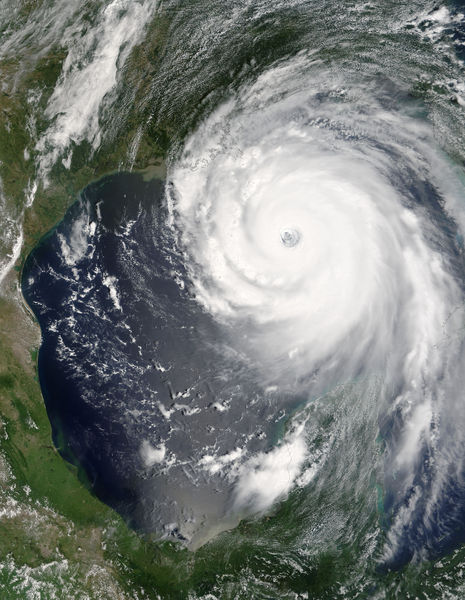

Ten Years Later: CDP Advisory Council Reflects on Katrina

Ten years ago this week, Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast, becoming one of the worst natural disasters in American history. We asked members of the CDP Advisory Council about their memories of Katrina’s landfall, the long recovery process, and the lessons learned a decade ago. Where were you when Hurricane Katrina made […]

Ten years ago this week, Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast, becoming one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

Ten years ago this week, Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast, becoming one of the worst natural disasters in American history.

We asked members of the CDP Advisory Council about their memories of Katrina’s landfall, the long recovery process, and the lessons learned a decade ago.

Where were you when Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast?

William J. Garvelink, senior advisor, U.S. leadership in development, Center for Strategic and International Studies: I was in USAID, as the Senior Deputy Administrator at Bureau for Democracy, Conflict, and Humanitarian Assistance, which oversees disaster assistance from foreign nations. My job when Katrina hit was to work with FEMA to help coordinate foreign offers of assistance.

Sean Reilly, CEO, Lamar Advertising Company: I was in my house in Baton Rouge. We lost power for about 10 days to two weeks. We were housing people from New Orleans who went on to play large roles in the Katrina recovery.

Michael Brown, Chief Executive Officer & Co-Founder, City Year Inc.: When Katrina made landfall, I remember very well, I was with my family on vacation. We were on our way to Montreal, and as we drove through Vermont, we listened to National Public Radio, closely following news of the storm. We were in very frequent touch by cell phone with our dear friends from Baton Rouge, Jennifer Eplett Reilly and Sean Reilly.

Kathleen Loehr, Principal, Kathleen Loehr & Associates: I was at the American Red Cross national headquarters, heading up all Development. We tracked Hurricane Katrina very closely, and I remember at one point thinking “we’ve dodged a bullet” when the hurricane hit landfall at a lower intensity. Of course, once the levees broke, it was a whole new story. What would have been busy hurricane fundraising for the victims of the LA area became national fundraising for a mega-disaster unlike anything we had ever seen.

Billy Shore, Founder and Chief Executive Officer, Share Our Strength: I was on a family vacation in Maine which was overtaken by being glued to the TV and coordinating with the Share Our Strength team as to what our response might be.

Ky Luu, executive director, Disaster Resilience Leadership Academy, Tulane University: I was in Kabul, Afghanistan when Hurricane Katrina made landfall. At the time, I was with the International Medical Corps (IMC) starting up an emergency obstetric training program for doctors and nurses at Rabia Balki hospital. This was a year before my appointment with the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance (USAID/OFDA).

Joseph Booth, Executive Director, Stephenson Disaster Management Institute: I was in the Louisiana State Police Emergency Operation Center managing the State Police response.

Clay Whybark, Senior Academic Advisor to the Institute for Defense and Business: I was at home, here in North Carolina, preparing for a week of involvement with the Institute’s MBA students while in their residency. At the same time, my wife was preparing to leave for several days in Washington State. Of course we followed the event as a family until she left and it was a topic in the sessions with the MBA students.

What role did you play in the recovery efforts?

Garvelink: We worked to meet immediate needs in the humanitarian crisis.

Reilly: I helped found the Louisiana Recovery Authority, set up by Gov. Blanco to direct rebuilding. The LRA was modeled after the Lower Manhattan Recovery Association and was tasked to figure out how to direct rebuilding. It provided legislative and governance structure to rebuild stronger and more resilient.

I also helped found the Family Recovery Corps which organized immediate relief efforts and outreach efforts to displaced Louisiana citizens and coordinated state agencies and local nonprofits for recovery. It eventually became the Louisiana Family Recovery Corps.

Brown: During and after the storm, I was in constant contact with Jennifer Eplett Reilly, who had helped found City Year two decades earlier. We had long talked about the idea of bringing City Year to Baton Rouge and after the storm we just knew that we had to do everything we could, as an organization, to help. Starting a City Year site usually takes two years, under the smoothest of circumstances. But we got to work and were able to launch City Year Louisiana—which later became City Year Baton Rouge and City Year New Orleans—in just 100 days, the quickest launch in our history.

Loehr: My role in the recovery was ensuring that enough funding would come into the ARC to cover the costs. Based on previous hurricanes, and all the fundraising vehicles we knew would be activated, we were positive that $400K could be raised. However the stakes had changed; we had unknown new costs to deliver our services in an entirely new way given the millions affected in multiple locations as they were sent to safety and the inability to “case manage” their support family by family. The new costs were estimated to be close to $1B given the number of shelters across the nation, the unprecedented numbers affected, and the new systems we had to stand up to deliver support. We had daily leadership meetings and the CFO and I always sat side by side – he reporting on expenses going out and further projections and I on fundraising coming in and further projections. It was a nail biting time because of course we needed to be in action, serving those displaced and in need, from the first hour of the first day.

Shore: We made grants and brought civic leaders and philanthropists from around the U.S. to bear witness to what happened in NOLA and what the future needs would be.

Luu: I established a partnership with Tulane University’s School of Public Health and Tropical Medicine and IMC to address emergency preparedness, public health and social justice issues. It was the first time in IMC’s 21-year history that it responded to a domestic disaster. Hurricane Katrina was also the first time in USAID/OFDA’s 40-year history that it responded to a domestic disaster.

Booth: I was the lead for State Police in response to Katrina and Rita and managed the evacuations of evacuees once on the highway system, rebuilt emergency response networks, coordinated law enforcement services in the affected area, reconstructed a police force in New Orleans in the immediate days post storm, and coordinated with various federal and military operations.

Whybark: My primary role was and continues to be oriented toward helping prepare professionals and organizations to better respond to disasters. I also attempt to persuade faculty to increase their research on responsive logistics and community resiliency. For example, I was a member of team of academics that conducted research on major impediments to making responses to disasters more effective and efficient. This research led to a workshop among practitioners from the military, NGOs, government, companies, academics and others. Out of this workshop came connections, knowledge of others’ capabilities, projects to decrease the impediments and concepts that did improve the responses in other disasters. Moreover, I have been involved in both practitioner and academic programs focused on improving responses. We have increased the logistics content and the variety of the attendees in the programs we run in order to help improve the coordination and cooperation in disaster response.

What do you think were the most important lessons learned from Hurricane Katrina?

Garvelink: Even in a developed country, we need well-thought out systems for coordinating relief, both domestically and internationally. We need a better system to receive foreign assistance offers in major disasters. That’s something we’ve never thought seriously about before.

Reilly: Where we had missteps in rebuilding, it typically resulted from an entity that had responsibility for policy and not implementation.

Planning and thinking about the future: make sure you have a very inclusive planning process that includes everyone and doesn’t make conclusions about what a community should look like in the future. Be very sensitive to everyone’s need to go home.

Brown: First and foremost, the biggest lesson learned from Hurricane Katrina, I think, is that while you cannot control the weather and other natural forces, you can work preventively to mitigate a disaster’s effects. You can build infrastructure that protects both people’s physical and social well-being. We have to be very mindful to be sure we are doing this – we should never under-invest in protection and prevention. Second, we need to respond to crises with the urgency and scale required to make the biggest possible difference in the shortest possible time. Third, we need to understand that while buildings and other physical infrastructure can be repaired, social wounds take longer to heal and may, in the end, require more longer-term investment and care.

Loehr: My big lessons from Katrina:

Partnership – we could not have delivered our services if it were not for many on-going partners who stepped up, and new ones who stepped in.

Transparency – it was an incredibly confusing time for all, and the media added to the confusion at times. ARC was transparent about the successes and the tough times, such as when fraud occurred as we were providing financial assistance in new ways. We were also transparent in how the early funds would be used, as well as the long term needs.

Donor education – donors were generous in the first wave of the incredible need, AND I was on the phone constantly educating our current and new donors about the scale of this disaster and the need for funds long term. This is the first time I believe that donors had begun to take in the full cycle of a disaster – from mitigation (why HAD the levees broken) to preparedness (dozens of stories about who was prepared and who was not) to the immediate response to long term recovery.

Focus and Trust – Amid the noise of media pointing fingers, and donors calling, and Congress investigating, our fundraising team stayed focused on bringing in the money to serve the people. I have hundreds of tear-jerking moments in my memory of caring donors hugging families in shelters, of partners providing leaders and employees to augment our capacity to serve, of donor calls when donors simply asked “what more can we do?”

Shore: I’m not even sure where to start. That’s a big question. The need for coordination. The need to understand the distinction between manmade problems and acts of nature. The need for community building across traditional sectors.

Luu: As a result of Hurricane Katrina, the U.S government established policies and procedures to manage the flow of international resources into the United States under the National Response Framework (NRF) and developed the International Assistance System concept of operations. Because the U.S. government had not received substantial amounts of international disaster assistance before, ad hoc procedures were developed to accept, receive and distribute the cash and in-kind assistance. The lack of procedures, inadequate information up front about the donations, and insufficient coordination resulted in the U.S. government agreeing to receive food and medical items that were unsuitable for use in the United States. In the end, the U.S. government had to pay for storage costs, transport of the in-kind goods for use outside of the US, and costs associated with disposal of food and medicines.

Booth: Everyone needs to plan for disasters with consequences far beyond your response capability, prepare the population to be self sustaining for a 72-hour period, and form relationships with a wide variety of public, private, and volunteer organizations that can support you in a disaster.

Whybark: One of the very clear lessons that came out of the experience of Katrina was how much we need to learn about responding to disasters and the long economic reconstruction tail that results. The lesson that has most influenced my work is that of how bad the response to Katrina was. As a result, much of my effort has been devoted to finding ways to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of the response to disasters. Tangentially, I have been interested in improving the funds flow to the recovery and reconstruction phase. As a reminder of the need, the 10th anniversary retrospective on Katrina has shown how much still remains to be done in many part of New Orleans.

How is CDP helping to implement the lessons of Katrina?

Garvelink: CDP plays a unique role in filling a gap to bring funders and providers together to better understand needs on the ground in disaster areas.

Reilly: If people believe that they can give money that’s going to be directed, impactful, and they have confidence in that regard, they’ll give more. CDP has led to that confidence.

I recall talking to other government funders and foundations – if there was a whiff that the folks spending the money couldn’t be trusted, the money wouldn’t come.

Brown: CDP is an essential and critical institution, one that is taking on the biggest lesson of Hurricane Katrina – the importance of prevention and preparation. CDP is working to ensure that we have well thought through plans preparation, including communication and coordination. This is such important work, and CDP’s very existence is a demonstration that we are learning from Katrina and putting that learning into action.

Loehr: CDP is critical to implementing these lessons – in many ways CDP was born from Katrina. We focus on partnerships, either keeping partnered alliances informed or helping broker new partnerships. We certainly are transparent – in our sharing of lessons learned, best practices, and real time information as we gain it. A core strategy is educating donors about the disaster cycle and the importance of funding before or after the immediate response. And finally, the CDP name IS the FOCUS – focus on how the educate donors to maximize the support for disasters that are only growing in scale and scope.

Shore: CDP has helped to codify learnings, be a central repository of knowledge, be a voice.

Luu: A key element of strengthening resilience and reducing disaster risks is learning and knowledge management. There are many lessons that emerge from disaster after action reports year after year. However, many of these “lessons” do not result in improvements in disaster preparedness, response and recovery due to a lack of leadership. CDP needs to continue to assert a leadership role in managing and disseminating knowledge around best practices that results in real actions to strengthen and improve the effectiveness of disaster assistance.

Booth: CDP plays a vital role in facilitating discussion and coordination between various resource providers of vital disaster response and recovery services.

Whybark: The CDP has compiled resources for and directed donors to reconstruction after disasters. The Center is involved in a study of philanthropical funds and their flows. This will provide the basis for increased fact-driven recommendations for funds flows and priorities. Also, by providing information on current disasters and the status of recovery efforts in previous events, CDP helps to focus attention on critical recovery needs long after the media has gone away.

More like this

Vulnerable Populations Needs Special Attention During Disasters