Disaster Philanthropy Playbook

Social Capital and Disasters

This strategy was developed in partnership with Dr. Gregory R. Witkowski and his students in the ‘Disaster and Community: Philanthropic and Nonprofit Engagement’ graduate course at Columbia University’s School of Professional Studies. The research and writing were carried out by Caroline Schiavo (lead), Cheryl Brandon, Bernard Figueroa and Barbara Selman, with final editing by CDP staff.

Introduction

Why do some communities have the social capital resources to be more resilient than others?

When considering this question, philanthropic donors must consider varying perspectives. To build community resilience, donors must understand the types of social capital, the theories behind them and key terminology.

Community resilience is defined as “the collective activity of a neighborhood or geographically defined areas to deal with stressors and efficiently resume the rhythms of daily life through cooperation following shocks (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015, p. 255).”

Social capital is the collection of resources “linked to networks and access to these resources are secured through group membership (McCarthy, 2013, pp. 3-6).” There is some overlap with financial capital as those with means are more likely to have the time and ability to build social capital, yet social capital is a distinct category built on the depth and breadth of an individual’s relationship. Social capital can be developed without financial capital and therefore can be seen as an inequitable way to achieve individual or collective community outcomes.

There are two main theories of social capital: attitudinal and cognitive aspects and behavioral manifestations.

- Cognitive aspects can be assessed through a level of trust and agreement amongst groups.

- Behavioral manifestations include belonging to society, participation and attendance in meetings, certain social recreation and membership or volunteer-based activities (Aldrich & Meyer, 2015, p. 257).

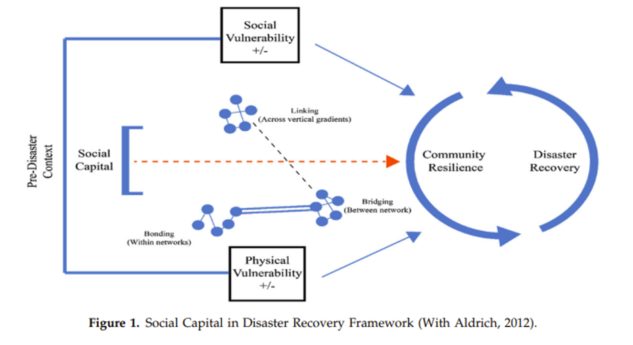

As the figure above describes, there are three types of social capital: bonding, bridging and linking. They work in tandem to create community resilience and aid disaster recovery.

- Bonding involves close relationships among relatives and friends. These kinships are lifesavers, as bonded people are motivated to assist each other when in danger.

- Bridging breaks across different socioeconomic and demographic boundaries. In a disaster, other communities may be more able to provide strategic resources.

- Linking connects everyday people with those in power and authority across formalized levels of work. It is “essential for connection between disaster victims and those who control resources (Kyne & Aldrich, 2019, pp. 3-5).”

Bonding and bridging are horizontal in nature whereas linking is vertical, making it the hardest to use during disaster events.

Innovative Practices

The development of social capital is vital in all phases of a disaster.

- In the preparedness phase, establishing multiple networks before a disaster can assist in a community’s ability to cope and accomplish goals within a condensed period to avoid losses and recover faster (Aldrich, 2012).

- In the relief phase, recovery planning, case management services, volunteer coordination, behavioral health, and psychological and emotional support are important for enhancing social capital.

- In the recovery phase, the provision of technical and financial aid, and housing repair and construction can enhance social capital and help communities return to normal life. Prioritizing marginalized and at-risk populations is also crucial (FEMA, 2011).

During the disaster relief phase, philanthropists instinctively want to provide aid. With communities damaged and local people suffering, the desire to provide relief is compelling. However, disasters function in a cycle, beginning before tragedy strikes and progressing long after the event has ended. Philanthropists, government agencies and foundations often have a vital role during disaster relief, recovery and reconstruction. These donors can provide specialized services and expertise that assist civic leaders and responders during all phases of the disaster cycle, which expands social capital.

Long-term solutions must drive the overall focus on disaster response. Long-term preparedness, reconstruction and recovery efforts can be costly and consist of multilayer resources that can often be overlooked (BOA, 2019). Social capital covers all these domains, creating a cross-section for long-term strategizing. Understanding the needs can help and including affected populations in decisions on how philanthropic resources are used encourages community recovery. Philanthropists have a vital supporting role during disaster prevention and preparedness. Collaborating with affiliates and sharing information with their network are strategic approaches that help communities prepare for a disaster and donors maximize their impact before and after a disaster.

Hosting networking and community-based events like cookouts creates social bonds that provide beneficial opportunities for potential relationship building.

Developing and recording strategy successes and failures helps perfect future planning. Non-governmental organizations and foundations benefit from this information. Philanthropy can develop unity across sectors including opportunities for communication from new and local sources (Rockefeller Philanthropy Advisors, 2022). These efforts contribute toward strategic investments that address chronic social and geographical challenges in the affected areas. Philanthropic investments can improve health and social services, including meeting demands for essentials such as food, water, housing, sanitation facilities and other services for local people (Council of Foundations, 2022).

Ultimately, the efforts are designed to support organizations, partnerships and community leaders who strengthen the global community’s ability to respond to disasters swiftly while providing high-quality resources and outcomes.

What Funders Are Doing

Funders for social capital are active across all disaster phases — preparedness, relief and recovery — as social capital is known for its intertwined relationships. However, this makes it difficult to pinpoint how specific funds for social capital are used.

- Activities such as barbecues, leisure activities in the park, volunteering to clean up urban parks and green spaces, conducting meaningful public activities, organizing a lecture or other group dialogue conversations, or participating in campaigns and public offices can stimulate social capital in tandem with social cohesion (Friedman, 2022). Social capital is linked to improving governance, protecting ecological services, planning coordination and cultivating leadership.

- Social capital can influence the susceptibility to climate change hazards. Before Hurricane Katrina, churches in New Orleans East had developed evacuation plans based on the vulnerability of communities (Behera, 2021).

- Superstorm Sandy made landfall on Oct. 29, 2012, in New Jersey, slamming the coastline with 48 hours of wind, rain, water and record-breaking waves, triggering storm surges and floods. Project Hospitality, a Staten Island, New York-run nonprofit agency for homeless services, raised more than $1.2 million by December 2012 and leveraged its robust network, built on years of existing relationships, to connect service providers and community leaders to identify needs and distribute resources. Critical information was disseminated to the community after the disaster (Williams, 2014). Project Hospitality effectively funded initiatives that used bridging and linking social capital before and after the disaster, to support the work of community organizations and to build resilience.

- Category 4 Hurricane Harvey made landfall in Texas on Aug. 25, 2017. This led to All Hands and Hearts successfully aiding recovery by coordinating and linking community renewal projects that built resilience by boosting morale with the restoration of elements of normalcy and by providing community members with new occupational life skills, equipping them to manage future disasters. All Hands and Hearts volunteers lived and worked alongside the community in Disaster Risk Reduction teams, building resilient schools, homes and infrastructure. They also offered Risk Reduction and Resilience Education to facilitate a culture of safety within schools and communities and engaged residents, leaders and volunteers in community-led projects that rebuilt damaged leisure areas, restoring normalcy (All Hands and Hearts, n.d.).

Key Takeaways

- Social capital is a key element for establishing resilient communities.

- Social capital is important because it strengthens recovery efforts during a disaster among communities through bonding, bridging and linking.

- Collaboration amongst donors, organizations and the communities they serve matters. Through the establishment of social capital, nonprofits and philanthropy can cultivate community connectedness, create safety nets, help people access resources and improve the probability that the community will work through challenges effectively.

- Social capital further spurs collaboration and engagement amongst human and financial capital.

- The development of social capital is vital in all phases of a disaster: preparedness, relief and recovery and reconstruction.

Further Reading

- Alan H. Kwok et al.: Stakeholders’ Perspectives of Social Capital in Informing the Development of Neighborhood-Based Disaster Resilience Measurements

- Beate Völker: Disaster recovery via social capital

- Daniel P. Aldrich Interview with Disaster Zone: The Importance of Social Capital in Disasters

- Joohee Lee et al.: An exploration of posttraumatic growth, loneliness, depression, resilience, and social capital among survivors of Hurricane Katrina and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill