Disaster Philanthropy Playbook

Hurricane Florence – CORE

Formerly known as the J/P Haitian Relief Organization, the Community Organized Relief Effort (CORE) brought its international response and recovery experience to domestic disasters in the U.S. Since then, CORE has invested in preparedness and disaster response in hurricane-prone areas in the country with the lens of social justice. They understand that far too often, relief does not reach vulnerable populations and those with the highest needs.

Before Hurricane Florence made landfall on Sept. 14, CORE used available data on socioeconomic characteristics and historical flood maps, combined with ground-truthing through local contacts, to identify the most physically and socioeconomically vulnerable areas along the hurricane’s path. With this data, and an introduction from Native Americans in Philanthropy, CORE started working with the Lumbee tribe of North Carolina immediately after Hurricane Florence hit Robeson County, the state’s most impoverished region.

Addressing Critical Needs With a Long-Term View

Despite being the largest Native American tribe east of the Mississippi River, the Lumbee Tribe has never received federal support. Unlike other federally recognized Native American tribes, the U.S. government does not consider it a “pure” Native American nation because of its mixed ancestry with the Black population. As a result, Lumbee people have suffered a long history of marginalization despite making up 38% of Robeson County’s population.

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) provided CORE’s North Carolina Housing Rehabilitation and Resiliency Program (HRRP) with a $250,000 grant to continue working with the Lumbee Tribe and local municipalities to identify beneficiaries, align its program with the community-driven recovery efforts and build local capacity.

HRRP repaired and retrofitted roofs and implemented mitigation measures such as elevating HVAC units and electrical systems, installing sewage backflow valves and creating wet-proof storage in attics. It also boosted community preparedness by supplying emergency kits and developing and providing customize evacuation protocols and information on asset protection.

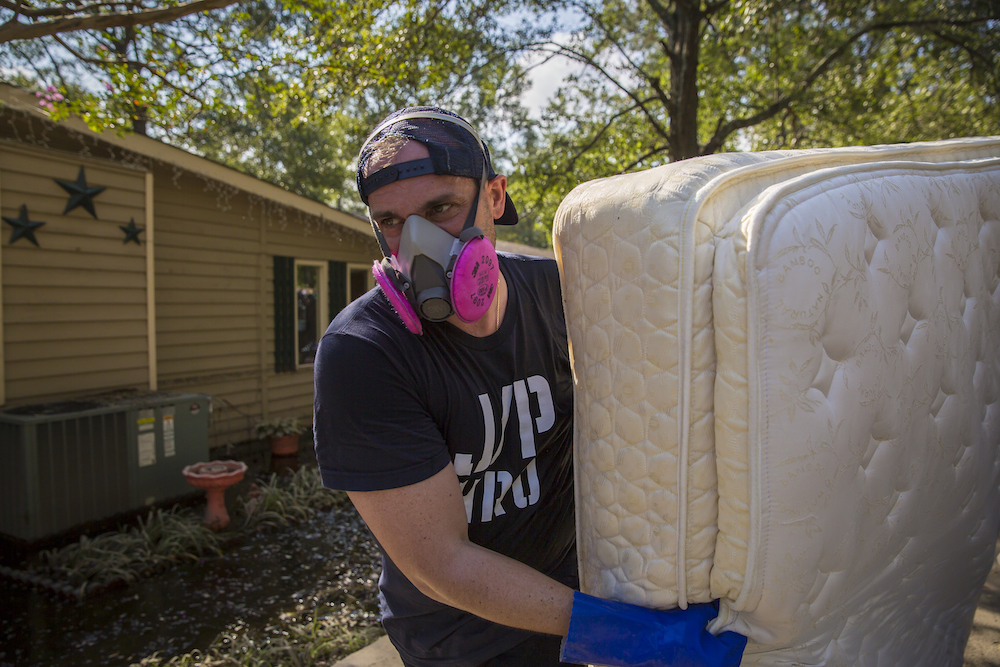

According to Ann Lee, co-founder and CEO of CORE, there is limited funding when CORE first arrives at a community after a disaster. Partnerships and donations from organizations like CDP provide vital funding for a crucial gap period that allows CORE to expand its work on the ground. “You act so fast. It gives us the time and space to get to scale, to get the millions,” Lee said. “That’s also what happened in the Bahamas. Having that flexibility and rapid response mentality fits with us and that timeline. We can do muck outs and quick roof repairs, then pivot to more durable solutions.”

One particularly important factor was CDP’s openness to funding preparedness work, something a lot of funders do not do. “We have always been a huge proponent of preparedness. Where we’re working isn’t rocket science,” said Lee.

Another crucial element is CDP’s support for community-based training. “[These communities] are high-risk neighborhoods, and they don’t get a lot of financial support from FEMA. We always have a social justice angle around preparedness and the actual durable response,” shared Lee. “Philanthropy is often just a humanitarian response or preparedness. But space is opening up, and [CDP] fits in that nexus. It’s easier for us to go into a place, do an assessment and listen to the communities (not putting people into silos).”

An advantage of working CDP Lee added, is that, “It doesn’t ever feel bureaucratic. Working with someone like Brennan [Banks, CDP’s director of recovery funds] who has done this before and knows our language is helpful. You have operational people on your team. On the outside, it feels quick. We can write in shorthand, which streamlined processing things.”

Bringing Communities Together

Two aspects of the work in North Carolina stood out for Lee. CORE had previously developed a youth preparedness program for high-risk Black youth in Savannah, Georgia:

“They came to North Carolina to do muck outs and were forever impacted about what service can do and what it meant,” Lee said. “The families that were there struggling were not from a high socioeconomic status. They had nothing. They lost everything. And yet, they would come every day and feed the kids, bring water and hug them, in tears. Those are the moments – this is why we do the work.”

The second moment came to fruition more recently. CORE’s work in North Carolina served to unite historically segregated and marginalized communities.

“These are racially diverse and unique groups that probably wouldn’t normally trust each other, but they now see the impact of what a muck out and roof repair has done,” Lee said.

“CORE is still in Robeson County, so when the community wanted to begin COVID-19 testing, they knew that CORE was there to fill the gap. CORE provided COVID-19 technical assistance for testing, and now they’re [the county] doing it on their own. Funding helped us really seed and dig into that relationship.”