Last updated:

2019 Catastrophic River Flooding

Overview

In 2019, there were 14 billion-dollar weather and climate change disasters. Three of them were floods along the Mississippi, Missouri and Arkansas rivers. Approximately 14 million people were impacted by flooding this year, while 200 million were at risk.

At one point in the spring of 2019, the National Oceanic Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) had warned that two-thirds of the lower 48 states could see flooding. The predictions were pretty close, but it was the states in the Midwest that bore – and continue to shoulder – the brunt of the impact. Other states – including Mississippi and Louisiana — flooded as well and the flooding only began to abate in early Nov. 2019.

(Photo: The swollen Pecatonica River spills into downtown Darlington, Wisconsin, on Thursday, March 14, 2019. Source: Dave Kettering/Telegraph Herald via AP)

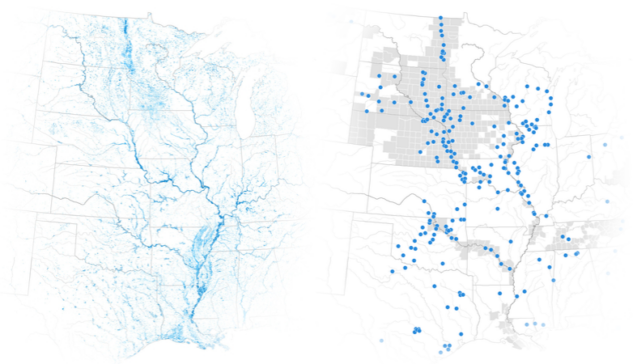

The Mississippi River flooding from spring through July was the longest flood on record, breaking the 1927 Great Flood record. Unlike tornadoes or earthquakes that are geographically local, river flooding is usually a multi-state event. From a tiny stream coming out of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, the Mississippi River travels 2,350 miles south to the Gulf of Mexico. Along the way, hundreds of other tributaries – large and small – including the Ohio and Missouri Rivers feed into the Mississippi. The Mississippi River drainage basin includes water from parts or all of 31 states and two Canadian provinces. In fact, 41 percent of the contiguous U.S. and 15 percent of North America drain into the Mississippi River basin. Along with its distributary, the Atchafalaya River, the Mississippi/Atchafalaya River Basin (MARB), is the third largest in the world (after the Amazon and Congo basins) at 1,245,000 square miles. Once flooding has started in the north, there is little communities farther south can do besides prepare and wait.

Given that the U.S. experienced its wettest winter since 1895, combined with heavy snow in Canada, many rivers – including the Mississippi, Ohio and Missouri – were at high levels before “Biblical rains” hit the area … repeatedly. The bomb cyclone kicked off the first round of flooding, but water levels stayed high and much of the region experienced a second round of flooding between April and August. In September, several states in the Missouri River basin had in excess of 400 percent more rainfall than normal in the first two weeks of September, leading to a third round of flooding.

On Nov. 2019, the U.S. Government Accountability Office released a report titled “SUPERFUND: EPA Should Take Additional Actions to Manage Risks from Climate Change” in which it identified that 60 percent of the most hazardous waste sites in the United States, known as “Superfund” sites are at risk from climate change. Many of these are placed along the basin of the Mississippi River and could be seriously impacted by repeated severe flooding in that basin.

What was the impact on communities?

To truly grasp the significance of the floods, take a look at the New York Times’ interactive The Great Flood of 2019: A Complete Picture of a Slow-Motion Disaster.

There were three major rounds of flooding between March and September. In many cases, communities flooded more than once, with barely any time in between to clean up or prepare for another flood. Spring flooding – March through May – is not unusual given snow melt, rising temperatures and rain. But parts of the Midwest and northern U.S. states were hit with a “bomb cyclone” in March 2019 that dropped immense amounts of snow and rain in a short period of time. Forecaster, Dr. Ryan Maue tweeted at the time, “I have a sense that some have underestimated the power of this #BombCyclone. It’s like [a] 1,000 mile wide hurricane (winds = Cat 1 or 2) was plopped in the middle of the Central Plains but it is snow.”

In Aug. 2019, the USDA Farm Service Agency reported that 19.3 million acres of crops went unplanted that year including 11.2 million acres of corn and 4.35 million acres of soybeans. South Dakota topped the list of states with prevented planting (3.86 million unplanted acres) but five other states – Illinois, Ohio, Missouri, Arkansas and Minnesota – also had over one million acres unplanted. The extreme weather meant that close to 11 percent of the 175 million acres of arable land in that part of the U.S. went unplanted. This agricultural crisis has been compounded by early winter weather and prolonged periods of wet weather that have made it difficult for farmers to harvest crops they did manage to plant. For example, by early June 2019 in Arkansas only half of the soybean crop had been planted; it was nearly finished at that time in 2018. In Nebraska, agriculture – a $20 billion industry – took nearly a $1 billion hit. There were at least $400 million in crop losses and an additional $440 million in cattle losses.

Hundreds of homes were damaged or destroyed across the areas of flooding. Even structures that only have minor flooding will require significant work – according to FEMA, one inch of water in a home equals $25,000 of damage. The river flooding in 2019 is an example of what is to come across the country. A report by the Union of Concerned Scientistshas predicted that in the next 25 years, 300,000 homes and businesses along the coast will face “chronic, disruptive flooding threatening $135 billion in property.”

The Missouri River basin experienced more than a year’s worth of runoff in March-May. Flooding impacts communities throughout the basin from Fairview, Montana/East Fairview, North Dakota to St. Louis, Missouri. The Army Corps of Engineers had to open spillways along the Arkansas River leading to extensive flooding in Oklahoma and Arkansas. Additionally, they opened the Bonnet Carre Spillway on the Mississippi River in Louisiana twice in one year, for the first time ever. Flood gauge records were set at 42 locations between March and July 2019 in six states (South Dakota, Iowa, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Nebraska and Missouri).

Floods are a slow, and sometimes predictable, disaster. This means that communities often know ahead of time they are going to be hit, especially those on major rivers that have flooded farther upstream. However, significant rainfall – especially rain bands setting up over a specific area – can upset even the best laid plans.

Medium and long-term needs in flooded areas include:

- Financial support for restoration of property, business recovery and environmental cleanup.

- Help to fill gaps between insurance payouts and actual costs for those in affected communities. Most homeowner’s insurance does not cover against flooding and flood insurance may not cover all costs incurred. Addressing funding gaps is particularly important in areas that did not get declared by FEMA for individual assistance.

- Funding for remediation of mold in disaster-affected areas.

- Long-term mental health and trauma support.

- Support for farmers who are struggling financially either as a result of the floods or lost crops due to the late harvest.

Preparedness needs in communities include:

- Funding awareness for prevention and mitigation – both at the family/community level and for hard infrastructure. Initiatives might include, for example, homeowners preparing simple kits to have on hand in case of evacuation, outlining evacuation routes and spreading the dangers of driving in flooded waters.

- Support and implement the findings of relevant studies on climate change and on the effects of urbanization on flooding. Mitigating damage in the future will likely take a bigger-picture approach. Flood-mitigation programs are a very expensive proposition and hard for small communities to support, but are often necessary to prevent repetitive flooding, year after year.

CDP's 2019 Midwest Disaster Recovery Fund supported recovery in communities affected by this disaster.

Contact CDP

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working on recovery from this disaster to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

(Photo: Damage from EF3 tornado in El Reno, Oklahoma, May 26, 2019. Source: NWSNorman)

Donor recommendations

If you are a donor looking for recommendations on how to help with disaster recovery, please email Regine A. Webster.

Philanthropic and government support

The Midwest Early Recovery Fund provided more than $1,172,000 to communities affected by flooding this spring. Grantees included 14 organizations in Nebraska, Iowa, Missouri, Oklahoma and South Dakota.

Arkansas: Two Major Disaster Declarations (MDD) were declared for Arkansas (DR-4441 and DR-4460) or severe storms and flooding between May and June. A total of $9 million in Individual Assistance was granted to 925 households and just over $9 million was obligated in public assistance grants.

Illinois: An MDD was declared for Illinois (DR-4461) for severe storms and flooding between Feb. 24 and July 3. Just over $1.4 million was allocated for public assistance grants.

Iowa: An MDD was declared for Iowa (DR-4421) on March 23 for severe storms and flooding. A total of $15.2 million in individual assistance was granted to 1,735 households and $23.2 million was obligated in public assistance grants. A Major Disaster Declaration (DR-4430) was declared for the Sac and Fox Tribe of the Mississippi in Iowa for severe storms and flooding in March and April. To date, $609,262 was obligated in public assistance grants.

Louisiana: An MDD was declared on Sept. 19 for Mississippi River flooding in Louisiana (DR-4462) that occurred between May 10 and July 24. Nearly $759,000 was obligated in public assistance grants.

Minnesota: An MDD was declared for Minnesota (DR-4442) for severe winter storm, straight-line winds and flooding in March and April. Almost $3 million was obligated in public assistance grants.

Mississippi: An MDD was declared for Mississippi (DR-4429) for severe storms, straight-line winds, tornadoes and flooding from February to August. A total of $1.6 million in Individual Assistance was granted to 309 households and $11.3 million was obligated in public assistance grants.

Missouri: Two MDDs were declared for Missouri (DR-4435 and DR-4451) for severe storms, straight-line winds and flooding in March to July. A total of $5.3 million was obligated in public assistance grants. A total of $7.3 million in Individual Assistance was granted to 1,496 households.

Nebraska: An MDD (DR-4420) for severe winter storm, straight-line winds and flooding from March to July. A total of $30 million in Individual Assistance was granted to 3,425 households and $25.9 million was obligated in public assistance grants to the state. On June 17, the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska received a declaration for severe storms and flooding (DR-4446) no additional dollars have been announced for the Ponca Tribe.

North Dakota: Two MDDs – DR-4444 and DR-4475 for flooding in March, April and October. A total of $2.8 million was obligated in public assistance grants.

Oklahoma: An MDD was declared for Oklahoma (DR-4438) for severe storms, straight-line winds, tornadoes and flooding in May and June. A total of $1.6 million in Individual Assistance was granted to 309 households and $11.3 million was obligated in public assistance grants.

South Dakota: Several MDDs (DR-4440, DR-4463, DR-4467, DR-4469) related to flooding and storms in March, April, May, June, July and September. Individual Assistance was granted to a combined total of 2,201 households for of $6.8 million in Individual Assistance and $2.3 million in public assistance. The Ogala-Sioux Tribe (Pine Ridge Indian Reservation) also received a declaration (DR-4448) and $328,000 was obligated in public assistance grants.

Wisconsin: An MDD was declared for Wisconsin (DR-4459) for severe storms, tornadoes, straight-line winds and flooding in July. Only $211,000 was obligated in public assistance grants.

Resources

Floods

Flooding is our nation’s most common natural disaster. Regardless of whether a lake, river or ocean is actually in view, everyone is at some risk of flooding. Flash floods, tropical storms, increased urbanization and the failing of infrastructure such as dams and levees all play a part — and cause millions (sometimes billions) of dollars in damage across the U.S. each year.

Is your community prepared for a disaster?

Explore the Disaster Playbook