Global Fund for Children

Keeping families together during the pandemic

This story originally appeared on Global Fund for Children’s blog.

In Kathmandu, Asha Nepal has expanded its work on human trafficking to provide emergency support to families struggling amid lockdowns and other COVID-19 restrictions.

Before the coronavirus pandemic struck Nepal, 33-year-old Juna* was well on her way to building a better life for herself and her two teenage children. After experiencing a series of traumas, including being trafficked to India, Juna had received counseling and other support from Asha Nepal, an organization dedicated to preventing human trafficking and caring for survivors. She had found a part-time job at a nonprofit organization and was raising her son while her daughter lived in Asha Nepal’s residential care program.

Shortly before Nepal went into lockdown, however, Juna lost her job. Her depression worsened as COVID-19 restrictions kept her from finding new employment, and she struggled to pay for food.

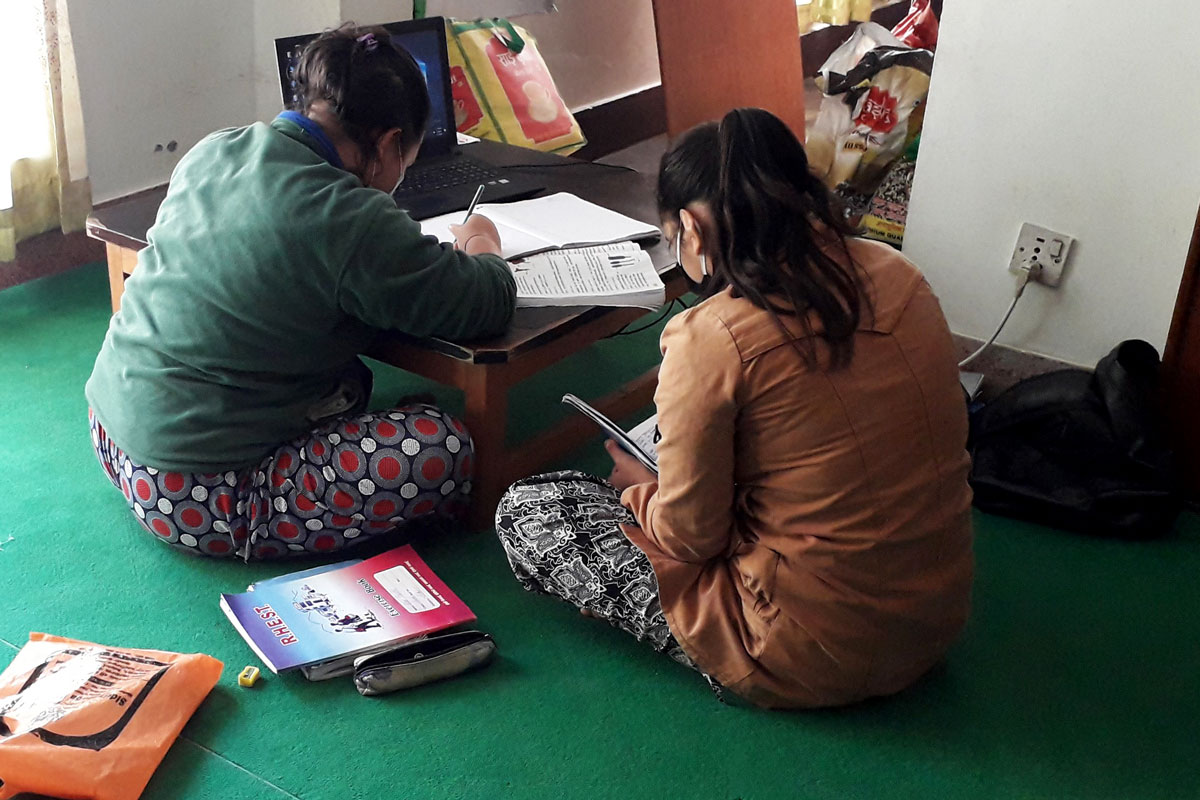

Juna’s family wasn’t the only one struggling. Many of the young people Asha Nepal serves lost their jobs or saw their salaries cut in half during the pandemic. With schools closed, low-income children struggled to access computers and reliable internet in order to attend online classes. Four of the 134 children in Asha Nepal’s programs dropped out of school.

At the same time, the pandemic prevented this Global Fund for Children partner from providing in-person support services. Asha Nepal’s social workers were unable to conduct home visits and had to make do with check-ins over the phone. The organization also had to cancel parenting workshops and suspend the martial arts, computer, and music classes offered at its activities center.

Asha Nepal quickly mobilized to expand its emergency support services, providing food, paying for cooking gas, and covering rent and medical expenses. Its team also stepped in to help families – including Juna’s – obtain government assistance. In addition to delivering food to Juna’s home during lockdown, Asha Nepal provided her with mental health services and helped her get back on her feet.

The organization worries about keeping families together during the pandemic as they grapple with additional stressors.

“For me, the most difficult part is to keep the families intact and strong and living together,” said Kusum Pujari, Asha Nepal’s Administration and Finance Manager.

Much of Asha Nepal’s work centers on preventing young people from being trafficked and on helping survivors reintegrate into the community. More than 61,000 Nepalis – including roughly 10,000 children – have experienced forced labor over the past five years, according to a recent government study. The lack of a social welfare system in Nepal contributes to this problem, according to Asha Nepal, because girls as young as 6 are sent to work to help support their families, which puts them at a higher risk of being physically or sexually abused.

Asha Nepal empowers families with information on child abuse and trafficking and conducts parenting workshops. If a parent is considering moving abroad for work or faces a crisis that could put them at risk of being trafficked, the organization counsels them on the dangers of migrating and helps them address the root causes of the crisis. Asha Nepal also provides scholarships to children to cover educational costs, lessening the economic pressures on low-income parents.

“I think the biggest burden [for families] is providing education to the children, and when we pay fees and when there is no financial burden in the part of children’s education, the families are more stable,” said Smriti Khadka, Asha Nepal’s General Secretary.

Asha Nepal also supports child survivors of sex trafficking and forced labor, providing trauma and career counseling, healthcare services, and other assistance. When it’s not possible to safely reintegrate a survivor back into the community, Asha Nepal cares for them in family group homes in which “house mothers” hired from the local community take care of small groups of children. This family-based model allows Asha Nepal to ensure that each child receives individualized care, and also increases the community’s acceptance of the children.

Gia*, a single mother and one of the beneficiaries of Asha Nepal’s programs, said the organization has helped her develop self-confidence. “Before, I used to feel scared,” she said. “Now, I have the backup of Asha Nepal – I have built my confidence and I feel I can do anything now.”

For Smriti and the rest of the Asha Nepal team, seeing a child succeed in school is the most rewarding aspect of their work.

“When we see this child doing something like complete high school or enroll in college or university, and they start earning and supporting their family, that’s the best part,” Smriti said. “We believe that education can change their life. Not only their life, but through them, they can change a whole family’s life, and that is happening.”

Some graduates even return to Asha Nepal to ask how they can help the organization.

“When they become independent, they have a gratitude kind of attitude,” said Project Coordinator Uzen Malla. “Some of them come and share that they want to spend some of their earnings for Asha Nepal.”

Despite all of the obstacles Juna and her family have faced over the past year, Juna’s 16-year-old son graduated from high school in August 2020 and is currently earning a diploma in computer engineering. He’s now well on his way to a brighter future.

Using an emergency grant from GFC, supported by the Center for Disaster Philanthropy’s COVID-19 Response Fund, Asha Nepal plans to further expand its emergency support services and, if schools remain closed, to buy smartphones that children can use to take classes online.

Learn more about how GFC is supporting children affected by the coronavirus – and how you can help.

*Names have been changed to protect the identities of program participants.