Parenting Alone – Single Parents in Disasters

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our “Equity in Disasters” series. The series, which focuses primarily on racial equity and justice issues, also explores how these intersect with other kinds of marginalization and the ways that historical and systemic discrimination create an uneven playing field for recovery. In a previous Equity in Disasters blog, […]

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our “Equity in Disasters” series. The series, which focuses primarily on racial equity and justice issues, also explores how these intersect with other kinds of marginalization and the ways that historical and systemic discrimination create an uneven playing field for recovery.

In a previous Equity in Disasters blog, we explored the notion of intersectionality to understand how various social identities can overlap or intersect and how these relate to systems and structures, particularly institutional dominant structures.

I want to take that concept even further by examining the status of single-parent families, especially single mothers of color, and how disasters affect them.

Compounding disparities and risks

Single mothers, particularly single mothers of color, have a harder time mustering the resources to rebuild after a disaster strikes than a family made of two white parents. This is an example of increased risks because of intersectionality. The risk could be compounded for disabled, lesbian or trans women of color who are also single parents.

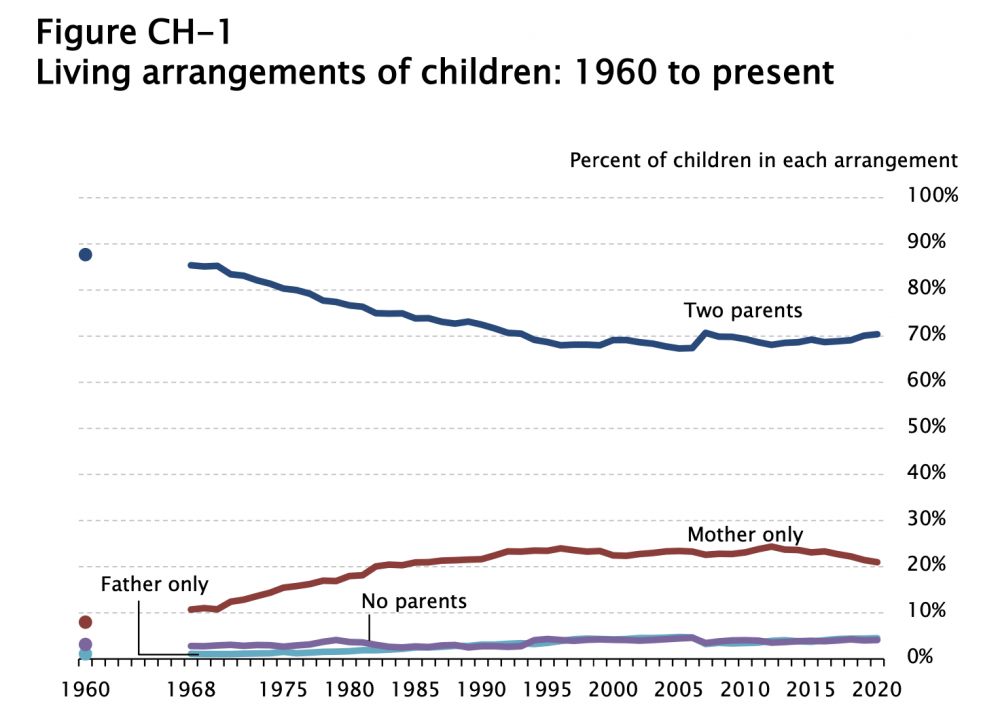

According to the Census Bureau, children under 18 living with two parents still make up the majority of households (69%). However, the number of single-parent families increased between 1960 and 2016 with nearly three times the percentage of children (8% to 23%) living just with their mother and 4% living only with their father (up from 1%). They state, “Of the 11 million families with children under age 18, and no spouse present, the majority are single mothers (8.5 million). Single fathers comprise the remaining 2.5 million single-parent families.”

Systemically, women make less than men (we’ll explore this in even more detail in an upcoming blog on income and equal pay). So, it is no surprise that single fathers tend to have higher incomes and are less likely to be in a crisis-level state of poverty than single mothers. Furthermore, white single parents, just like two-parent white households, have higher incomes and wealth than single-parent households – or even Black or Hispanic double-parent households. Therefore, the intersectionality of family status (single parent versus two parents), gender and race all combine to make households led by a single woman of color more at risk for poverty and post-disaster challenges than other households.

ACT Rochester, an initiative of the Rochester Area Community Foundation, points to the historical discrimination that has created this situation. They say, “Explanations about why more children of color are growing up in single-parent households include the deliberate dismantling of Black families during slavery and its enduring influence on family structure. The high incarceration rates of men of color, economic strain and changing attitudes about marriage also influence these disparities.”

Why we need to check our assumptions in disaster planning

Many programs that help families prepare for a disaster assume that families have the resources to prepare an evacuation kit, or even the supplies needed for a shelter-in-place kit. There is also an overlying assumption in most evacuation planning that families will self-evacuate by personal vehicle. For single moms, especially Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) single moms, this is an economic hardship.

Rebuilding after a disaster is also challenging: Child care and school facilities are not always open, the previous primary residence may not be safe for kids and parents must engage in numerous meetings and activities to get the funding and support needed for rebuilding.

What funders can do

Philanthropy can support disaster preparedness that consider the unique challenges, resource constraints and economic hardships faced by single parents of color, especially single mothers.

Funders also need to recognize the intergenerational trauma caused by racism. They need to fund initiatives that improve incomes and take a trauma-informed care approach to address family stabilization, income growth and decarceration.

Additionally, anti-racism frameworks are an important part of all support programs for single parents, especially mothers. By addressing root cause issues outside of a disaster, funders can help families better cope when disasters strike.

Current advocacy efforts in this area include campaigns for higher (minimum) wages, demands for fair housing and increased child care subsidies.

Of course, it is not solely up to funders to solve poverty among single parents and single mothers of color. We need joint intervention from the government, corporate sector, nonprofit organizations and philanthropy, guided by women of color and other single parents. For its part, philanthropy needs to recognize and address these families’ distinct and unique needs in their grantmaking.

More like this

Housing and insurance gaps hinder disaster recovery