Last updated:

Hurricane Irene

Overview

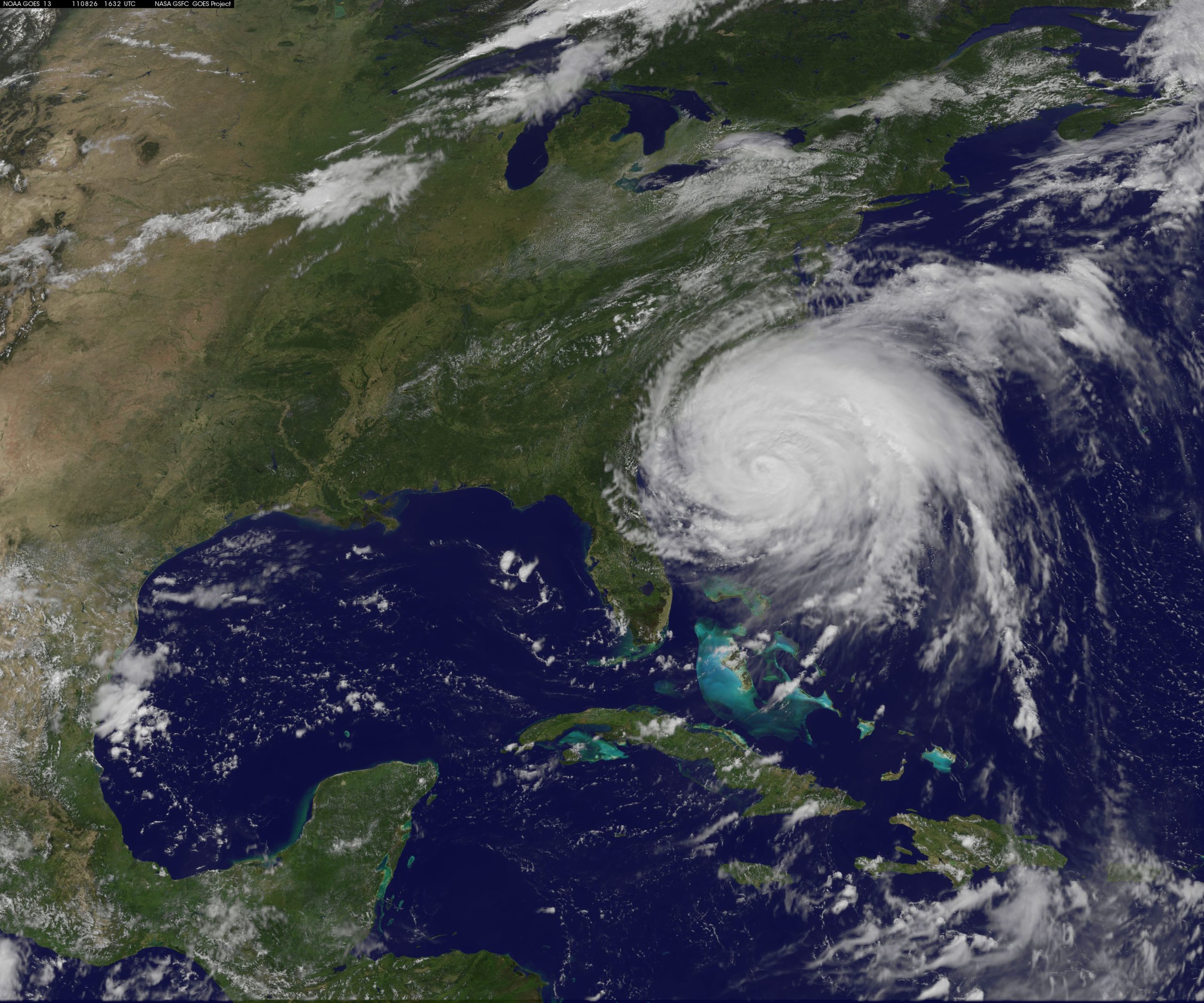

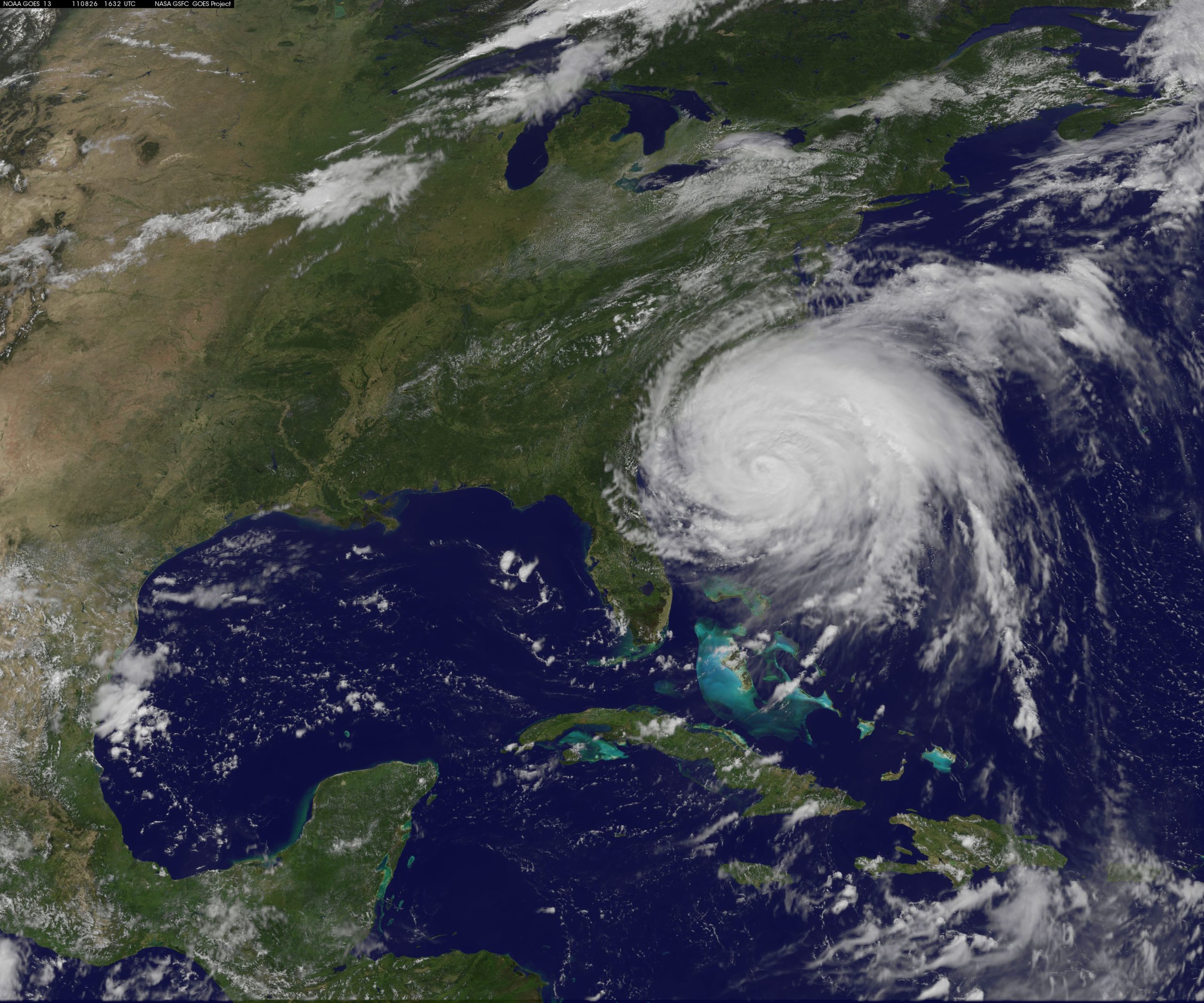

In August 2011, Hurricane Irene barreled towards the eastern seaboard, causing $7 billion in damages. 2.3 million people were urged to evacuate, but many chose to stay home and attempt to weather the 120 mph winds and 20 inches of rain.

In late August 2011, the word quickly spread: Hurricane Irene was headed for the eastern seaboard. From the Carolinas to New England—including Washington D.C. and New York, N.Y.—residents were urged to prepare for the coming storm. Hurricane Irene hit North Carolina’s Outer Banks the morning of Aug. 27, the first hurricane to make landfall in the United States in almost three years. No other hurricane had directly threatened the heavily populated metropolitan New York City area since Hurricane Gloria in 1985.

(Hurricane Irene nears landfall on Aug. 26, 2011. Credit: NASA GSFC GOES Project)

Because of its anticipated trajectory, 2.3 million people were ordered to evacuate—including an unprecedented number in New York. Public service announcements and media reports included urgent pleas, though many chose to stay put instead.

Hurricane Irene was said to cause $7 billion in damage with winds of up to 120 miles per hour and 20 inches of rain. Flooding broke records in 26 rivers, and an estimated 40 people died.

The storm brought damage to crops, boatyards, businesses, and homes, and long-term recovery efforts still are needed. But because it fell short of the most dire predictions, Hurricane Irene has brought questions about the balance of disaster preparedness efforts and “crying wolf”—reinforcing the need for greater accuracy in prediction technology as well as a greater understanding of the benefits of mitigation overall.

Donors wanting to aid in Hurricane Irene recovery as well as mitigate the damage from future storms could:

Provide small loans or award grants for long-term recovery efforts.

Though damage from Hurricane Irene was not as severe as anticipated, many residents of the eastern seaboard remain challenged in their efforts to restore homes, businesses, and livelihoods. Government assistance only goes so far, and the number of U.S.-based disasters in 2011 and 2012 has challenged the federal government to prioritize funds. Private philanthropy is needed to help fill in the gaps.

Support clean-up and research efforts of waters dirtied by sediment and debris from Hurricane Irene and Tropical Storm Lee, which followed not long after.

As of 2012, concern remained that downed branches and trees—especially in Maryland forests—could make the fighting of future wildfires difficult.

Fund mitigation upgrades to homes and businesses and/or insurance workshops to encourage disaster preparedness among the general public.

Awareness of tax credits, benefits, and rewards for preparedness efforts can help overcome apathy. In addition, advocacy could lead to tax credits in more states.

Fund the development of better hurricane tracking systems.

NOAA has a Hurricane Forecast Improvement Program that aims to coordinate research for better predictions of tracking, intensity, and storm surge ability. Investments are needed to enhance observational strategies, improve data assimilation, numerical model systems, and expand forecast applications.

Fund innovative preparedness efforts such as the development of smart grids, automated electric power systems that could minimize power loss for storm-affected communities.

Hurricane Irene brought a surge in support for the smart grid effort, as the storm left an estimated 9 million people without power.

Contact CDP

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working in this crisis to tanya.gulliver-garcia@disasterphilanthropy.org.

Resources

Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

Hurricanes, also called typhoons or cyclones, bring a triple threat: high winds, floods and possible tornadoes. But there’s another “triple” in play: they’re getting stronger, affecting larger stretches of coastline and more Americans are moving into hurricane-prone areas.

Is your community prepared for a disaster?

Explore the Disaster Playbook