Localization

Disaster Phases

Indigenous Peoples

Philanthropy and COVID-19: Examining two years of giving

Chemical Emergencies

Overview

A chemical emergency involves the discharge or release of hazardous liquids, gases or solids. It can happen as a result of an industrial accident, failed infrastructure or an intentional attack. Anywhere hazardous products are manufactured, transported or stored can potentially be the site of a chemical release. The risks associated with a chemical release include explosions, poisoning and environmental contamination. This insight will focus primarily on the human health and environmental concerns related to a chemical emergency.

In every situation involving a chemical release, human activity creates the risk – whether through manufacturing, transportation or storage. As a result, it is essential to recognize that the ability to mitigate the risk associated with chemical release lies solely with humans, unlike the risk associated with many other types of disasters.

In many situations, the manufacturing of chemicals – whether the creation of new ones or refining one into another – involves more than just those specific materials. Many processes rely on additional chemicals as part of the manufacturing or refining process. For example, the process of extracting gold requires sodium cyanide, zinc and sulfuric acid, each toxic in the right amounts. After Hurricane Harvey, a refinery belonging to Valero Energy released the toxic gas benzene from a ruptured tank. Health officials measured benzene concentrations of up to 324 parts per billion – higher than the level at which special breathing equipment is required for people working with benzene. The highest concentrations were found in the Manchester area of Houston, a neighborhood composed of 98% people of color, primarily Black and Hispanic residents.

Chemicals require specialized storage and transportation equipment to ensure they are safe and secure through their entire life cycle. Releases during storage can happen when infrastructure fails, when containment systems are not appropriately maintained or when mistakes or deliberate omissions occur during procedures. Transportation accidents such as train derailments or motor vehicle collisions can often cause an emergency when transportation containers are breached during the incident.

Key Facts

- Chemical emergencies are often more deadly and affect more people than other types of disasters. Because many chemicals are usually stored or transported as liquids or gases, their release can be much more severe than the release of something stored as a solid. For example, in 2016, a truck carrying 63 drums of yellowcake uranium rolled over in Saskatchewan, Canada. The contamination from this incident was minor and localized because it was a solid substance that did not spread very far. In comparison, when the 2011 tsunami hit the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor, its radiation spread across the Pacific Ocean because it was released in both gas and liquid forms.

- Many of the “worst” disasters in history are the result of chemical releases. Because they can be so deadly and affect such a wide swath of people, animals and the environment, chemical releases are often high on the list of “worst” disasters. The Exxon Valdez and Deepwater Horizon oil spills are examples of large-scale chemical releases during extraction and transportation. In 2020, an inappropriately maintained storage container at a facility on the outskirts of Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India released a cloud of styrene vapor across a 1.9 mile (3 kilometers) region, ultimately killing 11 and injuring more than 1,000 people. When the Union Carbide pesticide plant in Bhopal, India released a chemical catalyst used in manufacturing pesticides in 1984, as many as 16,000 died and more than 500,000 people were injured.

- Racial and economic inequity is a significant indicator of risk from a chemical emergency. Many neighborhoods and communities at the highest risk of experiencing a chemical release are historically racially segregated or home to people living in poverty. When chemical manufacturing plants moved into the area around Reserve, Louisiana, the community quickly shifted from a majority-white to a majority-Black community. Reserve is now part of Chemical Alley, which is disproportionately Black and poor. The same is true of major transportation corridors. Communities living along major rail corridors or roadways are often composed of Black and/or impoverished communities. According to the NAACP, race is the leading indicator for the placement of toxic facilities in the United States.

- Governments are often left to clean up chemical releases when the companies who create them abdicate their responsibilities. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is responsible for cleaning up 40,000 contaminated sites – known as Superfund sites – across the U.S., including more than 1,300 deemed to be a priority based on their risk to human and environmental health. Although every attempt is made to have the company responsible for the chemical release pay, approximately 30% of these sites – often the most heavily contaminated – are funded solely by the U.S. government through taxes.

How to Help

- Support affordable housing in neighborhoods away from industrial areas. Many communities in and around industrial areas with a high risk of chemical release are disproportionately impoverished and racialized compared to other neighborhoods. Increasing the availability of new affordable housing in safe locations will allow people to move into lower-risk areas.

- Help fund preparedness efforts and resilient infrastructure in areas at risk of a chemical release. A chemical release can happen at any time and without any warning. People need to be prepared in the event of an evacuation or shelter-in-place warning. This includes having access to running water, electricity, communications and internet if they need to shelter-in-place for an extended period. In the event of an evacuation, there may be little or no warning, so people need to be prepared for an extended absence away from home at a moment’s notice.

- Fund research into safer modes of transportation and storage. The impacts of a chemical emergency are so significant that it is more cost-effective to prevent a chemical release from ever happening. Research that focuses on safe ways of transporting and storing chemicals will reduce the risk of a disaster ever happening, making more money and resources available for other emergencies and disasters.

- Oppose gerrymandering and support the development of independent electoral boundary bodies. Gerrymandering is extremely common, particularly in ways that benefit wealthy white elected representatives. As a result, many electoral divisions, such as Houston’s Manchester neighborhood, are unequally represented because their boundaries are drawn according to the chances of re-election and not based on demographics or even geography. Areas that are badly in need of representation often have their voices drowned out by the voices of people who have little in common with those who suffer the most from a chemical release.

What Funders Are Doing

- The Annenberg Foundation donated $25,000 in 2017 to Healthy Gulf to monitor the coastal waters of Louisiana and Texas to document oil and chemical spills and hold industry accountable for the impacts of those spills.

- After the 2013 train derailment, chemical release and explosion in Lac Mégantique, Quebec, donors from around the world, including a $47,000 donation from the Lions Club, helped re-open the local library with donations equaling more than 200,000 books and other media.

- In the wake of the Deepwater Horizon spill, the Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors gave $4 million to the Gulf Coast Community Foundation for community aid in 2011.

- In 2011, the Global Greengrants Fund gave a $3,000 grant to Other Media to help survivors of the Bhopal disaster plan strategic actions to seek justice, rehabilitation and remediation and prevent further contamination of drinking water. Funds monitored the quality of the drinking water delivered to Bhopal survivors, supported environmental youth groups, enabled networking with other affected communities and media coordination.

Learn More

- CDP Issue Insight: Explosions

- U.S. Chemical Safety Board

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Chemical Emergencies Overview

- United States Environmental Protection Agency: Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program

- United States Environmental Protection Agency: TRI for Communities

- EOS.org: Uncontrolled Chemical Releases: A Silent, Growing Threat

- NAACP: In the Eye of the Storm

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Children and Youth

Overview

For children and youth, disasters can take both an emotional and a physical toll, different from how those disasters would affect adults. Young people are not “mini-adults” and their emotional development is still underway. This means they process and understand information differently than their elders.

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) defines children and youth as representing the group of young people from birth to 24 and/or the state at which they obtain independence, whichever comes first. In addition, through the Convention on the Rights of a Child, the UN defines a child “as a person below the age of 18, unless the laws of a particular country set the legal age for adulthood younger.”

The National Center for Disaster Preparedness states, “Children and youth represent a quarter of our population. They are strong and resilient in the face of disasters, often adapting to stresses that weaken most adults, and yet they are also incredibly vulnerable. Young children, in particular, are completely dependent upon many systems in their lives for their survival: their parents, their broader families and communities, the institutions and organizations that care for them and teach them, and the officials and policy-makers who shape their environment.” When a disaster hits or when it is predicted, children need to have a sense of safety. They may hear newscasts and not understand how it is going to affect them. They may feel scared or lost when living in a shelter. They are often separated from all that is familiar including their home – bedroom, stuffed animals, familiar food, technology and daily routines – as well as friends, school and social or recreational outlets. In some cases, they may be separated from family temporarily or for an extended period of time; and they may have lost a loved one during the disaster.

For youth, the impacts are similar, but they may have a more nuanced understanding of the disaster. They may blame their parents/caregivers for not protecting them or their home. Today’s youth are often very politically aware, so they may question the level of — or lack of — response from government and other responders. Youth who were at the point of reaching independence may be frustrated by setbacks – an inability to finish school, the decrease in affordable housing, etc.

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), “children and teens most at risk for emotional distress include those who:

- Survived a previous disaster

- Experienced temporary living arrangements, loss of personal property, and parental unemployment in a disaster

- Lost a loved one or friend involved in a disaster.”

Dr. Irwin Redlener, president and co-founder of the Children’s Health Fund and director of the National Center for Disaster Preparedness at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health and a CDP Advisory Council member, speaks of the importance of “buffering adults.” These adults, parents or others, are able to be key role models and help lessen the blow of catastrophic events. In the immediate term, adults can provide a safety net for children and youth, but as the disaster stretches on – especially when the outcome is catastrophic – the buffering adults may face their own stressors and find it difficult to hide their own emotions.

SAMHSA states, “Most young people simply need additional time to experience their world as a secure place again and receive some emotional support to recover from their distress. The reactions of children and teens to a disaster are strongly influenced by how parents, relatives, teachers, and caregivers respond to the event. They often turn to these individuals for comfort and help. Teachers and other mentors play an especially important role after a disaster or other crisis by reinforcing normal routines to the extent possible, especially if new routines have to be established.”

Key Facts

- Children and youth are not just “little adults”—especially in response to disaster. Developing brains are vulnerable to longer-term impacts in areas such as memory, regulation of emotions and attention. Also, they may be especially affected by trauma because they are less able to anticipate danger and may be less able to articulate how they feel. Children and youth may blame themselves or others for not being able to prevent the disaster and keep them “safe.”

- Generic assumptions cannot be made about the way children or youth will respond to disasters. As with adults, the response to a disaster is uniquely individual. Some young people will have great tolerance and resilience, while others will be more vulnerable and have greater challenges achieving a sense of “normalcy” or even their “new normal”. Factors at play include a young person’s psychological makeup before the event, in addition to the presence or absence of a “buffering adult.”

- Disasters may affect children and youth for years to come. Young people tend to postpone aspects of processing traumatic events until they reach particular developmental stages; they respond age-appropriately, and that response will likely not be a one-time event.

- Culture, economic standing and ethnicity can all play roles in how trauma and recovery are viewed. Vulnerable populations may face insensitivity, limited access to services and additional barriers to receiving the help they need to recover fully.

How to Help

- Support psychological first aid efforts for children, youth and their families. Not enough workers have been trained to effectively help. Mental health providers, in turn, can work with other professionals in health care, schools, spiritual settings and other areas to assist in noticing and treating symptoms of distress. Training should be both developmentally and culturally appropriate.

- Fund age-appropriate preparedness training for children and youth. The best trainings for young people are those that recognize their stage of life and provide information at a level they can best understand. Preparedness for children and youth is a key way of helping them deal with the stress and trauma of a disaster. Many schools, for example, offer hazard-appropriate training for their areas – i.e. tornado or earthquake drills. Additionally, all schools have fire drills and many have incorporated active shooter training.

- Provide school rebuilding and educational supports. The loss of access to a classroom is about more than a loss of education. Schools provide social and recreational activities and they are often community hubs for the delivery of a variety of services. See CDP’s Issue Insight on Education for more information about the importance of educational supports and schools.

- Support services for those already at higher risk for emotional distress, such as those living in violent households. Children and youth already in a vulnerable state will have fewer resources to draw from should a disaster occur.

- Fund studies that will establish best practices in assisting children and youth pre- and post-disaster. Research could be done, for example, on the most effective ways parents, teachers and other adults can be buffers in disaster situations.

- Support the dissemination of evidence-based tools for post-disaster assistance of children, youth and their families. Medical professionals should have plans in place before a disaster occurs.

- Develop and convene leadership that can provide a holistic and collaborative view of clinical, policy, faith-based and other assistance available to communities. Response tends to be siloed rather than networked. The work of CDP’s Midwest Early Recovery Fund’s Midwest Low Attention Disaster Children’s Working Group is an example of how funders and communities can work together to address disaster needs for young people.

What Funders Are Doing

- The Center for Disaster Philanthropy has made several grants to organizations supporting children and youth including:

– Following Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico, ASPIRA,received $300,000 to address food security via three work objectives. They will work to increase the amount of locally grown food, support economic development through tourism activities and develop agriculture and hospitality industry skills in youth ages 12 to 18.

– Texas Children’s Hospital was awarded $779,917, to be spent over two years, for the expansion of the Trauma and Grief Center at Texas Children’s Hospital’s Mobile Unit program. The funding will increase access to best-practice care among traumatized and bereaved children affected by Hurricane Harvey. The Trauma and Grief Center will expand its mobile clinic program to include two units that will provide trauma-informed assessments and care to youth located in the most underserved areas of greater Houston.

– Whole Kids Outreach was able to hire an additional social worker to support children and families affected by the 2017 floods in Van Buren, Missouri. Since this first grant, the Midwest Early Recovery Fund has now made two similar grants. One in nearby Ripley County, Missouri after several suicide attempts by high school students living in another flooded community; the other to support the elementary school in Seeley Lake, Montana after the horrific 2017 wildfire season.

– Additionally, through its Midwest Early Recovery Fund, CDP has supported increased attention to disaster preparedness and response for children and youth. A webinar was held in Dec. 2018 to inform attendees how to support organizations invested in protecting children before, during and after a disaster. The Fund has also launched the Midwest Low Attention Disaster Children’s Working Group to ensure the needs of children are addressed.

- In 2017, Chevron Corporation Contributions Program provided $750,000 to Save the Children Federation in the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey to provide mental health support to 50,000 children in the Houston region affected by Hurricane Harvey through the Journey of Hope program.

- The W.K. Kellogg Foundation gave buildOn $184,161 in 2017 to create a safe learning environment for children in the southwest corridor of Haiti by repairing grantee-constructed schools that were damaged in October 2016 during Hurricane Matthew.

- The Global Fund for Women provided the Philippines’ based group Ranao Women and Children Resource Center a $5,000 grant to offer physical and emotional support to women and girl survivors who are experiencing the effects of the earthquake in San Francisco Surigao City in 2017.

- In 2016, The Ford Foundation provided a $100,000 grant to Mij Film Yapim Reklam Ve Pazarlama Dis Ticaret Ltd. Sirketi for the production of Life on the Road, a documentary made by Kurdish Yezidi youth as they leave refugee camps on the Syrian and Iraqi borders after ISIS is removed from their homelands.

- In 2016, Comic Relief donated $574,936 to The Indigo Trust to support the Sensi Tech Hub in Freetown, Sierra Leone, a new community space where technology and entrepreneurship can interact to create jobs and help give young people opportunities. In the aftermath of a civil war and an Ebola outbreak, many young people in Sierra Leone were unemployed or under-employed. This funding allowed Sensi to give small grants and training to individuals, youth-led start-ups and more established organizations working with young people to help them become more innovative and effective.

- The Irene W. and C.B. Pennington Foundation provided a $30,000 grant following the Great Flood of 2016 to the Baton Rouge Children’s Advocacy Center. They provide licensed therapists to youth and families exposed to trauma and created a group for disaster trauma survivors. They utilize scientifically-based approaches, tapping into the resilience of children so they can shift their life experience of trauma from potential tragedy into growth and being thriving survivors.

Learn More

- SAMHSA: Tips for Talking with and Helping Children and Youth Cope After a Disaster or Traumatic Event: A Guide for Parents, Caregivers, and Teachers

- SAMHSA: Trinka and Sam – The Windy Rainy Day (y en Espa?ol)

- National Center for Disaster Preparedness: Children & Disasters

- U.S. Department of Education: Tips for Helping Students Recovering from Traumatic Events

- Ready.gov: Kids

- Ready.gov: Youth Preparedness

- Children’s Health Fund

- Institute for Congregational Trauma and Growth

- American Psychological Association’s Children and Trauma

- The New York University Child Study Center’s Caring for Kids after Trauma, Disaster and Death: A Guide for Parents and Professionals

- NATO’s Psychosocial Care for People Affected by Disasters and Major Incidents

- The National Child Traumatic Stress Network: How is Early Childhood Trauma Unique?

- Grantmakers in Health’s In Harm’s Way: Aiding Children Exposed to Trauma

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Climate Change

Overview

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “Climate Change refers to any significant change in the measures of climate lasting for an extended period of time. In other words, climate change includes major changes in temperature, precipitation or wind patterns, among other effects, that occur over several decades or longer.”

To prevent confusion, it is important to remember that climate and weather are separate. Climate is the long-term systemic course, while the weather is the daily event. Weather may be variable, but climate will demonstrate long-term trends. Distinguishing these concepts is essential to understand that although weather conditions will vary, the evidence for climate change accumulates over many years. Just because we have record cold temperatures one season does not mean that the Earth is not heating up.

Some climate change happens naturally. Research provided by the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA) shows that there have been seven cycles of glacial advance and retreat in the last 650,000 years. However, the same research shows that atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels have increased exponentially since the Industrial Revolution, and the only possible source is the drastic increase of human activity. This increase in CO2 has caused what is known as the “greenhouse effect” and increased the rate at which the Earth is heating up by trapping heat instead of allowing it to be released into space. It is this increased heat that is causing what is known as anthropogenic (meaning caused by human activity) climate change.

North America is seeing the effects of climate change in many places, including severe and unusual weather patterns, but also in long-term changes to climate. A study released by Science Magazine in April of 2020 drew a direct connection between anthropogenic climate change and the megadrought that affected southwest North America between 2000 and 2018. Increased atmospheric and oceanic temperatures are leading to stronger hurricanes, more rainfall and snowfall, longer wildfire seasons and more frequent droughts. In the winter, increased temperatures are leading to the disruption of the polar vortex, allowing it to break down and send frigid Arctic air into more places more frequently. These same climate changes are happening around the world. In Australia, climate change raised the risk of bushfires by more than 30% in 2019-2020. In 2020, Asia experienced some of the worst monsoons in recorded history. In Russia, record-setting warmth led to hundreds of fires burning through the Siberian wilderness. And in Europe, climate change has contributed to increased drought, heavier rains and flooding and more wildfires.

Key Facts

- Human activity – especially carbon-based emissions – has increased dramatically in the past 70 years. Based on samples taken from ice cores, atmospheric carbon dioxide had never exceeded 300 parts per million. However, readings in 2020 found that the average atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration was more than 400 parts per million.

- The Earth is getting warmer, resulting in additional vulnerabilities – particularly for the elderly and people with disabilities and functional needs. Research by the United Kingdom’s Meteorological Office found that the record-breaking temperatures that country experienced in 2018 were made 30 times more likely – a 3000 percent probability increase because of climate change.

- Indoor temperatures are directly related to increased mortality during heatwaves. Although outdoor temperatures often ease during the evening and overnight hours, extreme heat can be retained inside older buildings and those without air conditioning. As a result, people inside those buildings don’t experience a reprieve from the extreme temperatures, increasing their risk of death. People with disabilities and functional needs, along with those who do not have easy transportation options are also at increased risk because they cannot access cooling centers and other resources.

- We are very quickly reaching the point of no return to prevent or mitigate permanent impacts to our world because of climate change. The United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has warned that the impacts of climate change could be irreversible by as soon as 2030.

- The cost of not acting on climate change could be more than twice the United States’ national debt. A 2015 report by Citigroup, a U.S. banking corporation, found that the cost of not acting on climate change could be as much as $44 trillion by 2060.

How to Help

- Invest in multi-system prevention and mitigation measures. Investing in things like urban forestry, community gardens and natural land preservation not only helps pull carbon out of the atmosphere, they can also help reduce surface heat, feed communities, slow down the passage of water through soil and stabilize the soil around them – reducing the risk of flash flooding.

- Support initiatives to create more resilient critical infrastructure systems. Extreme temperatures can put additional stress on critical infrastructure systems, causing them to fail when they are most badly needed to reduce the impacts of extreme weather.

- Fund projects at the local scale, especially ones that reduce carbon emissions and stabilize indoor temperatures. There are many facilities that would like to add clean power in the form of solar panels or windmills but are unable to afford the upfront cost. There are also many facilities that look after vulnerable populations, which are unable to afford an appropriate Heating, Ventilation and Air Conditioning (HVAC) system.

- Support racial justice, Black Lives Matter and other movements that seek to eliminate inequities in society. Climate change in North America disproportionately affects people in the Black and Indigenous People of Color (BIPOC) community. Climate justice works to embed issues and knowledge from BIPOC communities in the climate change movement. Elizabeth Yeampierre, the co-chair of the Climate Justice Alliance, said this in an interview with Yale Environment 360: “Climate change is the result of a legacy of extraction, of colonialism, of slavery. A lot of times when people talk about environmental justice, they go back to the 1970s or ‘60s. But I think about the slave quarters. I think about people who got the worst food, the worst health care, the worst treatment, and then when freed, were given lands that were eventually surrounded by things like petrochemical industries. The idea of killing black people or indigenous people, all of that has a long, long history that is centered on capitalism and the extraction of our land and our labor in this country. For us, as part of the climate justice movement, to separate those things is impossible. The truth is that the climate justice movement, people of color, indigenous people, have always worked multi-dimensionally because we have to be able to fight on so many different planes.”

What Funders Are Doing

- Through the ongoing Global Recovery Fund, the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) donated $500,000 to the Foundation for Rural & Regional Renewal (FRRR) to support community-initiated and -led projects that support the long-term recovery from Australia’s 2019-2020 Bushfire season that was made much worse because of climate change.

- The Environmental Grantmakers Association (EGA), “works with members and partners to promote effective environmental philanthropy by sharing knowledge, fostering debate, cultivating leadership, facilitating collaboration, and catalyzing action.” They have a number of resources and events available to support Grantmakers.

- Madre donated $70,000 to the Indigenous Information Network in Nairobi, Kenya in 2020 to build the capacity of indigenous women in Kenya to adapt to the impact of climate change through conservation and traditional knowledge exchange. This is a particularly important project because it focuses on the traditional knowledge of Indigenous women, a group of people whose wisdom and insight are often neglected when working to combat climate change.

- In 2018, the Sonoma County Transportation Authority received $1 million from the William and Flora Hewlett Foundation as part of a project to create affordable housing that puts equity, affordability and climate solutions in the center of economic strategy.

- The Walter and Elise Haas Fund provided a $100,000 grant in 2017 to the Center for Popular Democracy’s Hurricane Maria Community Relief and Recovery Fund to help organize support for rebuilding efforts after Hurricane Maria. This fund prioritizes women, people of color and other historically disinvested communities and backs proactive measures to protect Puerto Rico from future climate change-related natural disasters.

- Global Greengrants Fund donated $2,778 to Familias Afectadas Lucia Zenteno in Oaxaca, Mexico to help rebuild homes after the 2017 earthquake to make the homes more resilient towards future earthquakes and to help them shed heat better as a result of the changing climate.

Learn More

- Disaster Philanthropy Playbook: Environment

- CDP Issue Insight: Extreme Heat and Global Warming

- CDP Issue Insight: Wildfires

- CDP Issue Insight: Drought

- CDP Issue Insight: Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

- CDP Issue Insight: Critical Infrastructure

- CDP Issue Insight: People with Disabilities

- CDP Issue Insight: Older Individuals

- NAACP Environmental and Climate Justice Resources

- UN Office for Disaster Risk Reductions: Stop Disasters Game

- World Wildlife Fund: What You Can Do to Fight Climate Change

- UN Sustainable Development Goals: #13 – Take Urgent Action to Combat Climate Change and its Impacts

- Government of New Zealand Ministry for the Environment: What You can Do About Climate Change

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Complex Humanitarian Emergencies

Overview

During political strife or military fighting, innocent populations often are unwittingly involved. The challenges only increase when a disaster occurs or large groups are displaced and need assistance. The delivery of aid can be compromised and relief workers may be put in harm’s way.

Such events are termed Complex Humanitarian Emergencies (CHEs). The United Nations (UN) defines a CHE as “a humanitarian crisis in a country, region, or society where there is total or considerable breakdown of authority resulting from internal or external conflict and which requires an international response that goes beyond the mandate or capacity of any single and/or ongoing UN country program.” In short, CHEs involve an acute emergency layered over ongoing instability. Multiple scenarios can cause CHEs, like the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the man-made political crisis in Venezuela, or the public health crisis in Congo.

CHEs may be worsened by famine and heightened by the outbreak of disease or poor sanitary conditions as people flee their homes due to the fighting as is the case in Syria, in the middle of a civil war and one of the largest refugee crises in the world.

There are two tools responding organizations can use to determine what type of aid is appropriate. For acute CHEs the Multi-Cluster/Sector Rapid Assessment (MIRA) says needs assessment should be “well-coordinated, rapid and repeated/reviewed as necessary to reflect the changing dynamics, drivers and needs in each country and agreed that the results of needs assessments should inform the overall strategic planning and prioritization process.” In a protracted crisis, a Humanitarian Needs Overview (HNO) should follow a MIRA.

In recent years, most CHEs have been caused by intra-country fighting, not as a result of wars between nations. This can bring its own complications. Unraveling a complex humanitarian emergency and providing relief typically requires an understanding of the motivation of the actors involved. In addition, intervention can take on political overtones.

Key Facts

- Groups that are fighting sometimes will not allow humanitarian assistance. Combatants often target civilians, putting them at risk for human rights abuse, food shortages, breakdown of publicly supported health systems and unhealthy living conditions in refugee camps. When conflicts are intra-state, participants do not wear military uniforms, making it difficult to differentiate between combatants and civilians.

- CHEs often bring about Complex Security Environments, situations that cause difficulty for aid workers. In 2018, 171 aid workers were kidnapped, according to Relief Web including 52 kidnappings in South Sudan in the midst of a conflict that began in 2013.

- Conflicts are increasing across the globe. Between 2006 and 2016, the number of political conflicts, which can lead to CHEs, increased from 278 to 402. Also, in 2016, the number of people forcibly displaced reached an unprecedented 65.6 million.

- In the early stages of a CHE, most deaths occur due to diarrheal diseases, respiratory infections, measles or malaria. As the event lingers and people continue to be displaced, the issue often becomes malnutrition.

How to Help

- Provide mental health aid for those affected. People who have been displaced have undergone a significant change in way of life, perhaps including loss of livelihood, extreme poverty and damaged social support structure. Because of the ongoing conflict, they also may suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

- Provide assistance for women and children. These groups often face increased risks in CHEs like gender-based exclusion, marginalization and exploitation.

- Fund research into lessons learned in previous CHEs. Each situation has unique elements, but some lessons may be applied more broadly. The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development published this guidance for evaluating the effectiveness of aid in CHEs. Funding for post-event evaluations would enhance accountability while providing resources that could be adapted for future events.

- Provide assistance for public health needs. With a disaster or ongoing conflict, gains made in public health—immunization, water, sanitation and the like—can be quickly wiped out. Shoring up public health assistance in developing nations and in complex humanitarian emergencies is an area of need. Developing epidemic preparedness protocols could aid public health in a variety of situations, including disasters.

What Funders Are Doing

- The Carnegie Corporation of New York, in 2018, gave $450,000 to the UN’s Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific to foster political dialogue focused on the transition from conflict toward reconstruction in Syria.

- In 2018, the Ford Foundation gave $400,000 to the University of Geneva to strengthen formal and non-formal higher education using blended learning for Syrian refugees in Jordan.

- In 2015, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation gave $800,000 to International Medical Corps to respond to the emergency needs of populations in Yemen affected by the civil war there. The foundation also gave $550,000 to World Vision to provide life-saving and sustaining support to populations most affected by conflict in Syria.

- The Stichting IKEA Foundation gave $42.2 million to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees in 2015 to make refugees and host communities more resilient in Burkina Faso.

Learn More

- Policies to Prevent CHEs

- Environmental Health in Emergencies

- Concepts and Issues in CHEs

- Current Emergencies

- Global Humanitarian Overview

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Critical Infrastructure and Systems

Overview

Critical Infrastructure and Systems (CIS) are the structures people rely on to perform their everyday tasks. They are what keep people, goods and information moving around the world while also keeping people safe and healthy.

During disasters, the continued functioning of all of the Critical Infrastructure and Systems are key to efficient and effective mitigation, response and recovery. When one of the CIS is disrupted, the people who are experiencing the disaster are more likely to have worse outcomes because of the disaster. While each country will have a different set of CIS specific to their jurisdiction, in general CIS are made up of the following sectors:

During disasters, the continued functioning of all of the Critical Infrastructure and Systems are key to efficient and effective mitigation, response and recovery. When one of the CIS is disrupted, the people who are experiencing the disaster are more likely to have worse outcomes because of the disaster. While each country will have a different set of CIS specific to their jurisdiction, in general CIS are made up of the following sectors:

- Health care – This includes not only hospitals and clinics, but also pharmaceuticals, private practitioners, public health, mental health, community-based care and pre-hospital care (first responders).

- Food – This sector is comprised of the production, distribution and preparation of food – including nutrition, agriculture and farming.

- Finance – Banks are the most obvious part of this sector, but this also includes things such as payment processing, private lenders and currency.

- Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) – Water is essential for health and safety, but just as important is the disposal and cleaning of contaminated water and the ability for people to keep themselves clean.

- Information and Communication Technology – The internet, phone lines, data services, cell services and lesser-known technologies such as Industrial Control Systems form the backbone of many systems around the world.

- Safety – Information and Intelligence gathering, law enforcement, the military and fire protection services are all necessary for the safety of people, no matter where they are.

- Energy and Utilities – Along with the electrical system, this sector also includes gasoline and diesel, as well as natural gas. Water is often a public or private utility as well.

- Manufacturing – Every non-natural physical item that exists has to be manufactured in some way, shape or form. This sector includes everything to do with the design and production of physical objects from paper to vehicles.

- Government – Stable government services are necessary to ensure appropriate oversight and regulation of a country’s activities and to negotiate with other countries.

- Transportation – Not only the act of moving people and goods from one point to another, but also the infrastructure necessary for the free movement of people and goods. This includes all modes of transportation including public and private vehicles, trains, planes, boats, buses etc. It also includes the physical infrastructure such as roads, bridges, dams, levees and railroads.

- Shelter – Shelter is key to the short- and long-term safety of people, and this sector includes both Emergency and Interim Shelter as well as long-term housing.

- Education – While education is not often included as critical infrastructure, the lack of education will cause a country or region to lag far behind its neighbors as they advance. Returning students to school is an important part of regaining normalcy post-disaster.

Key Facts

- Critical Infrastructure and Systems (CIS) are key to Disaster Recovery. CIS are key to ensuring people receive the help they need during and immediately after a disaster. Support for any one of these sectors will help speed recovery in every case.

- Pre-Disaster grants in these sectors can make a significant difference. Improving the resiliency of CIS before a disaster happens can help speed up recovery after a disaster by reducing the damage from the event or making it easier to repair and/or replace damaged areas of a CIS sector.

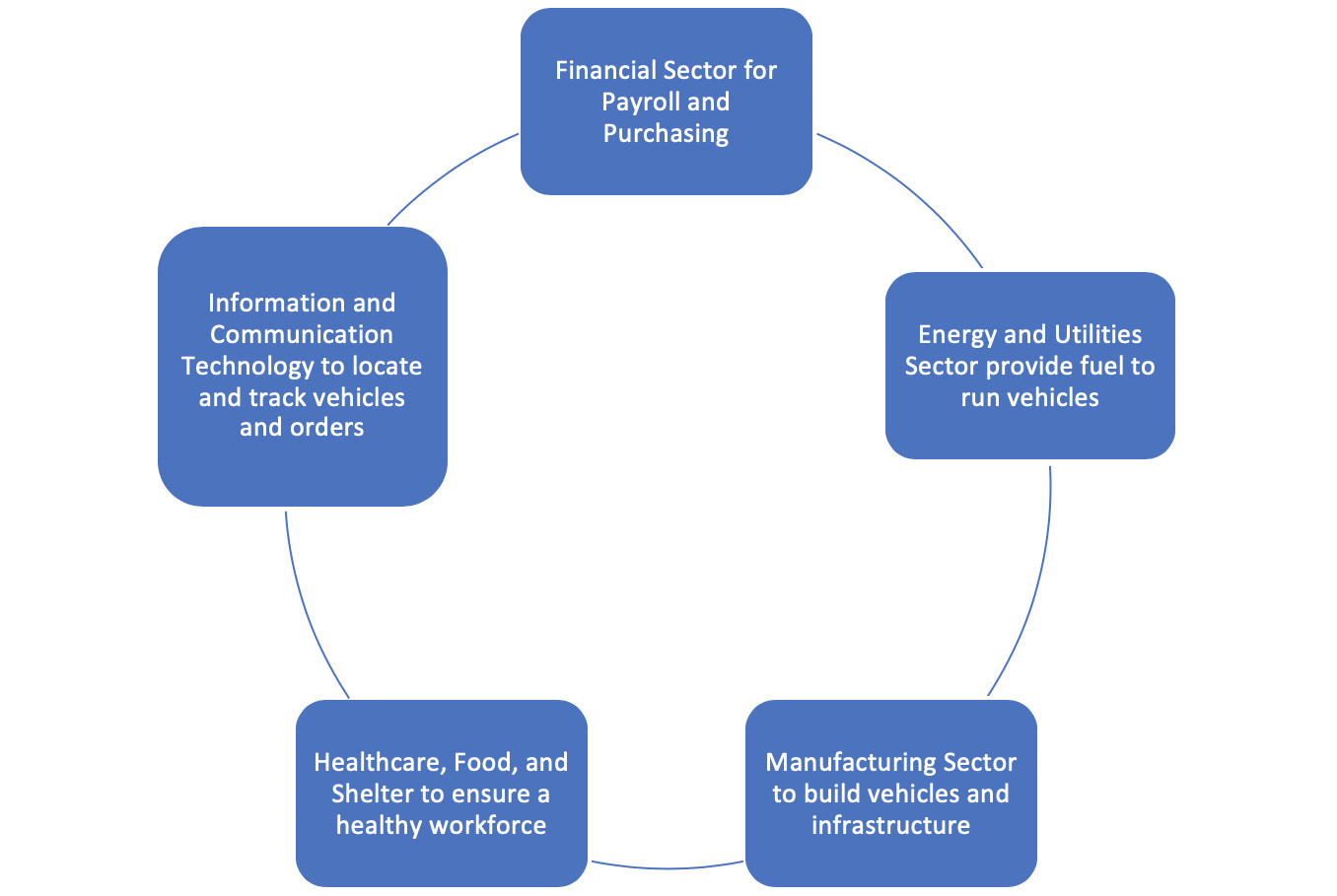

- CIS are all interdependent. Each of the CIS sectors relies on every other CIS sector in order to remain operational, as shown in the simplified diagram of the transportation sector interdependencies. If one CIS sector fails, the others are at an increased risk of failing as well.

- CIS ownership is both public and private. Every country around the world has a combination of both public and private ownership of CIS. The electrical system may be publicly owned, but the manufacturing sector that uses the electrical system is often privately owned. The road system is usually publicly owned, but the vehicles that use the roads are usually privately owned. This mix of public and private ownership can make disaster mitigation, relief and recovery a challenge to fund.

- Rural and tribal communities can benefit the most from effective CIS grants. Rural and tribal communities often struggle financially to build critical infrastructure and will often choose less expensive and less resilient methods of building as a result. Well-structured grants to encourage preparedness and resilience building, as well as grants that encourage the “Build Back Better” philosophy during recovery can make an outsized impact in these communities when compared with larger communities.

How to Help

Funding in any area of critical infrastructure and systems will make a significant impact on the resiliency of people toward disasters. Donors can help by using some of the following principles:

- Fund projects that are publicly-, community- or cooperatively-owned. Critical infrastructure and systems benefit everyone in a community or jurisdiction. Projects that are owned in some way by the people who benefit make them much more accessible and collaborative than privately-owned infrastructure or systems.

- Prioritize grants that enhance infrastructure and systems that support vulnerable and marginalized people. People who are already vulnerable and marginalized are at increased risk when critical infrastructure and systems are damaged or fail. Increasing the resiliency and reducing the restoration time for critical infrastructure and systems means that important resources can be focused on the needs of vulnerable and marginalized people.

- Create unique opportunities to enhance the resiliency of critical infrastructure and systems. The wide variety of sectors contained within the umbrella of critical infrastructure and systems allows for unique loans and funding arrangements. These may include things like low- or no-cost loans for generators or water filtration systems, supporting local food production by funding community gardens or supporting innovative public transit opportunities.

- Participate in local, regional and national critical infrastructure networks. Donors can play an important role in helping to fill gaps in critical infrastructure and systems through their ability to fund projects that may not qualify for other funding. Participating in these networks will help donors understand the needs and locate opportunities to invest in critical infrastructure and systems.

What Funders Are Doing

- The National Community Lottery Fund (formerly the Big Lottery Fund) provided WaterAid with $597,321 in 2012 to respond to the need for climate resilient access to water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services in the Koyra Upazila of Khulna district in Bangladesh. The proposed interventions address three key issues that have exacerbated the impacts of cyclone flooding events in Bangladesh that remain barriers to improving peoples’ long-term welfare.

- In 2018, the NoVo Foundation donated $500,000 to BRAC USA to provide shelter, along with other necessary supports, to Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh with a focus on the needs of adolescent girls.

- The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation gave $150,000 in 2017 to the National Academy of Sciences to provide support to the Forum on Medical and Public Health Preparedness for Disasters and Emergencies.

- In 2017, the Unitarian Universalist Service Committee gave Mouvman Peyizan Papay in Haiti $50,000 to continue construction of a school in the locality of Colladere to serve the victims of the earthquake who live in the Eco-Villages, as well as children from other localities, ultimately helping more kids living in the Eco Village have access to better quality education.

- Also in 2017, the Global Greengrants Fund, Inc. provided $4,000 each to the Tariwa Taro Association and Wan Smol Bag, both in Vanuatu, for unique critical infrastructure projects. Tariwa Taro Assocation used the funds to build food security through education of traditional crop management methods, training new farmers, the creation of a community nursery and the introduction of disease resistant taro seedlings. Wan Smol Bag created a composting public toilet that could be used by people who were experiencing homelessness or did not have regular access to WASH systems. The waste from this toilet is used in local gardens as compost, which also results in increased food security.

Learn More

- The US Department of Homeland Security has many resources related to Critical Infrastructure and Systems.

- There are many cross-border agreements in North America to cooperate on Critical Infrastructure and Systems during emergencies and disasters.

- United Nations University: Five Things You Need to Know About Critical Infrastructures

- EU Science Hub: Critical Infrastructure Protection

- BBC News: Cyber-Attacks ‘Damage” National Infrastructure

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.