Why Us? Managing Uncertainty in a Disaster-Prone Area

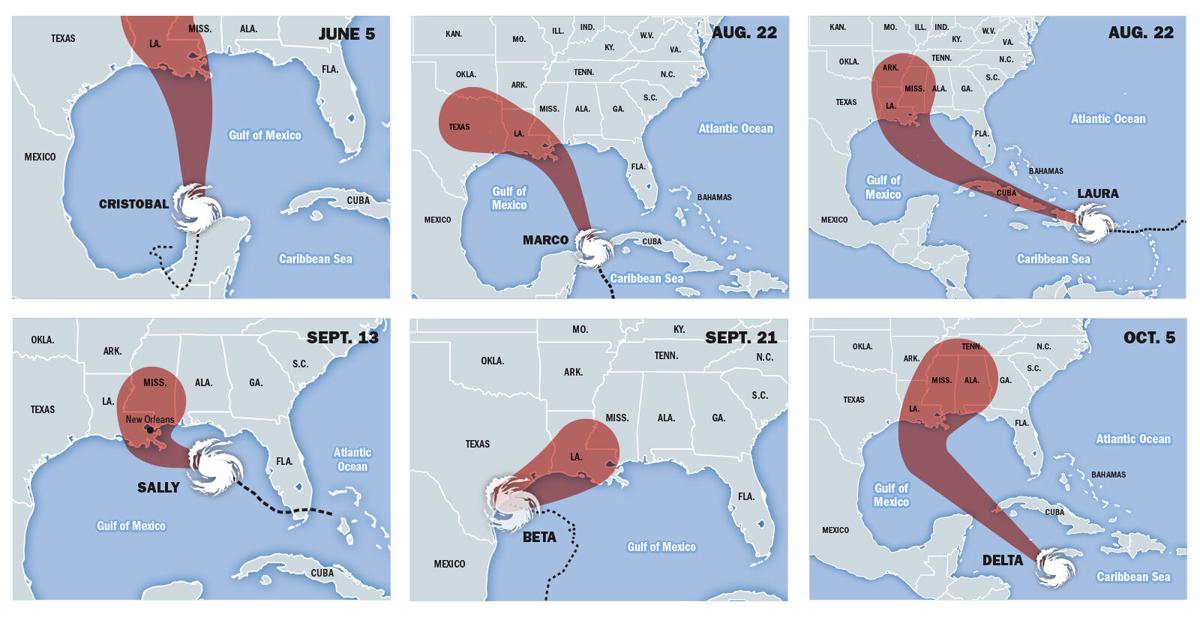

I am a self-described “disaster junkie,” but even I am growing weary of being in the path of hurricanes. Of the eight Gulf storms this year, six have taken direct aim at Louisiana. Beginning with Cristobal on June 6, Louisiana has been threatened by Marco (Aug. 22), Laura (Aug. 22), Sally (Sept. 13), Beta (Sept. […]

I am a self-described “disaster junkie,” but even I am growing weary of being in the path of hurricanes.

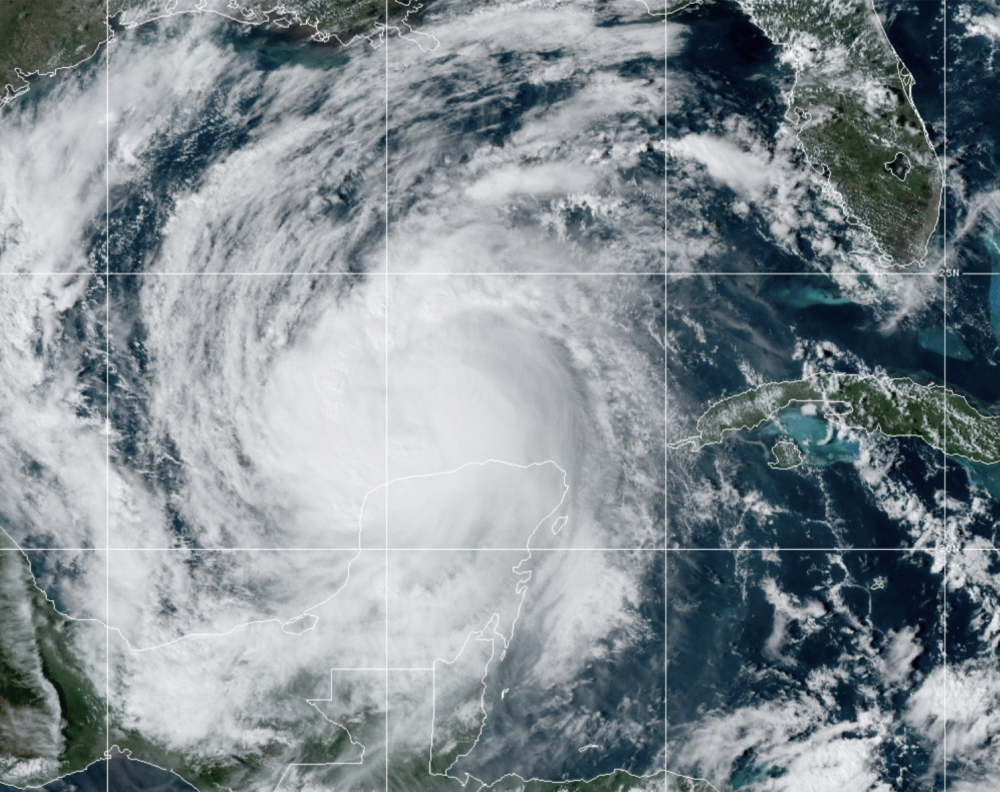

Of the eight Gulf storms this year, six have taken direct aim at Louisiana. Beginning with Cristobal on June 6, Louisiana has been threatened by Marco (Aug. 22), Laura (Aug. 22), Sally (Sept. 13), Beta (Sept. 21) and now Delta, currently a Category 2 hurricane expected to make landfall in Louisiana this weekend. Of the prior five, only Laura did any substantial damage to the state.

However, thousands of people are still evacuated, including many staying in hotels in my city, New Orleans. Others are living in their unrepaired homes in the affected area, many without running water or power.

Fatigue around hurricanes is a real thing, especially this year. One friend, half-jokingly said, “I’ll probably just stand outside and hope for debris or rising waters to put me out of my misery at this point.” And indeed, the consensus among my friends is a mix of “why us” and “I don’t even care anymore,” along with a sarcastic (I hope!) “Wheeee.” It’s the latter thought that is dangerous. As another friend reminded me, disaster fatigue is what got people killed during Katrina in 2005.

Apathy to the danger of disasters is a serious issue and something funders need to pay attention to. We often talk at the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) about the impact that multiple disasters – within the same year or cyclical disasters occurring year in and out – have on the funding community. But we don’t always look at what happens within a community that repeatedly faces disaster threats in the span of a few months, especially during a pandemic.

We Louisianans are a proud and resourceful people, but as a state overall, we are also very poor. Data released last year from the Census Bureau showed that Louisiana had the third-highest poverty rate in the country. While the U.S. average in 2018 places 11.8% of people below the poverty line, it is 18.6% in Louisiana. And for children, it’s even higher: one in four of our kids live in poverty. These statistics are from before COVID-19 hit; tens of thousands of people in the state have since lost their jobs. Many Louisianans rely on tourism, the oil and gas industry, or the fishing economy. During a hurricane or in the lead-up to one, none of those are viable activities.

Many living in low-lying areas of the state have already been asked to evacuate multiple times this year. Often that means staying with friends and family, but with COVID-19, that isn’t always possible. Hotel bills add up, and so does the cost of traveling back and forth. Even those of us living away from the coast are not 100% safe. I live eight feet below sea level. Although my house is slightly raised and unlikely to flood, I rely on a series of levees and canals to prevent that from happening. Even in a typical thunderstorm, localized street flooding and a loss of power or a need to boil water are constant threats. So we cook the contents of the freezer and stock up on water and gas.

And we did that in June. And August. And September. And we’ll be doing it again this week.

Funders can help make life easier in disaster-prone areas by investing in preparedness and mitigation strategies. Here are a few ideas:

- Address the root causes of poverty to help improve someone’s circumstances before a storm.

- Develop and support emergency savings and loan programs for people living in poverty.

- Give nonprofits support so they can help assist people in need of evacuation.

- Provide education and support for stormwater management to help low-lying areas understand how and why to better manage large influxes of water.

- Advocate for government investments in equitable mitigation policies and practices such as levee construction and maintenance, land use (especially for new residential development), use of permeable pavement and increasing green spaces.

- Invest directly in climate change and risk reduction strategies whenever possible.

Delta will likely be a Category 2 storm when it makes landfall, and it poses a real threat to Gulf Coast residents.

If Delta stays on its current track, it will impact communities that have been repeatedly affected by hurricanes and flooding, including the Great Flood of 2016. New Orleans will bear the brunt of the rain and winds, putting a real test to the city’s levee system.

If it shifts west of its current track, it will re-impact the areas still recovering from Hurricane Laura. Thousands of evacuees remain in New Orleans and many of the damaged homes are have not been tarped, let along fully protected from the elements.

And if Delta moves east, it impacts our neighbors in Mississippi, who tops the nation’s poverty rate list.

The best-case scenario, however unlikely, is that Delta dies down out in the Gulf. Until then, we watch and wait. And hope that funders and government will begin to step up. We have done our part and we’re tired. It’s time for others to help.

More like this

Hurricane Michael: How Should We Respond?