Last updated:

Hurricane Florence

Overview

Hurricane Florence began as a disturbance near the Southern Cabo Verde Islands on Friday, Aug. 30, 2018, and was named Tropical Storm Florence on Sept. 1.

Hurricane Florence began as a disturbance near the Southern Cabo Verde Islands on Friday, Aug. 30, 2018, and was named Tropical Storm Florence on Sept. 1. Initially projected to pose no threat to land, it became the third named hurricane of the 2018 Atlantic season on Sept. 4, fluctuating in intensity and dropping to a tropical storm again before increasing to a Category 4 hurricane on Sept. 10, threatening the Eastern seaboard. Florence made landfall near Wrightsville Beach (near Wilmington) in North Carolina at 7:15 a.m. Sept. 14 as a Category 1 hurricane, bringing a massive storm surge and sustained winds of up to 85 mph.

(Photo: U.S. Army Soldiers assigned to the 1-118th Infantry Battalion, South Carolina Army National Guard conduct traffic control points alongside S.C. Highway Patrolmen in Mullins, S.C. Sept. 20, 2018. Source: U.S. Army National Guard Photo by Staff Sgt. Jorge Intriago)

The system inundated North Carolina and South Carolina with torrential rain for days. After the rivers crested, the water moved downstream, continuing flood conditions and road closures. Florence was the eighth-wettest tropical cyclone to hit the mainland United States – and the wettest ever to hit North Carolina. The slow impact of a flooding disaster resulted in South Carolina feeling the biggest impacts towards the end of September, almost two weeks after landfall.

According to Weather.gov, “After the eye crossed Wrightsville Beach, NC at 7:15 a.m. the storm spent the next two days producing record-breaking rainfall across eastern North Carolina and a portion of northeastern South Carolina. Over 30 inches of rain were measured in a few North Carolina locations, exceeding the highest single-storm rainfall amounts ever seen in this portion of the state. A station in Loris, SC recorded 23.63 inches of rain, setting a new state tropical cyclone rainfall record for the state of South Carolina. Record river flooding developed over the next several days along the Cape Fear, Northeast Cape Fear, Lumberton, and Waccamaw Rivers, destroying roads and damaging thousands of homes and businesses. A USGS report indicated nine river gauges reported floods exceeding their 1-in-500 year expected return intervals. Although Florence will be remembered primarily for its record-breaking flooding, wind gusts over 100 mph caused significant damage to buildings, trees, and electrical service across the Cape Fear area, and a storm surge of over four feet eroded beaches and damaged property between Cape Fear and Cape Lookout.”

Due to the effects of the storm, Florence was retired from the list of possible hurricane names and will be replaced by Francine in 2024.

Latest Updates

Announcing 10 New Recovery Grants for North Carolina and Florida

When Donors Prioritize Disaster Funding

Announcing the 2018 Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund

What was the impact on the communities?

(Source: Customs and Border Protection photo by Jaime Rodriguez Sr.)

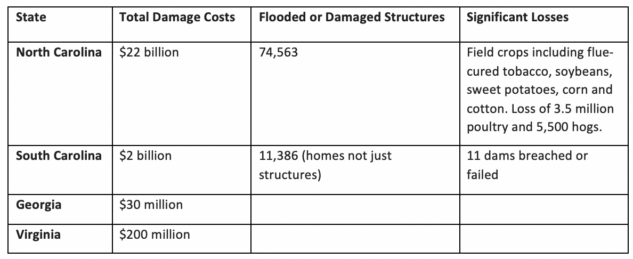

Despite being a Category 1 storm, Florence was a very expensive event due to the extensive flooding. According to the National Centers for Environmental Information, the financial impact was $24.7 billion. They said: “The total damage from Florence in North Carolina is more than the cost experienced during Hurricane Matthew (2016) and Hurricane Floyd (1999) combined.”

A May 2019 report from the National Hurricane Center found:

There were 54 fatalities associated with the storm. There were 40 deaths in North Carolina (25 indirect deaths and 15 direct fatalities, including 11 due to motor vehicle accidents in freshwater flooding and four due to wind causing trees to fall). In South Carolina, there were nine deaths (5 indirect and 4 direct all due vehicle accidents in freshwater flooding). There were also three direct fatalities in Virginia (two from freshwater flooding and one from a tornado), as well as two deaths in Florida due to drowning.

Housing

As noted above, thousands of homes and structures were flooded. While basic gutting has occurred in most areas, there are still many homes that have yet to be rebuilt. Some homeowners will be engaged in a strategic buyout and will need to secure new housing elsewhere, while others may choose to a community they perceive as safer. Many grants to support housing projects and repairs were only released in September 2020 and people have been dealing with housing issues for two years.

Agriculture

The huge impact on the agricultural community is of particular concern to small, individual or family farmers. African-American farmers continue to suffer additional land loss as a result of this storm, especially given its proximity to Hurricane Matthew. See this impact story in the Disaster Philanthropy Playbook to see how CDP’s grant to the Land Loss Prevention Project helped address this issue.

Economic/Community Development

Business recovery is always an important component of disaster recovery. It is hard for businesses to withstand the shock of a disaster, let alone two only two years apart.

Physical and Mental Health

When storms follow one after another, as occurred with Hurricane Matthew in 2016 and Hurricane Florence in 2018, there is an increased strain on mental health which can then affect physical health. PTSD is common after disasters, especially for children. Most government case management or counseling programs are short-term and there is a need for ongoing trauma-informed support services.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you would like to make a donation to the 2018 Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund, please contact development.

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working on recovery from this disaster to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

Donor recommendations

If you are a donor looking for recommendations on how to help with disaster recovery, please email Regine A. Webster.

Philanthropic and government support

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy created a 2018 Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund. This fund made five grants for Hurricane Florence as follows:

- CORE Community Organized Relief Effort was awarded $250,000 to support their North Carolina Housing Rehabilitation and Resiliency Program in Robeson County which targeted the Lumbee Native American community to assist with housing repairs and with building community resilience through local capacity-building efforts. Read our Playbook Impact Story about this work.

- Disabilities Rights North Carolina received $150,000 to improve disaster services and assistance through indirect and direct assistance to people with disabilities, advocacy and more inclusive emergency management planning.

- Land Loss Prevention Projectreceived $50,000 for staff support to provide legal services to address immediate critical needs of homeowners, landowners and farmers in the 34 disaster recovery counties.

- North Carolina Baptists on Mission was awarded $263,717 to provide direct support and assistance for housing repairs to 60 families using their three program support hubs (Robeson, Craven and Duplin counties) which fed, housed and mobilized up to 300 volunteers a day.

- Rebuilding Together of the Triangle received $200,000 for the critical repair of 20 homes in Bladen and Pender counties.

The Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy map compiled by Candid identified $54.5 million in 178 philanthropic grants for Hurricane Florence including:

- Hanes (through their Hanesbrands Inc. Contributions Program) partnered with Delivering Good to distribute essential basic apparel valued at more than $2 million to storm and flood victims including nearly 350,000 pairs of underwear, socks and t-shirts.

- The State Employees’ Credit Union Foundation made a $1 million grant to the North Carolina Association of Feeding America Food Banks to assist individuals in the counties directly impacted by the storm. This grant supported the food banks and helped to provide water, food, cleaning supplies, and other essentials.

- Rebuilding Together received a grant of $350,000 from Charter Communications Inc. Contributions Programto support relief efforts and specifically assist with home repairs and renovations needed in areas impacted by Hurricane Florence.

- The Greater New Orleans Foundation provided both SBP and the North Carolina Community Foundation with $5000 grants to assist in immediate response efforts on the ground in North Carolina after Hurricane Florence.

FEMA declarations were issued for North Carolina (DR-4393), South Carolina (DR-4394) and Virginia (DR-4401). In North Carolina, all of the counties in the southeast region of the state received Individual Assistance and Public Assistance (Categories A-G) declarations, while another 22 counties across the state received a mix of these programs. In total, 34,713 applications were approved for Individual Assistance for a total of $134 million. Almost $639 million has been obligated in the Public Assistance program and just over $22 million has been obligated for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

As of Sept. 2020, FEMA reported that nearly $2 billion in state and federal assistance had been provided to communities and individuals. This includes:

- “$407.8 million in loans approved by SBA for homeowners, renters and businesses affected by the hurricane.

- $632.7 million paid by the NFIP to flood insurance policyholders across the state.

- FEMA provided housing, without cost, to 656 households approved to live temporarily in travel trailers or manufactured housing units in the 13 hardest-hit counties—Bladen, Brunswick, Carteret, Columbus, Craven, Duplin, Jones, Lenoir, New Hanover, Onslow, Pamlico, Pender and Robeson. By June 2020, all 656 households had moved into longer-term housing.

- FEMA provided $628.9 million to reimburse state and local governments and certain private nonprofits in 51 affected counties for eligible activities and disaster-related costs. An additional $197.1 million has been provided by the state.”

Eight counties in the northeast area of South Carolina received Individual Assistance and Public Assistance (Categories A-G) declarations, while 12 other counties across the state received a mix of these programs. In total, 5,175 applications were approved for Individual Assistance for a total of just over $24.5 million. Almost $99 million has been obligated in the Public Assistance program and just over $2 million has been obligated for the Hazard Mitigation Grant Program.

In Virginia, 16 counties were approved for public assistance, but no total of dollars obligated has been provided.

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Fund resources

Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

Hurricanes, also called typhoons or cyclones, bring a triple threat: high winds, floods and possible tornadoes. But there’s another “triple” in play: they’re getting stronger, affecting larger stretches of coastline and more Americans are moving into hurricane-prone areas.

Is your community prepared for a disaster?

Explore the Disaster Playbook