In 2024, forecasters accurately predicted an above-average Atlantic hurricane season.

From June 19, when Alberto formed, to Nov. 18, when Sara dissipated, there were 18 named storms, including seven tropical storms and 11 hurricanes (five of which were major hurricanes: Beryl, Helene, Kirk, Milton and Rafael). As we witnessed after many of this year’s storms, it only takes one event to cause massive damage.

Philanthropy can be flexible in its grantmaking and respond to acute and changing needs on the ground. CDP urges donors to plan their giving strategically, focusing on the most marginalized and at-risk people and areas.

The effects of this year’s storms will be felt for years to come, and philanthropy can make transformative investments in the equitable long-term recovery of hurricane-affected areas.

Storms are listed in reverse alphabetical order in this profile and named at the highest level they achieved.

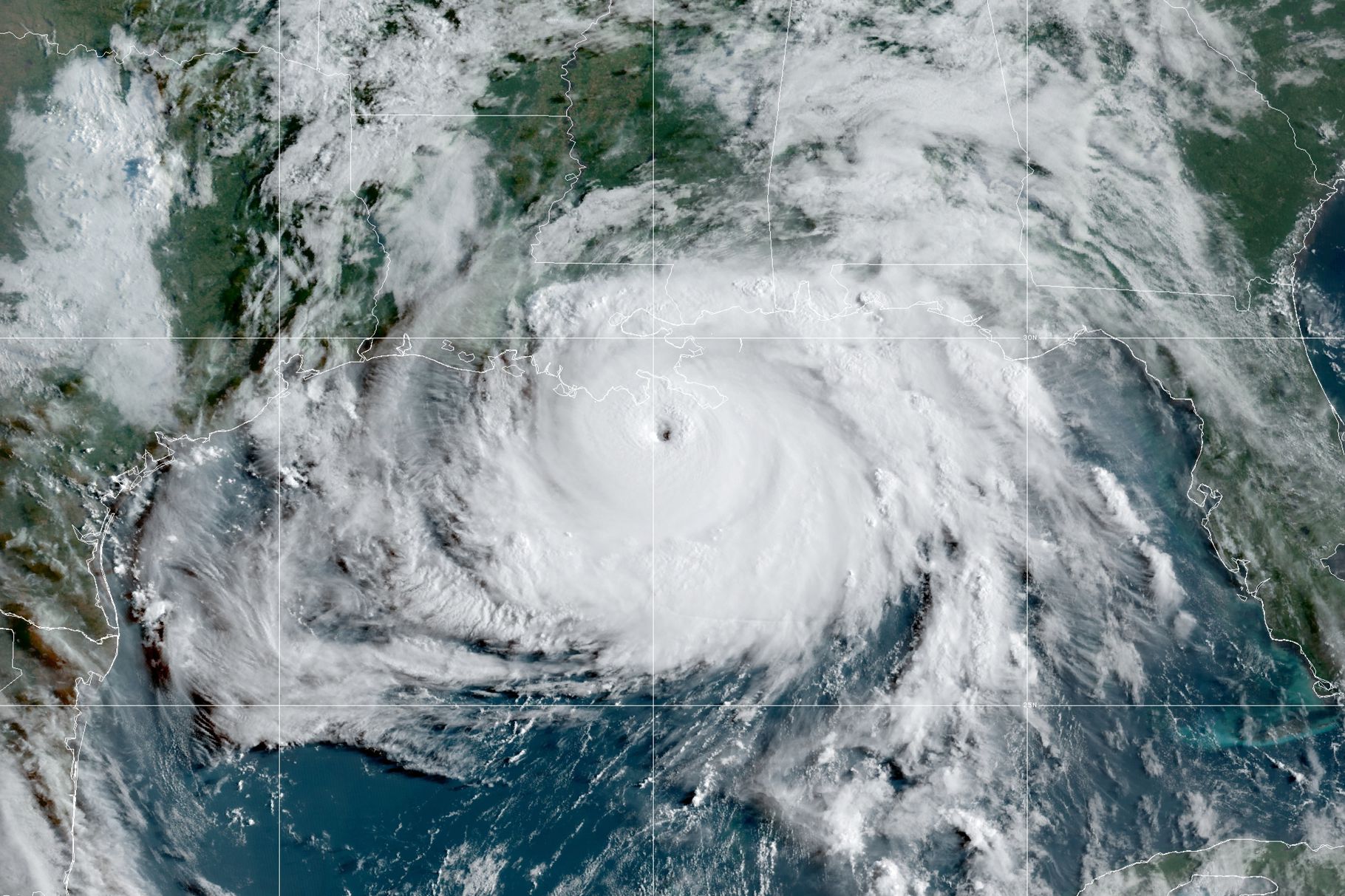

(Photo: Hurricane Ida over the Gulf of Mexico approaching Louisiana. (Source: GOES-East NOAA)

Key facts

- Originally expected to begin mid-2024, La Niña didn’t start until late December 2024. It will be a weak La Niña for the first few months of 2025 and will then transition to ENSO-neutral between March-May 2025. This was a much later start to La Niña than originally anticipated, which contributed to the location of the tropical systems in 2024.

- About 90% of global warming occurs in the earth’s oceans, and warmer ocean water played a role in the timing, intensity and location of storms in the 2024 season. Several storms experienced rapid intensification—growing in strength in a short time—which is directly attributable to warm water.

- In the last decade, flooding caused by rainfall has become the deadliest threat from tropical systems. This was very evident in Helene when flooding caused the majority of damage and deaths in Appalachia.

- There is a significant range in the average amount of assistance issued by FEMA under the Individual and Household Program (IHP), which reflects conditions of pre-disaster housing stock, poverty levels and home location. It has an impact on individuals’ and communities’ ability to rebuild. For Hurricane Milton (DR-4834), as of Dec. 17, 245,359 applicants had been approved for a total commitment of $524.6 million or an average payout of $2,138 per person. Helene, Florida’s 157,170 approved applicants received an average of $3,811 for IHP; North Carolina’s average is just $1,981, and South Carolina’s is even lower, with an average of $1,054 issued per household.

Latest Updates

Announcing nearly $3.3 million in grants from CDP’s Truist Foundation Western North Carolina Recovery and Resiliency Fund

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, November 18

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, November 11

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, November 4

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, October 14

Tropical Storm Sara – Multiple countries

Tropical Storm Sara, the 18th named storm of the 2024 hurricane season, devastated parts of Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America.

Sara made landfall near the Honduras-Nicaragua border on Nov. 14 and then moved into Belize and then Mexico on Nov. 17. At least 430,000 people were affected across Central America, with approximately 12 deaths and more than 10,000 people evacuating to shelters. The heavy rainfall amounts were similar to Eta and Iota in 2020 and included several countries in Central America.

In the early days of the tropical system, Sara killed at least two people in the Dominican Republic, led to the evacuation of nearly 1,800 people, destroyed two homes and damaged almost 500 more. In Haiti, more than 3,500 homes were damaged, and at least one person was killed.

In Honduras, the storm stalled over the country, and authorities reported that up to 40 inches of rain fell. bringing nearly 20 inches of rain, which led to nearly 128,000 people being affected, six deaths and more than 3,900 homes damaged and over 2,500 destroyed

There was also extensive infrastructure damage, including hundreds of roads and dozens of bridges damaged or destroyed.

There were two deaths and more than 1,600 families (5,000 people) affected in Nicaragua due to extreme flooding in nearly 25 rivers. More than 800 homes and six schools were damaged.

In Guatemala, over 330 homes were damaged or destroyed.

El Salvador saw 91 flooded homes and five with structural damage.

At least five people died in Costa Rica, where vehicles, roads and homes were destroyed due to landslides and floods.

In Mexico, many homes in the state of Quintana Roo lost their roofs.

Major Hurricane Rafael – Cuba & Southeast U.S.

Rafael made landfall in western Cuba on Nov. 6 as a major hurricane, the first major Gulf hurricane to hit in November in almost 40 years. Like Oscar (listed below), Rafael left 10 million people in the dark as Cuba’s electrical system collapsed due to the storm.

Rafael caused flooding in South Carolina and Georgia, 500 miles from the eye of the storm. On Nov. 6 and Nov. 7, parts of South Carolina received 12 inches of rainfall in less than 24 hours, causing extensive flooding.

Hurricane Oscar – The Bahamas & Cuba

Oscar made landfall on Great Inagua Island in the Bahamas on Oct. 20. Nearly 13 hours later, Hurricane Oscar made landfall near Baracoa in the Cuban province of Guantanamo, bringing heavy rain and intense winds to eastern Cuba and a few inches of rain to the Bahamas.

Before the storm, Cuba had been struggling with ongoing power outages for several months, and Oscar arrived with 10 million people already in the dark. At least six people were killed, and more than 1,000 homes were damaged.

According to the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, “The devastation caused by Hurricane Oscar poses a serious threat to long-term recovery, especially in key sectors like agriculture and energy. The widespread damage to critical infrastructure underscores the need for an urgent and comprehensive emergency response.”

Tropical Storm Nadine – Multiple countries

Nadine made landfall as a tropical storm on Oct. 19 near Belize City, Belize, with sustained winds of 55 mph.

The storm brought heavy rain to Belize, Guatemala and parts of Mexico before dissipating on Oct. 20. At least three people in Mexico were killed due to floods and landslides, and 1,200 homes in Chiapas were damaged by floods.

Major Hurricane Milton – Florida

Hurricane Milton grew from a tropical storm on Oct. 6 to a Category 5 storm 24 hours later, becoming the fifth-strongest Atlantic hurricane. Milton reached rare wind speeds of 180 mph, strikingly low barometric pressure and an extremely small eye, known as a ‘pinhole’. Milton made landfall in Florida near Siesta Key on Oct. 9 and was classified as a post-tropical cyclone by 5 p.m. EDT on Oct. 10 off the East Coast of Florida.

In addition to the hurricane winds, St. Petersburg experienced a 1-in-1000-year event with nearly 19 inches of rain.

While Florida sees an average of 50 tornadoes yearly, there were reports of almost 40 tornadoes before and during Milton’s landfall, and 126 warnings were issued, the highest number Florida has ever issued in one day. In Fort Pierce, six deaths were reported at the Spanish Lakes Country Club Village, a retirement community comprised of modular homes that flipped over from the winds. Milton was not expected to significantly affect this area, so the state did not issue evacuation orders. An EF-3 tornado hit Palm Beach Gardens on Florida’s eastern shore.

As of Oct. 16, there were 25 confirmed direct and indirect deaths, some from the tornadoes, across 12 counties.

“AccuWeather preliminarily estimates the total damage and economic loss from historic Hurricane Milton will be between $160 billion and $180 billion.”

Major Hurricane Helene – Southeast U.S.

Hurricane Helene made landfall on Sept. 26 near Perry, Florida, as a Category 4 storm and tied as the 14th most powerful hurricane to hit the U.S. since records began. The storm carved a 500-mile path of destruction, bringing severe winds, heavy rain, surges of 15-20 feet and mass flooding.

Helene has been called North Carolina’s “own Hurricane Katrina.” About 40 trillion gallons of rain fell, half of that in North Carolina, which saw 29 inches of rain. Many areas affected by flooding are not considered flood zones, and homeowners there were less likely to have purchased insurance from the National Flood Insurance Program.

Helene caused 220 deaths, the third-highest number of fatalities from a hurricane in the U.S. since 2000.

Accuweather has estimated Helene’s damage and economic loss to be $225-250 billion in total.

Hurricane Francine – Mexico and Southern U.S.

Tropical Storm Francine formed off the coast of Mexico and made landfall as a Category 2 hurricane in Terrebonne Parish, Louisiana, on Sept. 11. The storm brought heavy winds and torrential rains and caused severe flooding in several areas.

Significant damage was reported in the coastal areas and further inland, like New Orleans. Many communities hit by Hurricane Francine were still recovering from Hurricane Ida in 2021. Businesses and homes that were being repaired or rebuilt experienced additional damages, highlighting the need for community-wide mitigation measures.

Hurricane Ernesto – British Virgin Islands, Puerto Rico, Bermuda

Hurricane Ernesto first hit the British Virgin Islands as a tropical storm with extreme rain and strong winds on Aug. 10. The storm then moved to Puerto Rico, where it knocked out half of the island’s power on Aug. 11.

At the storm’s peak, 730,000 customers in Puerto Rico were without power, and 200,000 homes and businesses were without water. Flooding and landslides were reported in several locations. Ernesto caused about $150 million in damages.

Hurricane Debby – United States

Debby became a Category 1 hurricane overnight on Aug. 14 and made landfall in the Big Bend region of Florida at 7 a.m. EST on Aug. 5, with winds of 80 mph. About 350,000 people lost power in Florida due to the storm.

Debby drenched Florida, Georgia, North Carolina and South Carolina. Greenpond, South Carolina, reported 14 inches of rainfall, surpassing monthly averages for August in just one day.

The system moved slowly up the U.S., bringing tornadoes and flooding to Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, New York, New Hampshire and Vermont before moving into Canada.

Tropical Storm Chris

Tropical Storm Chris was a short-lived system in the southwestern Gulf of Mexico that formed as a tropical depression on June 30 in Veracruz, Mexico. It became a tropical storm that evening and dissipated the next morning. The storm caused five deaths, damaged 2,000 homes and affected over 20,000 people.

Major Hurricane Beryl – Multiple countries

As the earliest Category 5 storm on record in the Atlantic, Beryl became a tropical storm on June 28 before rapidly intensifying into a Category 5 on July 1. The storm affected multiple countries, including Venezuela, Grenada, St. Vincent and the Grenadines, Jamaica, Mexico, the U.S., and Canada. This AP photo essay depicts some of the damage.

As Beryl passed through the Caribbean islands of Grenada it caused extensive damage. Most of the businesses and homes on the islands of Carriacou (population 6,000) and Petite Martinique (population 900) were destroyed. In addition, the islands have lost hospitals, marinas (and boats), airports and almost all vegetation, including protective mangrove swamps.

Beryl passed Jamaica’s southern coast on July 4 as a Category 3 storm, leaving significant transportation, electrical and telecommunications infrastructure damage.

Weather.com reported that: “Hurricane Beryl produced more tornadoes in the U.S. than any other tropical system has in almost 19 years, from Texas to upstate New York.”

At least 44 people died in the U.S., South America and across the Caribbean, including one in Louisiana, two in Jamaica, two in St Vincent, three in both Venezuela and Grenada, and 36 in Texas.

Tropical Storm Alberto

The first named storm of the season, Tropical Storm Alberto, made landfall on June 20. It brought heavy rainfall (up to 10.5 inches in Lamar, near Rockport) and flooding to the Gulf Coast regions of Mexico and Texas. Governor Greg Abbott declared a disaster for 51 Texas counties.

Mexico experienced flooding and mudslides in the Northeast. In Nuevo Leon, Mexico, four deaths were reported, three of whom were youths aged 12 to 16

2024 “Fish Storms”

A “fish storm” is a tropical system that does not make landfall and causes no damage. They can range in intensity from tropical depressions to major hurricanes. Six storms this year qualified as fish storms, including Hurricane Patty, Hurricane Leslie, Hurricane Kirk (major), Tropical Storm Joyce, Hurricane Isaac and Tropical Storm Gordon.

While there are many immediate needs following hurricanes, funders should consider designating funds for the affected communities’ anticipated intermediate and long-term needs.

Cash assistance

Unrestricted monetary donations to support affected individuals and families are critical. Direct cash assistance can allow families to secure housing, purchase necessities, and contract local services that address their needs. It gives each family flexibility and choice, ensuring that support is relevant, cost-effective and timely.

Cash assistance can also help move families toward rebuilding their lives faster. It can also provide a much-needed jolt to local economies, which can be a major boon to recovery.

Housing

People whose homes were damaged will need support repairing damage and/or securing new or temporary housing that is safe and affordable. After a hurricane, displaced residents may face challenges finding housing.

In many parts of the country, demand for housing outpaces supply, complicating recovery efforts. Affected people living in rural areas or public housing and people from marginalized groups may require assistance identifying and securing housing. The ability to rebuild in rural communities is also challenging due to reduced economies of scale and the cost of transporting goods.

Affordability

The United States is facing a critical housing shortage of more than 7 million affordable homes for the nation’s more than 10.8 million extremely low-income families.

Many people in the U.S. regularly struggle to find safe and affordable housing. Add a major disaster into the equation, and it becomes even more challenging to find affordable housing, especially for low and middle-income residents and/or retirees on fixed incomes.

Manufactured housing

The housing affordability crisis is worse for people who live in manufactured (also called mobile) homes. While physically vulnerable to hurricanes, manufactured housing represents a very affordable and accessible housing option, but insurance is limited.

CDP hosted a webinar about the increased risks manufactured homes face and their role in disaster recovery. Additionally, the Manufactured Home Disaster Recovery Playbook, created by Matthew 25 in 2023 for CDP, has videos, lessons learned and other information to assist funders in supporting manufactured home disaster recovery.

Insurance

After a hurricane, even those with insurance may not be covered depending on the type of insurance a person has and the damage their homes incurred. Hurricanes often cause flash flooding, but people experiencing flood damage must have a separate policy through the National Flood Insurance Program to be covered.

Numerous companies have withdrawn from the home insurance market in states nationwide, including Louisiana and Florida. Finding insurance is increasingly difficult and more expensive.

CDP hosted a webinar on June 13 about the impact of disasters on insurance coverage.

Rural communities

Rural communities do not always have access to robust social service support, particularly disaster recovery support. As a result, many rural families are more vulnerable to the impact of disasters, especially those that do not garner much media attention.

According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, more than 50% of all manufactured homes are in rural areas around the U.S.

Recovery in rural communities is slower and requires “patient dollars.” Funders must understand that progress will not occur as quickly as in larger, more well-resourced communities. Investments should be made over time: Pledges of multi-year funding are very helpful, as is support for operating costs and capacity building.

Funders would, however, be wise to remember that while many rural communities do not have access to the same level of financial assistance as some urban areas, the social fabric and human capital available in these areas can be powerful assets for recovery.

Health and excess deaths

In-direct deaths will continue for years to come after a hurricane. New research estimates that the average cyclone in the U.S. brings about 7,000 to 11,000 excess deaths.

Lack of access to medication, lack of treatment for chronic health conditions, stress, mental illness, infectious diseases and lower socioeconomic status all contribute to these additional deaths, according to a study published in Nature.

The CDP Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund is a perpetual fund, allowing CDP the most flexibility to respond to philanthropic and humanitarian needs as they arise. You can donate to the fund to support recovery.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you have questions about donating to the CDP Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund, need help with your disaster-giving strategy or want to share how you’re responding to this disaster, please contact development.

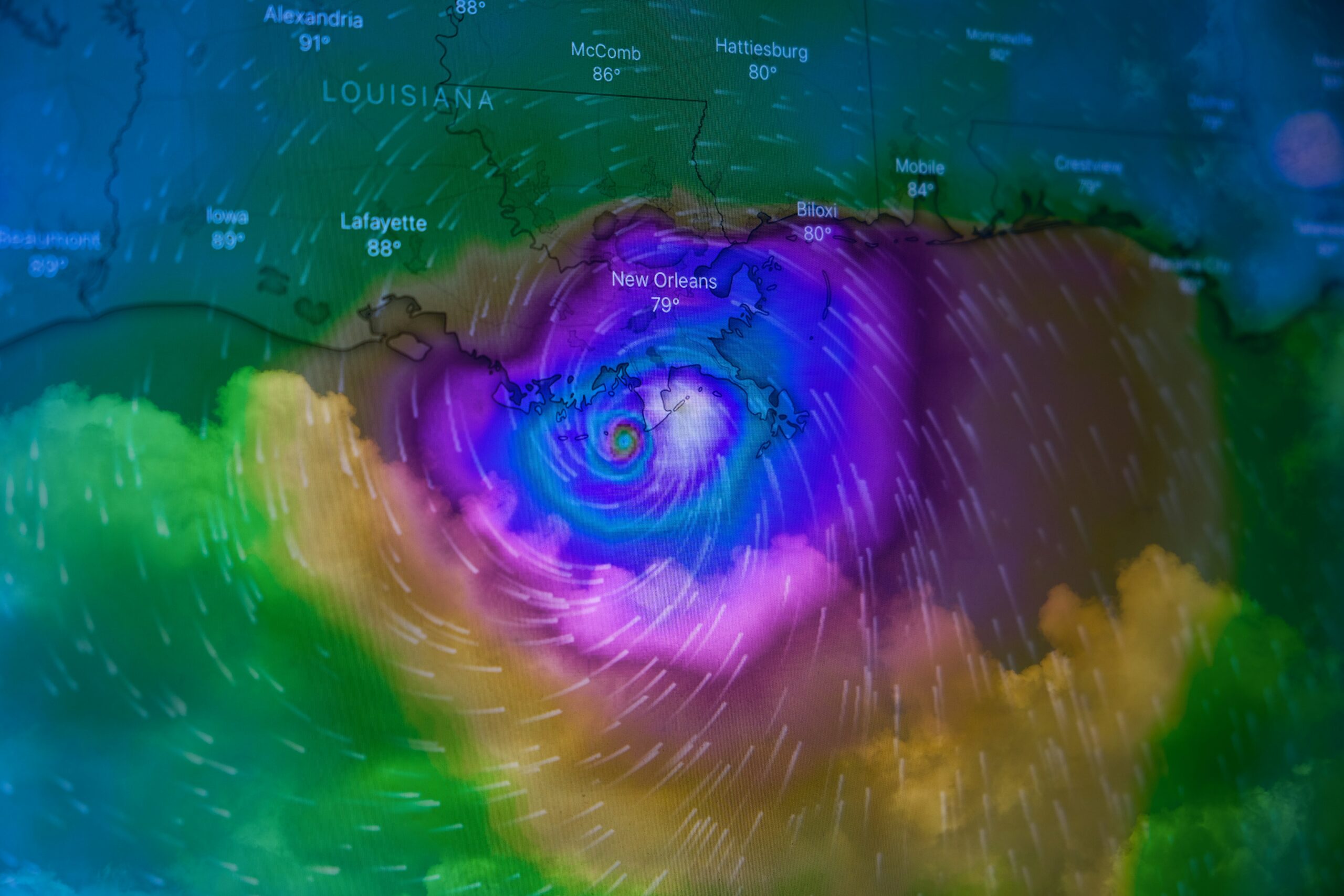

(Photo: Hurricane Ida approaching New Orleans on August 29, 2021. Photo by Brian McGowan on Unsplash)

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working on recovery from this disaster to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Resources

Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

Tropical cyclones (also known as hurricanes and typhoons) pose significant global threats to life and property, bringing a variety of hazards, including storm surges, flooding, extreme winds and tornadoes. Funders can intervene to reduce harm to people and property, before, during and after storms.

Tornadoes

Tornadoes are powerful storms that can cause considerable damage to communities. They can break branches from trees or lift houses off their foundations. The speed with which they form, and their variable intensity, make them some of the most unpredictable disasters on the planet.

Floods

Flooding is our nation’s most common natural disaster. Regardless of whether a lake, river or ocean is actually in view, everyone is at some risk of flooding. Flash floods, tropical storms, increased urbanization and the failing of infrastructure such as dams and levees all play a part — and cause millions (sometimes billions) of dollars in damage across the U.S. each year.