphasize that philanthropic support for disaster activities needs to be strategic? The answer is simple: there isn’t very much of it, relative to the need, and it is absolutely essential.

Total disaster funding is a complicated web—a “mosaic”—with many different funding sources, each with their own set of rules, regulations, timelines, and purposes. Sources not only include philanthropic cash contributions, but also funding from insurance policies, corporate in-kind donations, state sources, and most-of-all, the federal government. In many situations, philanthropic support may be the smallest source, but it has many (potentially) valuable attributes: it is relatively flexible, can take risks, moves quickly, and yet focuses on the long view. It is small in comparison but often one of the few sources available.

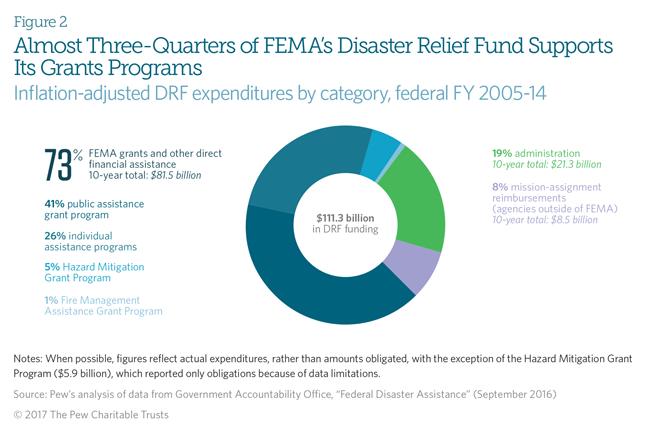

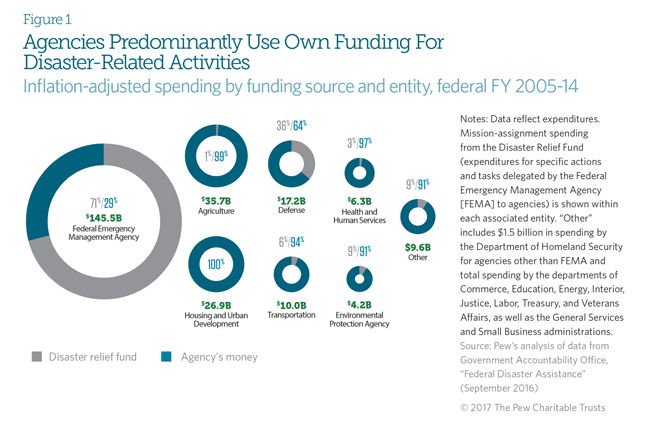

For the years 2005-2014 (that includes Katrina and Sandy, but not the recent 2017 disasters), the federal out-lay for disasters totaled an amazing $255 billion. But according to a Pew Charitable Trusts report, only about 44 percent of federal support went to FEMA’s Disaster Relief Fund (DRF). FEMA uses most of this money for three major programs that should be familiar to anyone involved in disasters:

- Public assistance grants to state and local governments to repair and replace public infrastructure;

- Individual assistance grants for essential home repairs, temporary housing costs, and other necessary expenses such as counseling; and

- Hazard mitigation grant programs, usually provided after the disaster for reducing future disaster losses through mitigation measures such as property buyouts and home elevations.

A small portion of the FEMA money goes to 17 other federal agencies to help support their disaster-related work. This becomes an important source of funding post-disaster, particularly for big projects such as housing and infrastructure.

However, according to the Pew research, the majority of the $146 billion spent by federal agencies on disasters, came from their own budgets and not through FEMA. To put it another way, congressional appropriations for disasters support FEMA along with 17 other federal agencies. Much of the funding is for repairing and rebuilding public facilities and infrastructure. Disasters adversely affect public sector infrastructure too, something that is easy to forget when the TV coverage is focused on homeowners and businesses.

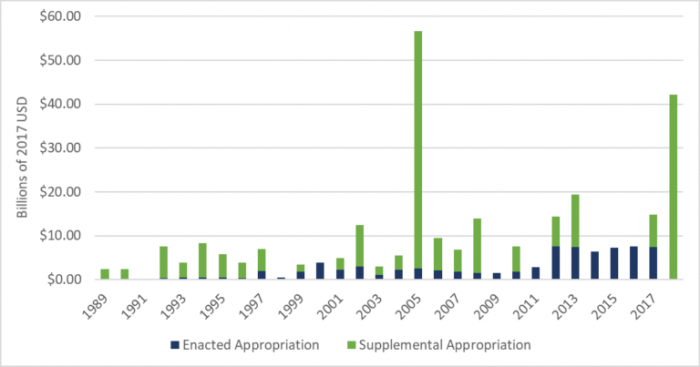

Another study, this from the Wharton School Risk Management and Process Center, looked at the special funding that Congress has passed with increasing frequency to supplement disaster funding. In 2017, Congress passed two supplemental spending bills appropriating $34.5 billion in post-disaster funds and forgiving $16 billion of debt for the National Flood Insurance Program. Later, Congress approved a two-year budget that included an additional $90 billion for disaster rebuilding. This puts the total spending in response to the 2017 disasters so far at over $130 billion—another record.

Funding to the FEMA DRF by fiscal year is shown in the figure below. As seen in the figure, annual appropriations routinely fall far below the money FEMA spends on disaster response.

What can foundations and corporations do?

- Invest intentionally, not reactively. Disaster-related funding is complicated and it’s important to know the facts before you act. You need to be aware of government appropriations before you decide how to use your scarce funds. Your dollars could be the most important ones of all – doing things no one else can do.

- Learn more about what government does and doesn’t fund. The federal government’s role in disaster work is huge. But as special appropriations increase, it is becoming more controversial. It is worth taking the time to educate yourself and other decision makers on the best approaches for the future.

- Fill the gaps left by lengthy government funding processes. Currently most federal dollars are for long-term rebuilding. As the Wharton report observes: “Consider that the $90 billion in disaster funding was appropriated roughly six months after the events. By the time that funding works its way from Treasury, to the agencies, to the state and local governments, and, if applicable, to residents or businesses, it can be months or years after the disaster.”

- Look for opportunities to support pre-disaster funds. FEMA in particular is beginning to pay more attention to risk reduction and mitigation. Currently the federal government allocates nearly 90 percent of its risk reduction dollars post-disaster, tied to a Presidential disaster declaration, and spending little ahead of time. But this is likely to change and might provide new opportunities for partnerships with the philanthropic sector.

More like this

2017 Disasters Could Prompt Reconsideration of FEMA’s Role with States