What We Can Learn From the MacArthur Foundation’s Response to Hurricanes Rita and Katrina

It’s a familiar story: disaster strikes, donors immediately spring into action, showering nonprofits with millions of dollars and then move on. Afterwards, you’re likely to hear a common refrain: “we’re not disaster philanthropists – we were just responding to an emergency and we’re eager to get back to normal.” In order for disaster philanthropy to […]

It’s a familiar story: disaster strikes, donors immediately spring into action, showering nonprofits with millions of dollars and then move on. Afterwards, you’re likely to hear a common refrain: “we’re not disaster philanthropists – we were just responding to an emergency and we’re eager to get back to normal.” In order for disaster philanthropy to improve, we need more rigor in analyzing how disaster philanthropy decisions are made and how to make disaster grantmaking more effective.

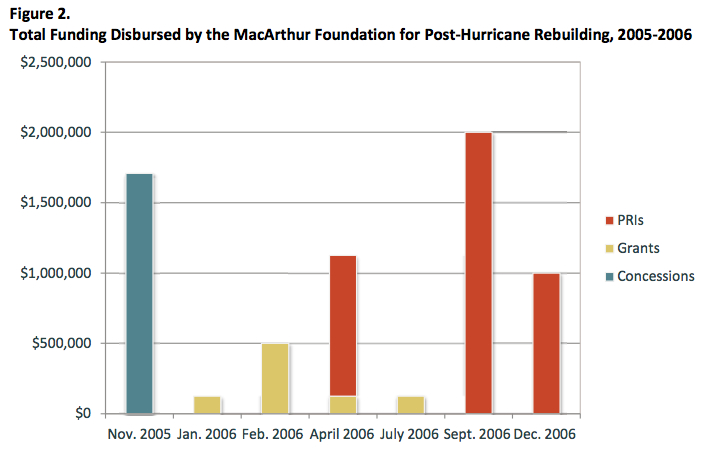

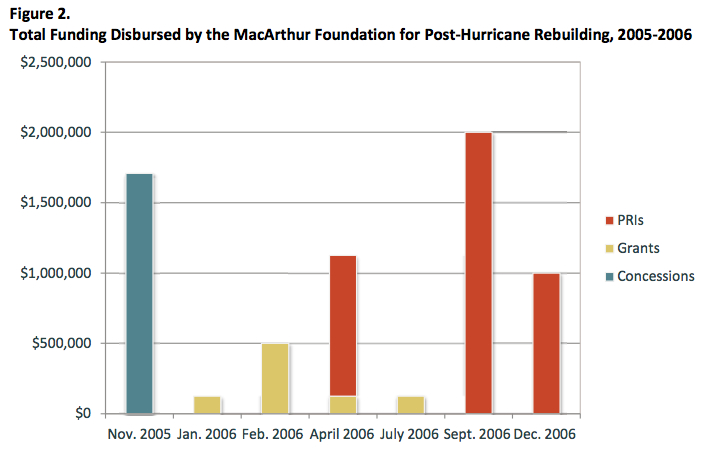

We were pleased therefore to learn that MacArthur Foundation commissioned Arabella Advisors to undertake an analysis of the over $7 million in grants and PRI’s it awarded after Hurricanes Rita and Katrina. The foundation has wisely agreed to make the study public. (Full disclosure: Arabella Advisors was the fiscal sponsor to CDP until September 2012 and still provides some office services and CDP provided some support to this project.)

The MacArthur Foundation is not a disaster philanthropist, under its Disaster Response Policy; it explicitly states that the foundation does not provide disaster relief, with few exceptions. Since it had no internal disaster grantmaking expertise, it was faced with a dilemma familiar to many foundations: What to do? The foundation decided to take a path of action that we recommend here at CDP: concentrate its efforts in a field where it already had a considerable track record and dedicate its support to organizations with which it had a previous relationships — in the fields of affordable housing and community development finance. The report notes “this decision allowed the foundation to expedite the due diligence process, getting needed funds to those responding to the hurricanes more quickly.”

Despite the general success of MacArthur’s efforts, the analysis highlights the difficulties the foundation’s recipients faced in the rebuilding process after these two devastating storms, including “delays in deployment of federal resources; ambiguous regulations; the 2008 housing crisis; the rising costs of insurance, sewage, and water; crime and corruption; and difficulty procuring lots to develop properties.” In other words, disaster philanthropy is hard and complicated work – maybe even more difficult than normal grantmaking. As a result, the authors’ analysis has a number of suggestions including:

- Providing larger and/or multi?year grants to support strategic course corrections.

- Using grants or recoverable grants, rather than more complicated PRIs in some cases.

- Considering supplemental advocacy investments and efforts that aim to streamline regulations.

- Ensuring that foundation staff has the capacity to act as a thought partner with recipients

One area that I wish the study had explored further was MacArthur’s solitary approach. The MacArthur Foundation was unique in its exclusive focus on affordable housing and in its strategy of directly funding organizations, rather than pooling funds with other donors. The report stated, “over half of the top 20 post?hurricane recipients were national or local funding intermediaries that redistributed funds to regional direct service providers.”

Why did MacArthur decide to go it alone? Did this help get more funds out, more quickly? Would collaboration have slowed this work down or could it have increased the impact of its grantmaking?

All in all, it is very thorough study that will help our field better understand what it takes to be a thoughtful and effective donor after a major disaster. We commend the MacArthur Foundation for its disaster grantmaking and for taking the time to study the effectiveness of its work.

Do you have a report on your disaster philanthropy that you’d like to share? If so, please send it to me at bob.ottenhoff@disasterphilanthropy.org.

More like this

Early Research Results Give Insight into Sandy Disaster Giving