Following the lead of the World Health Organization (WHO), CDP “remove[d] the distinction between endemic and non-endemic countries, and report[ed] on countries together where possible, to reflect the unified response that is needed,” except in reference to historical information.

On Nov. 28, 2022, WHO announced that it would begin to use mpox, alongside monkeypox for one year, after which the official name of the virus would become mpox.

Beginning in May 2022, cases of mpox (formerly monkeypox) were reported in areas around the world where it was not traditionally seen. When CDP first began tracking it on May 23, 2022, there were less than 100 cases confirmed in several non-endemic countries. The U.S. had only one confirmed case and two suspected cases.

According to TIME Magazine: “Monkeypox was first identified in the 1950s. Prior to the current outbreak, it was endemic to parts of western and central Africa, with cases often linked to exposure to infected animals. The current outbreak is unusual in its scale, global reach, and spread from person to person. Experts are still trying to figure out why that is, but possible explanations include viral mutations, declining use of the smallpox vaccine, and shifts in human behavior.” The first human case appeared in the 1970s.

The 2022 outbreak was traced to several mid-spring gatherings (mostly circuit parties and raves) for men within the LGBTQIA+ community in Europe. These were followed by Pride celebrations across the world, and the June/July surges were attributed to those events. Similarly, the relatively quick subsidence of cases was also traced to actions from the LGBTQIA+ community.

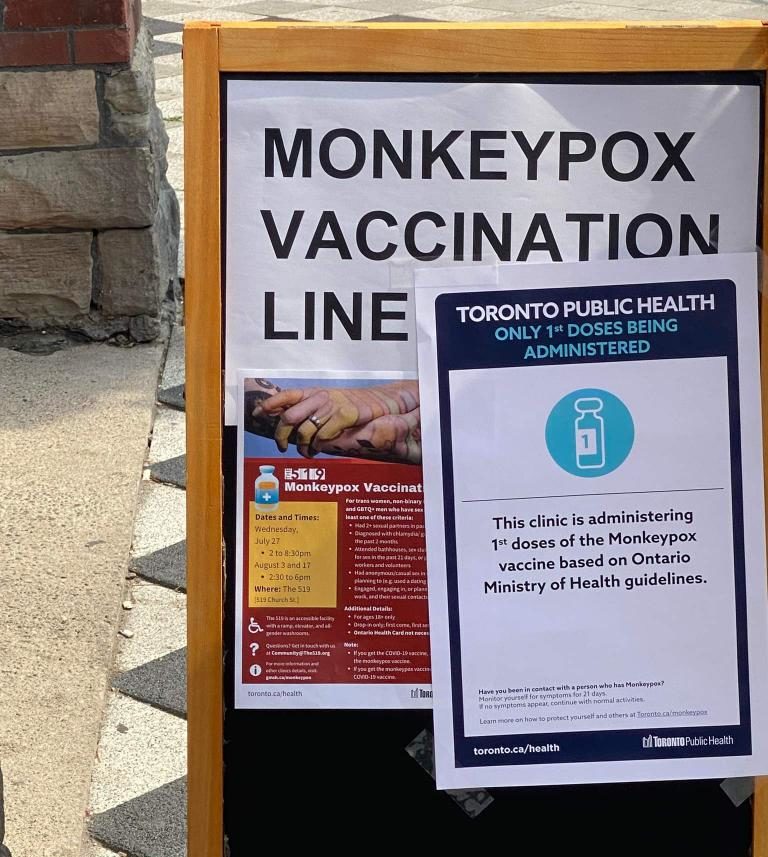

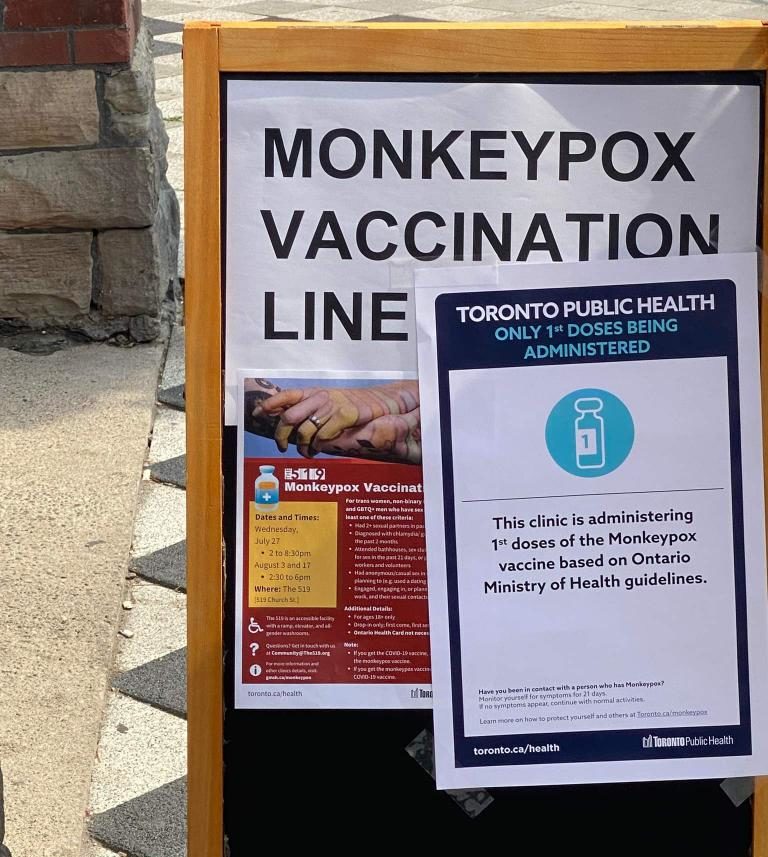

(Photo: Monkeypox vaccination site in Toronto, Canada. Photo credit: TJ Cutland)

Mpox is part of the orthopoxvirus genus. While similar to smallpox, it is usually less severe but can cause rashes, fever, headaches, muscle and backaches and swollen lymph nodes. Unlike the Congo Basin strain, which has a 10% fatality rate, the West Africa strain that spread in 2022 had a 1% fatality rate. There were 65 deaths in 2022 (as of Dec. 16).

However, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), “people with weakened immune systems, children under 8 years of age, people with a history of eczema, and people who are pregnant or breastfeeding may be more likely to get seriously ill or die. Although the West African type is rarely fatal, symptoms can be extremely painful, and people might have permanent scarring resulting from the rash.”

Latest Updates

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, October 11

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, October 3

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, September 26

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, September 19

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, August 29

Key facts

- According to WHO, “This [was] the first time that cases and sustained chains of transmission [were] reported in countries without direct or immediate epidemiological links to areas of West or Central Africa.”

- With the exception of those regions, the majority of cases (86.2%) occurred among men who have sex with men, including gay and bisexual men.

- Overall, the severity of mpox is quite low. While extremely painful, most cases were managed without hospitalization and only 65 deaths were reported up to Dec. 16.

- Anyone can catch mpox, although the majority of cases in the 2022 outbreak were linked to sexual transmission.

- It is uncertain whether mpox can be eradicated in non-endemic countries, although some researchers think it is likely to become endemic in more places.

By the numbers

As of Dec. 16, 2022, 82,762 global cases had occurred in 110 countries across all six of WHO’s regions. The highest number of cases were found in the U.S. (29,687 cases and 20 deaths), followed by Brazil (10,252 cases and 14 deaths), Spain (7,416 cases and three deaths), France (4,110 cases and no deaths), Colombia (3,908 cases and no deaths) and the United Kingdom (3,730 cases and no deaths). These six countries, together with Germany, Peru, Mexico and Canada, represented 85.9% of cases reported. The transmission rate had slowed dramatically after the U.S. summer months in most places; for example, Germany only increased by four cases between mid-November and mid-December 2022.

Overall, the new cases had decreased by 45.6%% between Dec. 5 and Dec. 11, compared to the previous week. According to WHO, as of Dec. 11, 2022, 12 countries reported an increase in their cases. In the week prior to that date, the highest increase reported was from Mexico. There were 73 countries that had not reported any cases in the 21 days prior to Dec. 11 in the same time period, the Region of the Americas had 93.4% of the cases and the European Region had 5.6% of the cases.

U.S. public health emergency

Given the high rate of mpox within the U.S., the Biden administration declared monkeypox/mpox a public health emergency on Aug. 4. This allowed Health and Human Services (HHS) to access funds and hire new staff.

As of Dec. 16, mpox had been found in every state across the U.S. New cases had fallen to an average of five per day (Dec. 14), down from the peak of 627 on Aug. 1. The highest overall number was in California (5,622) with New York state (4,184) ranking second.

The first U.S. death was confirmed in California on Sept. 12. The death of a man in Ohio was announced on Sept. 29. After that point, an additional 18 deaths were recorded in the U.S.

A disproportionate number of people in the U.S. who contracted mpox were Black and Hispanic men. As of Dec. 4, 55% of cases were Black or African-American and 14% were Hispanic or Latino, compared to 21% white. By comparison, 59.3% of people in the U.S. are white (non-Hispanic), 13.6% are Black and 18.9% are Latino.

Men who have sex with men (MSM)

Like HIV in the 1980s, the majority of cases in this outbreak to date were among men who have sex with men (including gay and bisexual men) and their close associates. The term MSM was used to capture this as not all individuals engaging in same-gender sexual encounters identify as gay or bisexual.

Nonetheless, this association resulted in a form of “gay panic” and an opportunity for those opposed to LGBTIA+ rights to seize on the disease as a moral failure.

WHO has analyzed and traced a number of the cases. They have reported (as of Dec. 16):

- “96.8% of cases with available data are male, the median age is 34 years.

- Males between 18-44 years old continue to be disproportionately affected by this outbreak as they account for 79.7% of cases.

- Among cases with known data on sexual orientation, 86.1% identified as MSM. Of those identified as MSM, 5.3% were identified as bisexual men. For women, the available data shows that 87% are heterosexual.

- Among those with known HIV status, 51.6% were HIV-positive. Note that information on HIV status is not available for the majority of cases, and for those for which it is available, it is likely to be skewed towards those reporting positive HIV results.

- 942 cases were reported to be health workers. However, most were infected in the community and further investigation is ongoing to determine whether the remaining infection was due to occupational exposure.

- Of all reported types of transmission, a sexual encounter was reported most commonly, with 70.5of all reported transmission events. [This was a decrease from earlier in the outbreak when the rate was over 90%.]

- Of all settings in which cases were likely exposed, the most common was in party settings with sexual contacts, 59.1% of all likely exposure categories.”

Children and discrimination

According to a WHO analysis, 571 cases were found in children under 18 (1.2%), and of these, 148 were children ages 0-4 (0.3%). As of Dec. 16, there had been over 696 cases of Mpox detected in children and youth under 20 across the U.S. This includes: 20 children aged 0 to 5, nine aged 6 to 10, 11 aged 11 to 15 and 636 cases in people aged 16 to 20.

According to the CDC, while mpox can be spread through sexual contact, it is not the only mode of transmission. Anyone can get mpox if they have close personal contact with someone who has symptoms of mpox. Household transmission such as shared towels, clothing and bed linens is seen as the primary cause for cases in children. Despite this, homophobic opponents of equal rights are pointing to infections in children and CDC Director Rachelle Walensky’s describing children as “risk-adjacent” as proof of pedophilia, even though mpox is not considered to be a sexually transmitted disease (STD) (and even if it was an STD, household transmission is possible through activities of daily living).

Critique of the name

Due to increasing criticism of the name “monkeypox” to describe the virus, especially within the U.S., actions were taken to rename the virus.

According to the New York Times, “Public health researchers say the term evokes racist stereotypes, reinforces offensive tropes about Africa and abets stigmatization that can prevent people from seeking care.”

The WHO held an open process to rename the disease the virus causes. It agreed upon mpox. Both names were to be for a year to alleviate concerns of changing the name in the midst of an outbreak.

The variants have been reclassified as Clade I (previously The Congo Basin variant) and Clade II (previously West African variant). There were two sub-clades (or sub-variants) Clade IIa and Clade IIb. It is Clade IIb that primarily circulated.

WHO declaration

Two meetings of the International Health Regulation Emergency Committee (IHR Emergency Committee) were held – one in June and one in July – to determine whether WHO should declare mpox a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). In June, the IHR Emergency Committee felt there was not enough evidence to make such a declaration and in July, the committee could not reach a consensus. As a result, Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General of the WHO, made the decision to break the deadlock and declared mpox as a PHEIC. This has also been done for several diseases, the most recent in January 2020 for COVID-19.

CNBC states, “The rare designation means the WHO now views the outbreak as a significant enough threat to global health that a coordinated international response is needed to prevent the virus from spreading further and potentially escalating into a pandemic. Although the declaration does not impose requirements on national governments, it serves as an urgent call for action. The WHO can only issue guidance and recommendations to its member states, not mandates. Member states are required to report events that pose a threat to global health.

Vaccines, testing and treatment

As with many viruses, vaccines and testing were the key to reducing transmission and preventing mutations. While there were several vaccine and testing clinics, and information hotlines across the country, they were limited to primarily urban areas. Additionally, tests, vaccine supplies and human and other resources are limited.

The extensive outreach by community health clinics and HIV/AIDS or LGBTQIA+ organizations in the U.S., Canada and other countries was instrumental in reducing the spread of the virus. University of South Florida College of Public associate professor Jill Roberts said, “The community that largely was affected was very responsible … If that had not been the case, we would have definitely seen a lot of spread well beyond the men who have sex with men population and into other populations.”

During any epidemic, funders can work with their local public health entities to increase capacity to test, treat and vaccinate while also supporting vaccine and test production. The primary focus should be on community clinics in partnership with local organizations. Use the Find a Community Health Center tool in the U.S. to find a clinic near you.

Supporting LGBTQIA+ and HIV/AIDS organizations

As mentioned, this virus primarily affected men who had sex with men. They were the population most at-risk and therefore were the initial population for vaccines. However, most LGBTQIA+ organizations or HIV/AIDS are underfunded. According to Funders Concerned About AIDS, HIV patient advocacy funding has been flat for almost a decade and may be declining. CEO of Community Access National Network, Jen Laws, said, “This is the equivalent of underinvesting in public health infrastructure from the patient advocacy perspective – we cannot prioritize the experiences of patients, their wellbeing, and ultimately inform public policy without these supports.”

Best practices to reach a marginalized population include using members of that community and familiar organizations to convey critical messaging. Support capacity-building and opportunities for education and outreach. Given the homophobia that became evident, there continues to be a need to also support the overall capacity of these organizations to help their communities with emotional health.

Given the high levels of misinformation about mpox, GLAAD asked all social media platforms to follow Twitter’s lead in redirecting viewers to HHS’s monkeypox website.

Contact tracing

Over the years, one of the best techniques to reduce Ebola outbreaks has been the use of contact tracing. An effective and vigorous contact tracing program is useful for any epidemic, especially one like monkeypox which has a long incubation period.

When people are informed of their exposure early, they can isolate, monitor their symptoms, get tested and access vaccines without waiting for the disease to progress. Contact tracing programs, often used in public health for infectious diseases, need to be stood up or expanded whenever an outbreak occurs. Because of the affected population in mpox, much of the contract tracing was done by or in conjunction with organizations that work with the LGBTQIA+ population. In other epidemics, using culturally-competent service providers is critical.

Emotional support

Overall, there is going to be an ongoing need for counseling and other emotional support initiatives. For many MSM, this virus was a reminder of the losses throughout the HIV/AIDS pandemic. For others, their ongoing battles with HIV or AIDS was aggravated by mpox and may have created additional trauma.

Because of the global nature of the virus, two CDP funds are available to respond to the outbreak: CDP Global Recovery Fund will provide support internationally and CDP Disaster Recovery Fund will provide support in the United States and its territories. CDP is also tracking organizations that are responding. We are in contact with and can grant to organizations that are not 501(c)3 entities.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you would like to make a donation to the CDP Global Recovery Fund or the CDP Disaster Recovery Fund, please contact development.

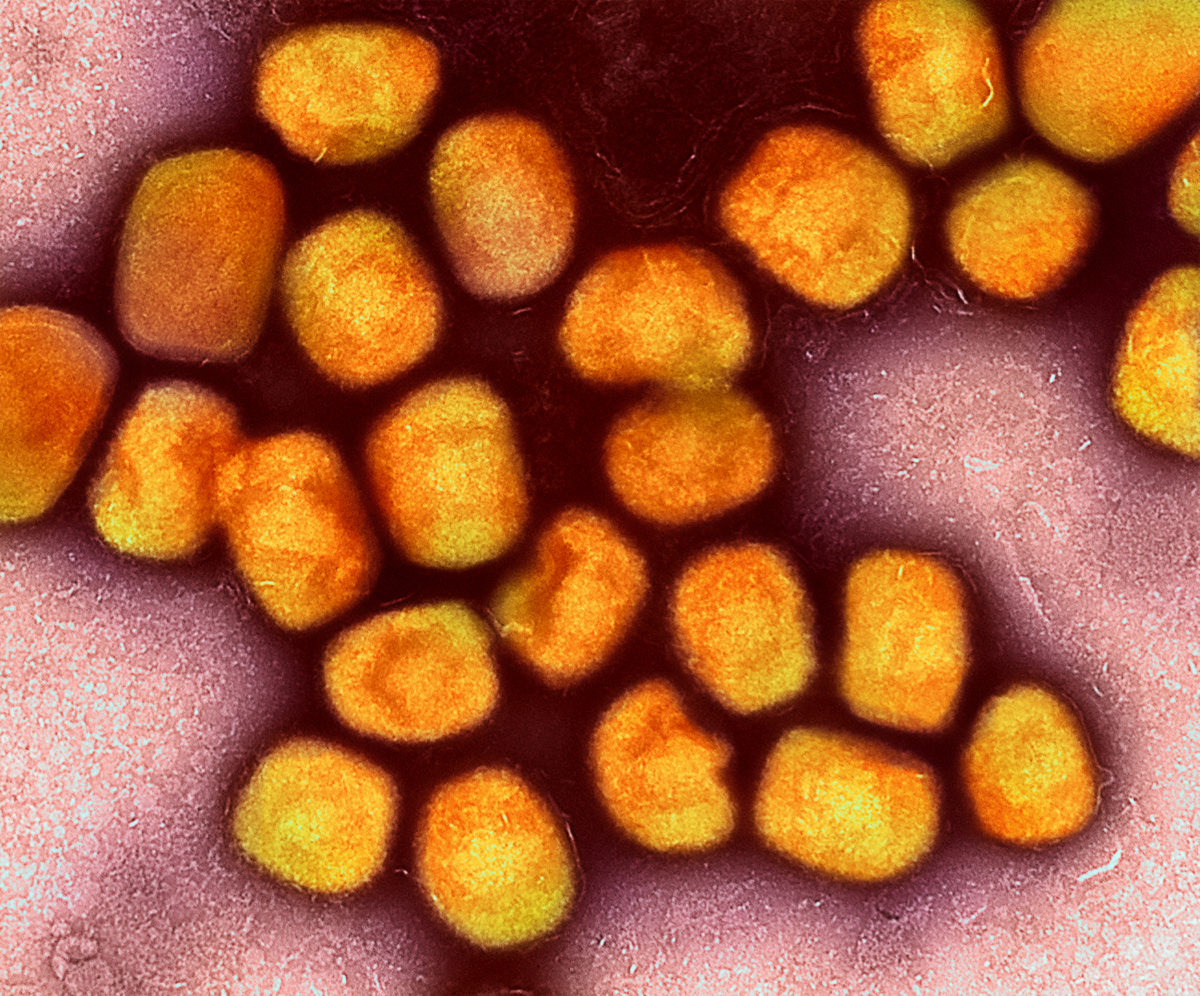

(Photo: Colorized transmission electron micrograph of monkeypox virus particles (gold) cultivated and purified from cell culture. Credit: NIAID via Flickr; CC BY 2.0)

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO, please send updates on how you are working in this crisis to tanya.gulliver-garcia@disasterphilanthropy.org.

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Donor recommendations

If you are a donor looking for recommendations on how to help in this crisis, please email regine.webster@disasterphilanthropy.org.

More ways to help

Philanthropic contributions to mpox were low with only two major grants issued by pharmaceutical companies. A recent Chronicle of Philanthropy article, featured an interview with CDP director of learning and partnerships, Tanya Gulliver-Garcia who stated, “That smaller scale of giving is in stark contrast to the billions of dollars in funding foundations and corporations gave in the early days of Covid-19. By May 2020, grant makers in the United States had given $6 billion in response to the coronavirus spread, according to data from Candid.”

The CDC foundation received $1 million from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Grantmakers in Health, in partnership with Funders Concerned About AIDS and Funders for LGBTQ Issues, hosted a webinar for funders in September to discuss philanthropic needs.

Resources

LGBTQIA+ Communities and Disasters

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+) communities experience the impacts of disasters differently than heterosexual and cisgender individuals.

Pandemics and Infectious Diseases

A pandemic is the sustained transmission of an infectious disease across a wide area of one country or across international borders. Pandemics may be either naturally occurring or the result of human intervention through genetic engineering or biological warfare.

People with Disabilities

When a disaster hits, the lack of inclusion in disaster preparedness – combined with adverse socioeconomic outcomes – creates increased risk and problems for people with disabilities.