Intersectionality in Disasters

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our “Equity in Disasters” series. The series, which focuses primarily on racial equity and justice issues, also explores how these intersect with other kinds of marginalization and the ways that systemic discrimination creates an uneven playing field for recovery. Everyone is vulnerable to a disaster, but it is […]

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our “Equity in Disasters” series. The series, which focuses primarily on racial equity and justice issues, also explores how these intersect with other kinds of marginalization and the ways that systemic discrimination creates an uneven playing field for recovery.

Everyone is vulnerable to a disaster, but it is increasingly evident that some people, groups and communities are more at risk of serious negative impacts than others.

In a 1982 speech about learning from the 60s, Audre Lorde said, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” Disasters amplify how these interconnected identities and issues can affect outcomes and the prospect of full recovery.

More “isms,” more risks

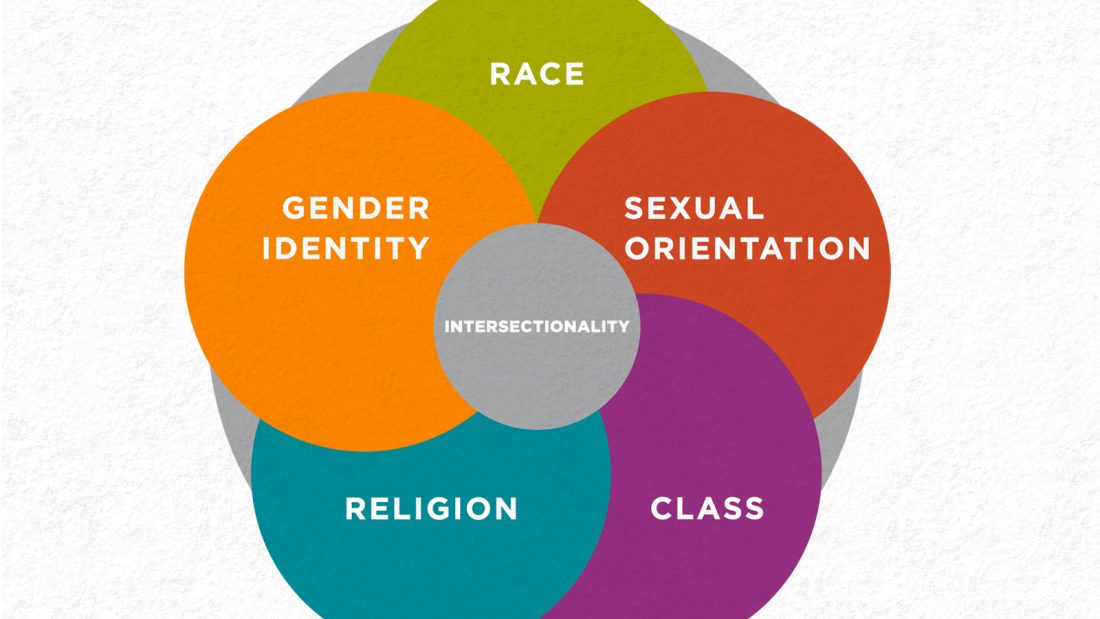

Think about your own life and the way you identify like a circle. Now take that circle and divide it like pie slices, each portion correlating to pieces of your identity. Some aspects may offer you power and privilege in society, whereas others may be areas in which you face oppression.

For example, I’m a white middle-class, fully employed Canadian with a master’s degree. I speak English as a first language (and am conversant with others) and have stable housing. These are all privileges that intersect to help me in my life, even during crises such as disasters.

However, I’m also a fat, queer, disabled, immigrant woman. Although my privileges, especially my race, tend to overcome the oppression I’ve faced, I have been stereotyped or discriminated against because of these identities. I have lost job opportunities, relationships and family, and had challenges accessing services. I can’t vote and am often unable to carry out certain tasks or activities. But I’ve been very fortunate because none of the areas of inequity in my life have caused me any issues in disasters. And as a resident of New Orleans, I’ve seen more than my fair share.

The higher the number of “isms” you face (i.e., racism, sexism, ageism), the higher your risks before, during and after a disaster. When you have fewer areas of vulnerability, it is more likely that you will have lower risks and more resources to help you evacuate and recover. Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw calls this notion of combined vulnerabilities “intersectionality.”

Similar to Lorde, Crenshaw says intersectionality is “a lens, a prism, for seeing the way in which various forms of inequality often operate together and exacerbate each other. We tend to talk about race inequality as separate from inequality based on gender, class, sexuality or immigrant status. What’s often missing is how some people are subject to all of these, and the experience is not just the sum of its parts.”

Either Black or woman, but not both

As a lawyer and law professor at UCLA in the 1980s, Crenshaw wanted a concept that was easy to understand during various court battles. She told New Statesman America, “I wanted to come up with a common everyday metaphor that people could use to say: ‘it’s well and good for me to understand the kind of discriminations that occur along this avenue, along this axis – but what happens when it flows into another axis, another avenue?’”

She developed her theory to highlight how Black women face compounded discrimination because they experience both racism and sexism simultaneously. She represented five Black women who sued General Motors (Degraffenreid vs General Motors) for bias due to race and sex in hiring and layoffs.

While General Motors hired Black men to work in the assembly lines and white women to work in the cushion room, no Black woman – save one janitor – was hired to work in either area until 1970. When the company laid off workers, the “last hired, first fired” policy meant Black women experienced disproportionate layoffs. The women claimed that because they hadn’t been allowed to work in the assembly line (no woman was) and they weren’t hired to work in the sewing room, GM prevented them from gaining seniority.

The women lost their case because there was no protection against dual discrimination. The courts said, “If the women had been able to show that they had been victims of discrimination because they were black or because they were women they would have had a case, but because GM was not discriminatory against white women nor black men, the women had no legal case.”

Crenshaw created intersectionality to, “capture the applicability of black feminism to anti-discrimination law. The particular challenge in the law was one that was grounded in the fact that anti-discrimination law looks at race and gender separately. The consequence of that is when African American women or any other women of colour experience either compound or overlapping discrimination, the law initially just was not there to come to their defence.”

Intersectionality in disasters

So, how does this play out in disasters? When someone is marginalized, they are at higher risk of negative impacts than someone who has power and privilege. But when they experience multiple areas of marginalization, their risk increases exponentially. A Black trans woman will have more issues finding an evacuation shelter than a cisgender, white man. If she does find one, she is more likely to face harassment and negative treatment from other evacuees, staff and volunteers than the man is.

Men and women from racialized communities – with the exception of Asians – make less money than white men and women. While women generally make less money than men, a white woman still makes more money than a Black or Hispanic man or woman. This lowered income means a Hispanic family will struggle more with finding the resources to evacuate or rebuild than a white family.

CDP used to say we focused on “vulnerable people.” However, over the past several years, we’ve realized the importance of explicitly noting that systems and institutions cause vulnerability, more risks and marginalization for specific populations that disasters exacerbate.

What this means for disaster philanthropy

Disaster funding – from philanthropy and government – therefore shouldn’t be equal. Instead, it needs to be based on equity and justice to truly help all people rebuild.

That means funding specialized programs that target services to Black, Indigenous and People of Color or prioritizing them for assistance.

It means providing frontline service workers with culturally competent training so they can account for areas of vulnerability when providing services.

It is increasingly important that those people with multiple areas of risk and vulnerability are given even more enhanced service priority. We need community outreach to reach these populations, especially in times of disaster.

More like this

Housing and insurance gaps hinder disaster recovery