Disasters by the numbers

What are the most expensive disasters, and how much do they cost? What does it mean for philanthropy? CDP's Tanya Gulliver-Garcia explains.

If you think disasters from natural hazards and extreme weather are getting more frequent, you’re right. They are also increasingly expensive.

What are the most expensive disasters, and how much do they cost? And what does it mean for philanthropy? As you read these, remember that these numbers do not include the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has made recovery harder and, in some cases, increased the costs associated with recovery such as food and building supplies.

Disaster costs – insured vs uninsured

The insurance industry does some of the best tracking of global disaster impacts, though with an obvious bias toward insured losses. Munich Re, a global reinsurer, issued a statement in January assessing the 2021 impact of disasters at $280 billion, with about $120 billion of that being insured losses.

That cost is the second-most ever for the insurance sector after 2017, when Hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria helped drive the cost to $146 billion. Last year was also the fourth-costliest year overall from natural hazards and extreme weather events. Munich Re ranked Hurricane Ida as the costliest disaster at $65 billion, of which $36 billion was insured. Next was the European extreme rainfall and floods, which cost $54 billion and was the most expensive natural hazard event ever in Germany.

Swiss Re, another global reinsurer, released its initial summary of the year in mid-December, missing some costly disasters. A full report will likely be issued in March. However, in the December press release, Martin Bertogg, Head of Cat Perils at Swiss Re, said: “In 2021, insured losses from natural disasters again exceeded the previous ten-year average, continuing the trend of an annual 5-6% rise in losses seen in recent decades. It seems to have become the norm that at least one secondary peril event, such as a severe flooding, winter storm or wildfire, each year results in losses of more than USD 10 billion. At the same time, Hurricane Ida is a stark reminder of the threat and loss potential of peak perils. Just one such event hitting densely populated areas can strongly impact the annual losses.”

The secondary perils are a combination of those events that follow a primary peril (fires after earthquakes or floods after hurricanes) and those smaller, usually unnamed natural hazard and extreme weather events, such as blizzards and wildfires.

$1 Billion disasters increase

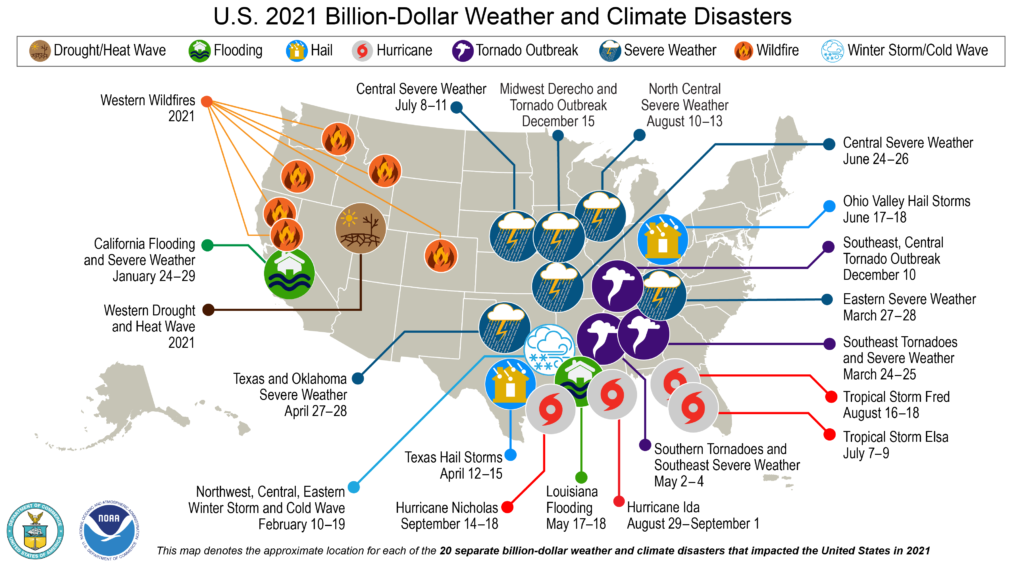

In 2021, the U.S. had a record 20 “billion-dollar disasters,” with the last individual disaster sneaking in on Dec. 15 and a western wildfire starting on the second last day of the year. The National Centers for Environmental Information, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), track these natural hazards and extreme weather events in the U.S. The majority come from secondary perils and cost more and more. In fact, only four of the 20 events received official names: Hurricanes Ida and Nicholas, and Tropical storms Elsa and Fred. Some of the events, e.g., individual wildfires, were named, but are considered part of the larger event of “western wildfires.” While the media may give names to other disasters, they are not part of the official classification that NOAA uses.

In terms of total cost, 2021 was the third-highest year for billion-dollar disasters in the U.S., with an estimated impact of $145 billion. It is behind 2017, which cost $346.1 billion, and 2005 (the year of Hurricanes Katrina, Rita and Wilma), which had a $244.3 billion impact. The four tropical cyclones in 2021 cost $78.5 billion (Hurricane Ida was most of that), followed by the February winter storm ($24 billion) and the 11 severe storms at $20.4 billion.

Loss of life also increased

NOAA recognizes that quantifying loss from natural hazards and extreme weather events – or really any kind of disaster – is very challenging, because there are so many factors. Insured losses, as mentioned, are the easiest to track – that includes personal property, contents and vehicles, destruction of infrastructure, business losses and insured agricultural losses. However, uninsured losses must also be calculated. For Hurricane Ida, $29 billion of the total $65 billion cost was uninsured. On top, of course, is the personal loss: the financial impact of injury and death, the emotional toll of loss of property or even just living through the trauma of a disaster.

The National Defenses Resource Council pointed out that the calculations NOAA uses miss a number of people: “Last year, climate and weather disasters harmed Americans from coast to coast and killed 688 people, by NOAA’s estimate. Unfortunately, climate hazards had even more dangerous consequences last year, including illnesses, injuries, and additional deaths. For example, researchers estimate that hundreds of people died in Oregon and Washington in June 2021’s searing heat dome, but because crop damage and repair costs did not exceed $1 billion during that awful episode, this unprecedented event — assessed by climate science experts as ‘virtually impossible’ without the influence of human-caused climate change — is not included in NOAA’s 2021 dollar figure.”

Last year was one of the toughest for the U.S. in more than two decades when measuring loss of life. Nearly 700 Americans died in one of the 20 billion-dollar disasters, which is the sixth-highest U.S. death toll since 1980, but the highest in the contiguous U.S. since 2011. It is more than double 2020’s deaths (262) and almost double the average of 361 deaths. The total includes “229 deaths in droughts in the western U.S. and 226 deaths during the February cold wave.” There were about 10,000 people killed in disasters globally, which is comparable to the past several years.

Lessons for philanthropy

So, what does this mean for us as funders?

Nowhere is safe. Living in the Gulf South, I’m often asked why I choose to live in a hurricane-prone area. Yet, as secondary perils show us, disasters, often quite impactful ones, happen everywhere. The tornado outbreaks in early and mid-December, show how true that is. Don’t think you can put off planning because it hasn’t happened to your community yet.

Natural hazards and severe weather events are increasing, and philanthropy needs to pay attention to that. What steps can we take to mitigate or prevent damage ahead of time? Can we invest in early warning systems and better climate prediction models to help reduce loss of life? The most recent Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report, which includes all types of disasters, shows funders only contributed $359 million in 2019, just a fraction of actual costs of the disasters that year. As the number and cost of disasters increase, funders need to look into supporting mitigation, preparedness and recovery.

All funders must be disaster funders. CDP has often said, “all funders are disaster funders,” but I don’t think all funders consider that to be their role. Disasters are having a direct impact on our communities and the social safety net needs to be strengthened to reduce the harms that they cause.