UN IASC Cluster Approach

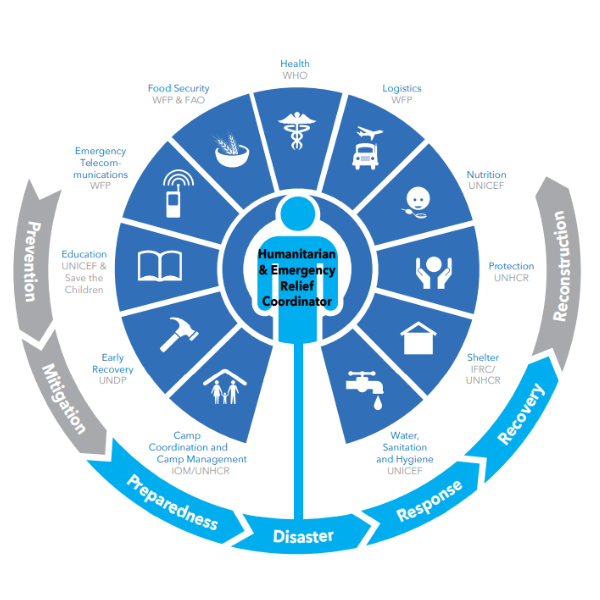

The United Nations uses a multi-pronged Cluster Approach to coordinate humanitarian and emergency relief for disasters. Clusters are groups of humanitarian organizations in each of the main sectors of humanitarian action. They are designated by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee and have clear responsibilities for coordination.

Overview

The coordination of humanitarian and disaster response activities is valuable, not only to avoid duplication of services but also to prioritize, agree on and promote best practices and better maximize resources.

The cluster approach for coordination of response activities around specific thematic and sectoral groupings was initiated on Sept. 12, 2005, in response to the Humanitarian Response Review commissioned by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA) following the Kashmir earthquake in Pakistan. Since then, this approach has been deployed to help coordinate humanitarian responses in more than 60 countries.

While various agencies in the United Nations (UN) system serve as coordination focal points for different humanitarian sectors in emergency response, they should never be assumed or expected to direct or govern the activities of humanitarian agencies. To do so could violate neutrality, impartiality and independence, values that humanitarian agencies consider to be of paramount importance. Coordination is voluntary and, for this reason, can easily be undermined through lack of participation.

The United Nations Cluster System, managed at the global scale by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) Global Cluster Coordination Group, is the key means for participatory humanitarian coordination. Cluster meetings are open to all, and the agenda is generally to identify unmet needs and reduce gaps in response, increase the efficiency and effectiveness of humanitarian response actors’ activities, develop and provide technical guidance and standards, and facilitate an information sharing and decision-making forum for participants.

Cluster membership is largely composed of UN agencies and international nongovernment organizations (INGOs).

The cluster approach functions at two levels. At the global level, the aim is to strengthen humanitarian standards by increasing technical and human capacity. At the country level, the primary purpose of the cluster is to strengthen coordination between all humanitarian organizations active in a particular crisis.

There are currently 11 global clusters, each coordinated by a Global Cluster Lead Agency (GCLA).

| Cluster | Global Cluster Lead Agency |

|---|---|

| Camp Coordination & Management | UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) (conflict) and International Organisation for Migration (IOM) (disaster) |

| Early Recovery | UN Development Programme (UNDP) |

| Education | UN Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and Save the Children |

| Emergency Shelter | UNHCR (conflict) and International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) (disaster) |

| Emergency Telecommunications | World Food Programme (WFP) |

| Food Security | WFP and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) |

| Health | World Health Organization (WHO) |

| Logistics | WFP |

| Nutrition | UNICEF |

| Water, Sanitation and Hygiene | UNICEF |

| Protection (Child protection; gender-based violence; land, housing and property; mine action; rule of law and justice) | UNHCR, UNICEF, UN Population Fund (UNFPA), UN Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), UN Mine Action Service (UNMAS), UNDP |

The UN humanitarian coordination architecture consists of seven key roles.

- UNOCHA supports inter-cluster coordination to ensure the development and implementation of common strategies, the integration of crosscutting issues, and the implementation of agreed strategies. UNOCHA also serves as the secretariat for inter-agency coordination mechanisms such as the IASC.

- The Inter-Agency Standing Committee (IASC) is an inter-agency forum for coordination, policy development and decision-making that includes the key UN and non-UN humanitarian partners.The committee develops policies, determines responsibilities, identifies and addresses gaps, and advocates for the effective application of humanitarian principles.

- The Resident/Humanitarian Coordinator (RC/HC) sits at the country level and provides leadership and coordination to ensure appropriate and effective humanitarian action. The RC/HC establishes and convenes the Humanitarian Country Team (HCT). The HC has a fundamental strategic leadership role in all areas of cluster coordination and meets with Cluster Leads regularly.

- The Humanitarian Country Team (HCT) sets policy, resolves issues and advises the RC/HC. The HCT is considered the ultimate platform for decision-making and coordination of humanitarian action for a specific country or response. The HCT is headed by the RC/HC and comprises Heads of UN agencies and representatives from the NGOs and the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement. Heads of agencies who also lead Clusters represent their agency and Clusters in this forum.

- Inter-cluster Coordination Groups (ICCG) ensure technical and operational collaboration between clusters. The ICCG is headed by an Inter-Cluster Coordinator (usually UNOCHA) appointed by the RC/HC.

- Global Cluster Lead Agency (GCLA): A GCLA is responsible for the operation of a cluster at the global level. They strengthen cluster preparedness, develop and refine cluster policy, and build cluster response capacity at all levels before a crisis by improving technical expertise, overseeing resource stockpiling and establishing standby teams.

- Cluster Lead Agency (CLA): A CLA is directly responsible for the operation of a cluster at the country level. They are accountable to the RC/HC and expected to mobilize sufficient human, financial, and material resources within their country offices to fulfill their cluster obligations.

Key Facts

- The IASC Cluster System functions broadly in seven ways. The UN’s Humanitarian Coordinator (HC) may (1) activate relevant clusters in response to a crisis event at the country level, particularly when the local government’s capacity to respond is overwhelmed, along with (2) mobilizing the lead agencies responsible for (3) coordinating each cluster. Critical (4) information for coordination is shared within and across clusters, including needs assessment tools and data, response plans, and strategies. Cluster coordination also supports (5) resource mobilization by advocating for funding. Accountability (6) for using these resources is enhanced through increased transparency, monitoring implementation, clarifying roles, and responsibility and impact evaluations. Activities at the local level are (7) integrated with local and national authorities to ensure that the needs of affected populations are met.

- The Cluster Lead Agency has ten primary responsibilities. Coordination mechanisms and inclusion of all stakeholders; coordination with national authorities and other local actors; needs assessment and analysis, including gap identification; strategy development and planning, contingency planning and preparedness; application of standards; training and capacity building; monitoring and reporting; advocacy and resource mobilization, including reporting; and being the provider of last resort. The term “provider of last resort” means a commitment by the Cluster Lead Agency to do the utmost to ensure an adequate and appropriate response.

- Effective cluster coordination can realize an impact greater than the sum of its parts. During an emergency response, the process of coordination should rapidly progress from simply information sharing on needs identified and activities delivered to direct collaboration and partnership between cluster members. Effective coordination implies active participation of all stakeholders in cluster meetings, sharing of information and dedicated reporting of implementation activities. Shared strategic approaches allow multiple agencies with diverse mandates to achieve goals collectively that could not be achieved by individual approaches alone. Clusters are the expression of that collective realization and aim to provide the “enabling environment” that allows diversity to strengthen both the effectiveness and efficiency of aid delivery.

- Most humanitarian actors engage in three key areas of coordination. Actors collectively agree on a strategic, operational framework that outlines the overall emergency response approach while allowing for diversity in program orientation. Also, timely sharing of reliable and relevant data for actors to adapt ongoing programs to the evolving needs and priorities of the local affected population and other stakeholders. Lastly, actors develop, formulate and share the most appropriate technical guidance and practices (e.g., culturally and contextually relevant treatment protocols for a disease outbreak or epidemic, or standard shelter designs that may be earthquake resistant and respect cultural norms and traditions). However, participation is voluntary.

How to Help

- Where possible, attend cluster coordination meetings. Many cluster coordination meetings at the country level are offered virtually and in person. Attending these can be invaluable and give a real sense of the tone, tenor and urgency of various needs and funding gaps. Additionally, since engagement in clusters is voluntary, attending meetings can be a way to identify humanitarian actors who are earnestly engaged in coordinating their relief efforts.

- Prioritize funding organizations that are active locally and demonstrate direct, regular, meaningful participation in relevant official coordination mechanisms and meetings such as clusters. As a general rule of thumb, we advise against funding activities that have not been approved in response plans and coordinated through coordination mechanisms such as clusters or working groups. Locally-led humanitarian response is widely regarded as more effective, more efficient and more likely to improve accountability to and participation of those most affected by disasters and crises, but these organizations are regularly underfunded.

- Consider funding in-country coordinator roles that are traditionally difficult to sustainably fund. Engagement and participation in cluster coordination, particularly in the early, acute days and weeks of a humanitarian emergency, is difficult to fund and consistently achieve for some NGOs, particularly local organizations, with smaller administrative and staffing budgets. In addition to funding challenges, many local and smaller organizations lack access to clusters. Funders can help by supporting cluster engagement roles for these types of organizations that strengthen capacity while ensuring access.

- Consider funding inclusion adviser positions (representing specific marginalized groups). Such positions may sit within clusters and/or the coordination of inter-sectoral working groups that work across clusters, such as Age and Disability Technical Working Groups or Inclusion Task Forces. While these roles are not part of the formal cluster system, their role is to work across the entire response architecture, ensuring that the unique needs of specific historically marginalized populations are identified, planned for and included in formal response plans.

- Regularly consult cluster resources and incorporate that information into funding analyses and decisions. In addition to offering virtual and in-person access to cluster coordination meetings, the CLAs post meeting minutes and any reporting documentation to the cluster website or ReliefWeb within days of each meeting. These documents offer a wealth of information to donors that can help inform needs and funding gap analyses and decisions.

- Look for ways to leverage country-based pooled funds (CBPFs). These funds are established when an emergency occurs or when an existing crisis worsens. Contributions to the funds are collected into a single fund to support “high-priority” projects. Global Guidelines set out the minimum global standards for effective and efficient management of CBPFs.

- Consider helping to fund the UN’s Central Emergency Response Fund (CERF). The CERF is continuously managed by UNOCHA at the global level to ensure that humanitarian aid reaches affected populations quickly and effectively in the early stages of a crisis. It aims to address funding gaps and enable timely responses to unforeseen emergencies. It is particularly crucial in mobilizing initial responses and providing bridge funding in situations where traditional funding mechanisms may take longer to mobilize resources.

What Funders Are Doing

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) has supported partners’ efforts to engage with and strengthen coordination in complex humanitarian emergencies through its various funds.

- CDP provided $872,336 to HelpAge USA in 2022 to improve the lives of older people by funding specific inclusion advisor positions focused on influencing the UN-led international humanitarian system (at the Geneva cluster coordination level) and four country-led systems (spanning various clusters) to be more inclusive of older people. The grant also strengthened capacity and empowered UN and NGO humanitarian actors in Ukraine, Moldova, Ethiopia and Venezuela to deliver age-inclusive humanitarian responses and ensure the participation of older people.

- CDP provided $491,000 to OutRight International in 2022 to fund two positions to advocate for broader inclusion of LGBTQIA+ needs in Ukraine and globally. The increased capacity will focus on providing a bridge between national and international actors, identifying needs, ensuring representation in decision-making and coordinating with humanitarian and civil society actors. The grant made it possible for the first time for a dedicated LGBTQIA+ inclusion advisor to be deployed to work within the UN-led humanitarian system.

- CDP provided $485,000 to the Organization for Refugee, Asylum and Migration (ORAM) in 2023 to build the capacity of INGOs, NGOs and civil society organizations working with LGBTQIA+ refugees and displaced people to provide tools to meet the unique needs of this population in Europe and Kenya. The grant is designed to complement the work of OutRight International in Ukraine.

Learn More

- Global Humanitarian Assistance Report 2023

- Global Humanitarian Overview 2024

- Global Camp Coordination and Camp Management Cluster

- Global Cluster for Early Recovery

- Global Education Cluster

- Global Emergency Telecommunications Cluster

- Global Food Security Cluster

- Global Health Cluster

- Global Logistics Cluster

- Global Nutrition Cluster

- Global Protection Cluster

- Global Shelter Cluster

- Global Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) Cluster

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.