More Disasters Mean Changes and Challenges for Foundations

The year 2012 was a big year for weather and climate disaster events. Some of these disasters affected millions of people and attracted major media attention. Superstorm Sandy — the second biggest storm in American history — caused more than $70 billion in damage as it raced up the East Coast. Large swaths of the […]

The year 2012 was a big year for weather and climate disaster events.

Some of these disasters affected millions of people and attracted major media attention. Superstorm Sandy — the second biggest storm in American history — caused more than $70 billion in damage as it raced up the East Coast. Large swaths of the New Jersey and New York coastline are only now being rebuilt. Earlier in the year, Hurricane Isaac followed a path eerily similar to the one Katrina took, creating much destruction in Mississippi and Louisiana. A mid-summer derecho roared through the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area, felling thousands of trees and leaving hundreds of thousands of people without power for days, including this writer. What about some of the other events? Unless you lived through them, it’s unlikely you remember them, or are even aware they occurred. But they did, and each one caused more than a billion dollars in damage and resulted in the loss of lives.

What can we learn from the report? How can we learn from the devastation left in the wake of 2012 and become better prepared for the future?

You Live in a Disaster-Prone Area

We used to think about weather disasters as something that happened to “someone else,” because unlike — say, Bangladesh or the Gulf Coast — these kinds of events just don’t happen where we live. That’s no longer true, if it ever was. Disasters are happening more frequently, and with greater intensity, right in our backyard. Rainstorms and snowstorms seem to break historic records with increasing regularity. Hundred-year floods now occur every decade. Regardless of where you live, your community is a candidate for a natural disaster.

Your Foundation Is a Disaster Funder

Many foundations give to catastrophic disaster relief efforts, but relatively few would consider their foundations to be regular funders of such efforts. Likewise, when a disaster hits, funders in affected communities are inclined to support local relief and recovery efforts. A prime example is the Oklahoma City Community Foundation, which acknowledges that tornadoes are a reccurring event in that community and has a tornado fund in place to help local residents recover and rebuild after the next disaster strikes.

For many foundations, however, disaster relief falls outside their normal grantmaking guidelines. But does it? When disaster strikes, the destruction often is multi-dimensional, affecting housing, infrastructure, vulnerable populations, and social services. Given that reality, a growing number of foundations are developing strategies to respond to disasters that fall within their grantmaking guidelines. If you are a funder of children’s issues, for instance, look for ways in which children will benefit from your support, whether it’s funding to rebuild damaged schools, establish temporary child care or afterschool programs, provide recreational areas for kids and families, or assist teachers and parents working to help children process the emotional trauma associated with the disaster. The Annie E. Casey Foundation looks to respond to the needs of children in disaster areas as part of its general work with children. Similarly, the Irene W. and C.B. Pennington Foundation has long been a leader in addressing mental health issues caused by disasters. The same rule of thumb should apply whether your focus is programs for the elderly, the environment, or food security.

Disasters Can No Longer Be Treated as Ad Hoc Events

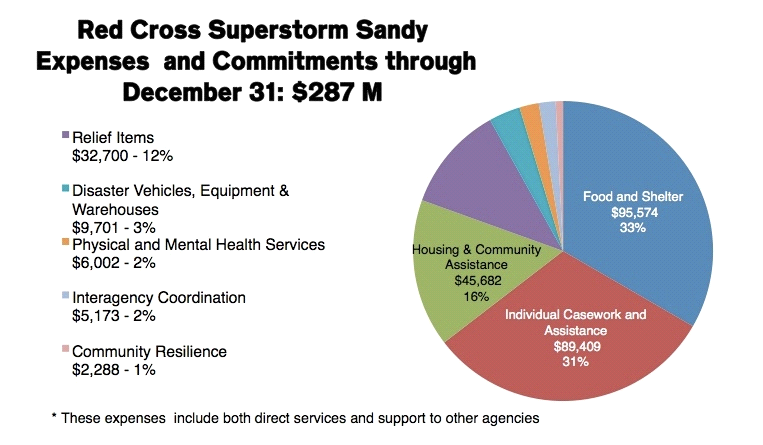

The tendency of most philanthropists is to assume that disasters are one-time events and that life — and grantmaking — can quickly return to normal. But disasters have become the new normal. Ad hoc approaches to disaster response are no longer sufficient. In order to become more effective in our disaster philanthropy, we need to learn from our mistakes, try new approaches, and be more systematic, all the while recognizing that disasters are happening more frequently, thus putting discretionary grant programs under increasing strain. With that in mind, the Center for Disaster Philanthropy works to encourage funders to act collaboratively, thereby maximizing their efficiency and impact. More than twenty funders participated in CDP’s Hurricane Sandy Disaster Fund, enabling a thoughtful, well-researched approach to long-term recovery in the affected region.

Planning, Preparation, and Mitigation

At CDP, we urge all donors to focus not just on immediate relief but to consider the full arc of disasters — from planning, preparation, and mitigation to the long and arduous task of rebuilding. Most disaster funding is still driven by the emotions experienced immediately following a disaster, and most funding still is awarded within two months of an event. The Conrad A. Hilton Foundation, one of the leaders in the field of disaster funding, recommends allocating one-third of a disaster grants budget to planning, another third to relief, and a final third to recovery efforts. The UPS Foundation takes a similar approach. The Patterson Foundation, although relatively new to disaster funding, is focusing most of its funding on long-term recovery and rebuilding efforts, or what it likes to call “”patient capital.””

Of course, funding always is needed to help communities and nonprofit organizations create and implement well-thought-out contingency plans for future disasters. One of the leaders in this area is the Rockefeller Foundation, which has pledged $100 million to help cities become more resilient with respect to the inevitable effects of climate change. In addition, Superstorm Sandy sparked a serious discussion about climate change adaptation efforts and the steps needed to mitigate future storm damage in coastal areas of New York and New Jersey. One such effort, the New Jersey Recovery Fund, which was created by the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation and the Community Foundation of New Jersey, is funding efforts to encourage citizen input on these difficult public policy issues as well as continued media coverage of long-term recovery efforts in the region.

Looking to the Future

As this commentary is being prepared, wildfires are raging in Colorado for the second straight week. In a webinar to be co-hosted by CDP on June 27, Gary Bell of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicts a 70 percent probability of an above-normal hurricane season in the Atlantic basin, with the possibility of thirteen to twenty named storms. Elsewhere, monsoon rains have caused catastrophic flooding in northern India and the hurricane season in the Central Pacific basin is off to a fast start with three cyclone-strength storms already recorded.

Philanthropy needs to be prepared.

More like this