Can We Agree to Disagree on Climate and Get Something Done?

Recently when I turned on the television, I got a big surprise: there was Al Roker interviewing President Barack Obama. What? Al Roker, the friendly veteran weather guy from morning news? It turns out that Roker was one of eight weather forecasters who interviewed the President that day as part of a public awareness effort […]

Recently when I turned on the television, I got a big surprise: there was Al Roker interviewing President Barack Obama. What? Al Roker, the friendly veteran weather guy from morning news?

It turns out that Roker was one of eight weather forecasters who interviewed the President that day as part of a public awareness effort to encourage support for the National Climate Assessment.

The assessment, released by the White House on May 7, brought with it a new sense of urgency. The report said, “climate change, once considered an issue for a distant future, has moved firmly into the present. The global climate is changing and is primarily due to human activities, predominantly the burning of fossil fuels.” The report also concluded that “some extreme weather and climate events have increased in recent decades … and threatens human health and well-being in many ways, including through more extreme weather events and wildfire, decreased air quality, and diseases transmitted by insects, food, and water.”

The response from the media was mixed. Here are a few excerpts from the coverage I saw:

The New York Times editorial page read: “The study, produced by scientists from academia, government and the private sector, is the definitive statement of the present and future effects of climate change on the United States. Crippling droughts will become more frequent in drier regions; torrential rains and storm surges will increase in wet regions; sea levels will rise and coral reefs in Hawaii and Florida will die. Readers can pick their own regional catastrophes…”

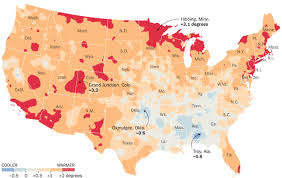

The New York Times news section included a chart comparing average temperatures in the years 1991-2012 to those between 1901-1960 as part of a story on climate change.

USA Today reported 12 of the country’s 47 largest airports are vulnerable to storm surges that are expected to increase from climate change and rising sea levels. Another USA Today story labeled “Miami as the global warming’s ground zero.” It reported American cities most at risk for sea-level rise include New Orleans, Tampa, Virginia Beach and Charleston, S.C.

USA Today reported 12 of the country’s 47 largest airports are vulnerable to storm surges that are expected to increase from climate change and rising sea levels. Another USA Today story labeled “Miami as the global warming’s ground zero.” It reported American cities most at risk for sea-level rise include New Orleans, Tampa, Virginia Beach and Charleston, S.C.

But others pushed back.

The Wall Street Journal editorial page called the assessment “Obama’s Climate Bomb.” It said the “findings of serious empirical climate literature are so obviously exaggerated and colored that the document is best understood as a political tract with a few scientific footnotes. … The irony is that to the extent Mr. Obama’s agenda damages economic growth, he is leaving the country less prepared for climate change.”

A Wall Street Journal news story headline underscored the divisions in our country about climate change: “Obama Climate Push Faces a Lukewarm Public.”

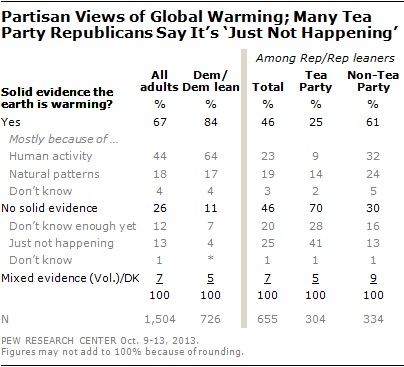

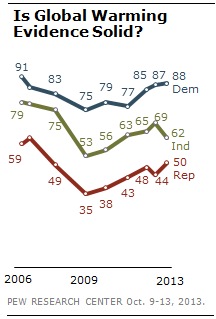

According to a Pew Research study released in November 0f 2013, there are major differences of opinion between Democrats and Republicans regarding climate change.

In fact, during the last eight years, Pew polls have shown little movement among the American public on climate change issues. If anything, there is less support for climate change evidence than there was in 2006.

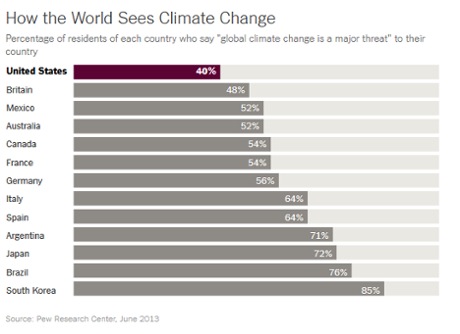

And another Pew study reported that when it comes to climate change Americans are outliers when compared to the rest of the world. Only 40 percent of Americans say global climate change is a major threat.”” That compares to 54 percent in Canada and a whopping 85 percent in Korea.

And another Pew study reported that when it comes to climate change Americans are outliers when compared to the rest of the world. Only 40 percent of Americans say global climate change is a major threat.”” That compares to 54 percent in Canada and a whopping 85 percent in Korea.

So What happens next?

It seems unlikely that we will see any significant legislation passed by Congress during this election season of 2014 concerning climate change or even energy policies in general. And polls suggest that we will continue to have a divided and polarized federal government until at least 2016. Meanwhile, on the international stage it seems equally unlikely to expect any significant action that developed and developing nations can agree upon.

So what happens next? Sitting on the sidelines doing nothing isn’t a responsible choice for those of us involved in natural disasters—and especially not for those us involved in funding disaster recovery

Here are three modest considerations for taking action:

- Start thinking long-term. It’s foolhardy to continue treating philanthropy for natural disasters as emergency one-time experiences. There are not enough private philanthropy resources available to continue on that course and it is an approach that is both unsustainable and ineffective. We need to acknowledge that natural disasters are going to increase in frequency and intensity. Your philanthropic giving strategy needs to reflect this new reality.

- Is your community ready? If more major natural disasters are on the way, what can you do to help your community better plan and prepare? Can you convene donors in your community to develop a common strategy? Can you help your local nonprofits get ready to respond? Can you provide more support to help first responders prepare more effectively? What can you do to support efforts to build a more resilient community?

- Advocacy for building a common strategy. There’s no reason why we need to accept a political stalemate. Natural disasters affect everyone. Surely there are areas of public policy where we can find common ground that is for the benefit of our communities and future generations. Lets support organizations trying to build common ground and common strategies.

- As the authors of an article in Stanford Social Innovation Review recently pointed out, “the days when major foundations could remain above the partisan fray, even as they were deeply engaged in advocating changes in public policy, are all but gone. The polarization of the U.S. political scene is imposing new limits on how foundations can operate in that sphere. But it’s also revealing new ways in which they can influence the policy process.”

More like this