What We Can Learn from Five Years of Mapping Disaster-Related Giving

For the past five years, the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) and Foundation Center have tracked grantmaking for disasters and humanitarian crises. The goal: to provide comprehensive data on disaster giving, so that philanthropists, government agencies and NGOs have the information they need to be better able to coordinate, make more strategic decisions based on data […]

For the past five years, the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) and Foundation Center have tracked grantmaking for disasters and humanitarian crises. The goal: to provide comprehensive data on disaster giving, so that philanthropists, government agencies and NGOs have the information they need to be better able to coordinate, make more strategic decisions based on data and thereby be more effective in their disaster philanthropy and assistance.

In November 2018, we launched the fifth edition of the Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report. In addition to the annual overview of disaster giving, this edition also included a five-year trends analysis based on disaster funding by 1,000 of the largest U.S. foundations between 2012 and 2016.

So what can we learn from this look back?

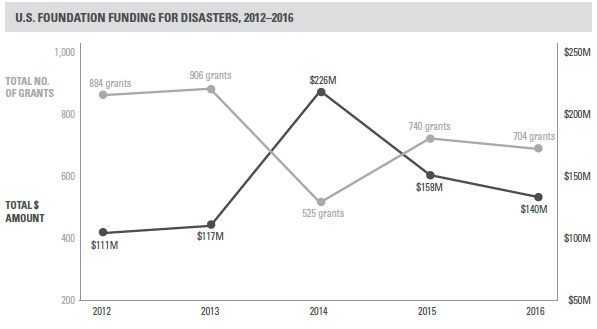

As might be predicted, disaster funding tends to be episodic and dependent upon the crisis. On average, large U.S. foundations contributed $150.4 million per year to disasters. There was a dramatic spike in 2014 due to large grants in response to the Ebola outbreak, after which funding declined over the next two years.

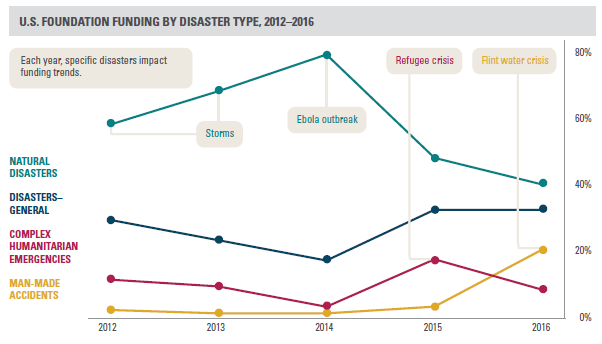

Natural disasters were the largest focus for funders during the five years in question. In 2015, foundations increased their funding for complex humanitarian emergencies in response to the Syrian war and the refugee crisis. Man-made accidents accounted for no more than 3 percent of dollars every year, except in 2016 when funding jumped to 20 percent due to efforts to respond to the contamination of drinking water in Flint, MI. We categorize grants with no specific disaster focus or grants that support multiple unrelated disasters as “Disasters-General”.

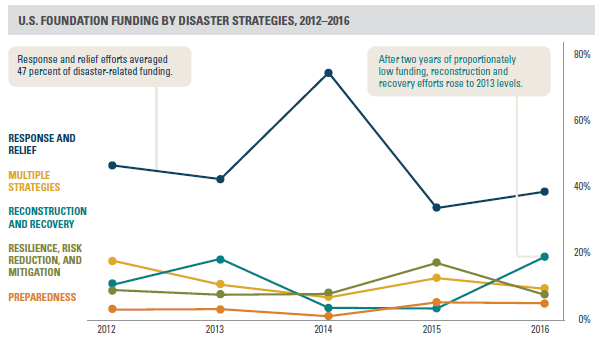

In addition to looking at what crises and disasters funders respond to, we are also interested in analyzing at what stage funders step in. Attention is often focused on communities in the immediate aftermath of a catastrophe. However, there are other points on the disaster lifecycle, such as disaster risk reduction and preparedness, when funders can step in to help minimize the economic, social and human consequences of disasters.

In the five-year analysis, urgent and immediate support, which we code as response and relief efforts, were the most funded assistance strategy. Across all years, funding for response and relief averaged 47 percent of all disaster funding, peaking in 2014 to 73 percent due to large grants addressing the Ebola outbreak. Recovery efforts, or more longer-term efforts, increased in 2013 after Superstorm Sandy and in 2016 following the Flint water crisis. Resilience and risk reduction funding increased slightly in 2015 in the wake of the Ebola outbreak.

The five-year trends analysis is based on all grants of $10,000 or more reported by 1,000 of the largest U.S. foundations, which accounts for approximately half of the total grant dollars awarded by the universe of independent, corporate, community and grantmaking operating foundations in the U.S.

The five-year trends analysis is based on all grants of $10,000 or more reported by 1,000 of the largest U.S. foundations, which accounts for approximately half of the total grant dollars awarded by the universe of independent, corporate, community and grantmaking operating foundations in the U.S.

For a broader picture of disaster philanthropy, including bi- and multi-lateral donors, the U.S. federal government, corporations, individuals and funding beyond the largest U.S. foundations, you can visit disasterphilanthropy.foundationcenter.org. Here you will find an interactive dashboard which lets you look at aggregated funding data by year, as well as a disaster funding map, which has grant- and project-level data from 2011 onward. There are tutorials to help you go deeper into the report and related tools here.

So what does all this mean? And what can funders do?

Share your data

We acknowledge that there are more disaster contributions than we currently document. We invite and encourage donors to share data with us to help further improve these tools. We collect grants data from hundreds of funders, mostly through their 990 tax forms which can take up to two years to be available and often do not contain the amount of information needed for us to best code and analyze the data.

However, funders can also choose to send their grants data directly to us, which helps make our tools timelier. As we work to improve and streamline our data collection and analysis, funders, we need your help. We would love for more funders to submit their grants data to us directly—and do it often! Grants that are reported directly to us can include more nuance and details, allowing us to better categorize and code them, thereby gaining better insight. If you want to start sharing your data with us, have any questions or want more information, visit: foundationcenter.org/gain-knowledge/foundation-data/share-your-grants-data

Go beyond funding for immediate relief

There is no doubt that we need funders to be nimble and able to respond to disasters as soon as they occur with immediate response and relief efforts. However, we also need funders to be strategic and think about the larger disaster life cycle. This means helping communities prepare for disasters, through resilience and mitigation efforts, as well as taking a longer-term view by supporting reconstruction and long-term recovery efforts. Some examples of funders working beyond immediate relief efforts include: The Kresge Foundation, which gave a grant to the Gulf Restoration Network in 2016 to increase the flood resilience of communities in New Orleans and Southeast Louisiana through the implementation of comprehensive stormwater management practices and other nonstructural flood-mitigation measures. And the W.K. Kellogg Foundation, which gave a grant to the Haiti Christian Development Fund in 2017 to assist local smallholder farmers in Haiti recover from the impact of Hurricane Matthew through technical assistance, training and marketing assistance.

It is encouraging that 2016 saw an increase in funders giving to reconstruction and recovery efforts however, giving to preparedness and mitigation activities have remained low.

Plan for disasters

Even if your organization does not have a specific program for disasters or humanitarian relief, all funders might find themselves stepping in as disaster funders at certain points in time. There are things funders can do before a disaster strikes to plan for more effective, intentional giving. CDP’s Disaster Philanthropy Playbook is a great resource. Jointly created with the Council of New Jersey Grantmakers, the Playbook offers concrete tips and best practices to guide grantmakers in responding to future disasters. Additionally, the Funding Map allows donors to filter by geographic region, disaster type and disaster strategy to look at granular level grants data and see how others have responded to previous disasters.

We hope these tools can assist donors in considering how to best maximize the impact of their disaster-related giving and we welcome your help in making them better.

More like this

New Data Sources and Five-Year Trends Highlight New Disaster Philanthropy Report