The Politics of Disaster Coverage

Three years ago, the Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report mined the database at the Tyndall Report to investigate how the American public forms its impressions of disasters, both here and abroad, from the news media. That investigation, in 2015, arrived at three main conclusions: The American network newscasts, being American, devote disproportionate attention […]

Three years ago, the Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report mined the database at the Tyndall Report to investigate how the American public forms its impressions of disasters, both here and abroad, from the news media.

That investigation, in 2015, arrived at three main conclusions:

- The American network newscasts, being American, devote disproportionate attention to natural disasters that happen on their home soil rather than internationally.

- Being video news outlets, these newscasts give preference to disasters that are destructive, acute and telegenic, rather than chronic and gradually deteriorating.

- The combination of these two factors means that the hardiest perennial disasters to attract coverage are the domestic storms of the Atlantic hurricane season.

Imagine, then, the sense of vindication when the annual statistics for the 2017 Year in Review were compiled!

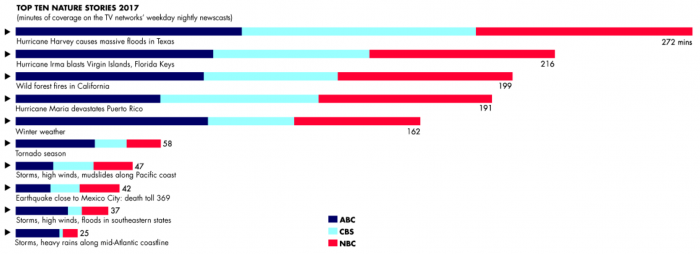

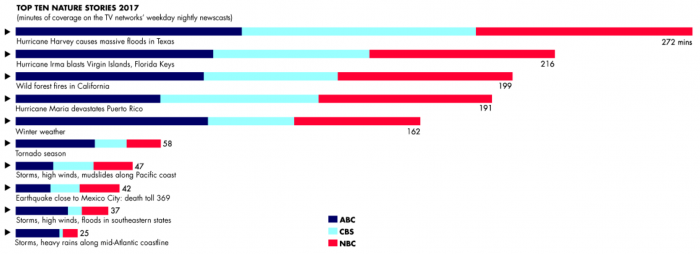

Amid all of the country’s political drama, three of the top ten most heavily covered stories of the year were Atlantic hurricanes: Harvey and its flooding rains around Houston; Irma and its storm track across the Florida Keys; and Maria’s devastating wipeout of Puerto Rico. Not only was each of these storms in the year’s top ten, the volume of coverage they attracted placed them among the top ten hurricanes in the Tyndall Report’s entire three-decade-long data series.

Of course, it is impossible to banish politics altogether from these disaster stories. For example, back in 2005, the massive coverage triggered by Hurricane Katrina eventually spread from disaster pure and simple to questions concerning the competence—or lack thereof—of the Army Corps of Engineers and the protections—or lack thereof—for poor, urban, African-American populations. To a lesser extent in 2017, the inundation created by Hurricane Harvey in Houston and its suburbs eventually led to questions concerning the city’s rapid, unregulated, sprawl and the urban necessities of zoning, reservoir planning and unpaved parkland.

The parallel with Katrina is yet more instructive when it comes to Hurricane Maria. When the final death toll is eventually counted, it may be that the consequences of the months-long electricity outage throughout the rural heartland of the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico will turn out to be just as fatal as the floods that wiped out the poor neighborhoods of New Orleans. And just as Katrina created a mass migration of flooded Louisianans to Texas, Maria prompted an exodus of powerless Puertoriquenos to Florida.

Yet the minutes of coverage devoted to Maria (186 on all three newscasts combined) were not even as many as those accorded to Harvey (272) and Irma (216), let alone the massive coverage devoted to Katrina (1153) in the year of that disaster.

It turns out that our initial conclusions from our 2015 investigation need a slight tweak.

First, let’s not forget the obvious. Novelty is a key component of newsworthiness. The fact that Maria was the third major hurricane of the season meant that much of its drama was by that time no longer shocking but repetitiously redundant.

Second, the equation of hurricanes with “acute and telegenic” disasters compared with those that are “chronic and gradually deteriorating” does not neatly apply for Maria, since it was both: the storm was acute, while the power blackout was chronic. Since the death toll was largely the fault of the latter, the seriousness of the disaster was not reflected in its coverage.

Third, it is not enough to state that “American” disasters attract disproportionate attention. Puerto Rico was not treated as fully American by the American broadcast networks. Instead, it was treated as non-American in that it is not on the mainland and therefore harder to reach; non-American in that it is Spanish speaking and therefore traditionally covered by Univision and Telemundo, not ABC-CBS-NBC; and crucially, non-American in that its citizens are second-class, denied full and equal representation in the halls of Congress—thereby rendering impotent political demands for a vigorous federal response.

Its colonial status was part of the reason why the island’s electricity grid was underdeveloped and vulnerable in the first place. Once disaster struck, its colonial status was part of the reason its fatal consequences were not treated by the mainstream media with the attention that fully-fledged, English-speaking, American citizens on the mainland would automatically expect.

So the news of 2017 serves as a useful reminder: headline-grabbing disasters are still political phenomena, even when the prominence they achieve in the news agenda is apparently a respite from contentious politics.

More like this

What’s Happening with the 2017 Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund