Brother Can You Spare a Dime*: How income affects disaster recovery

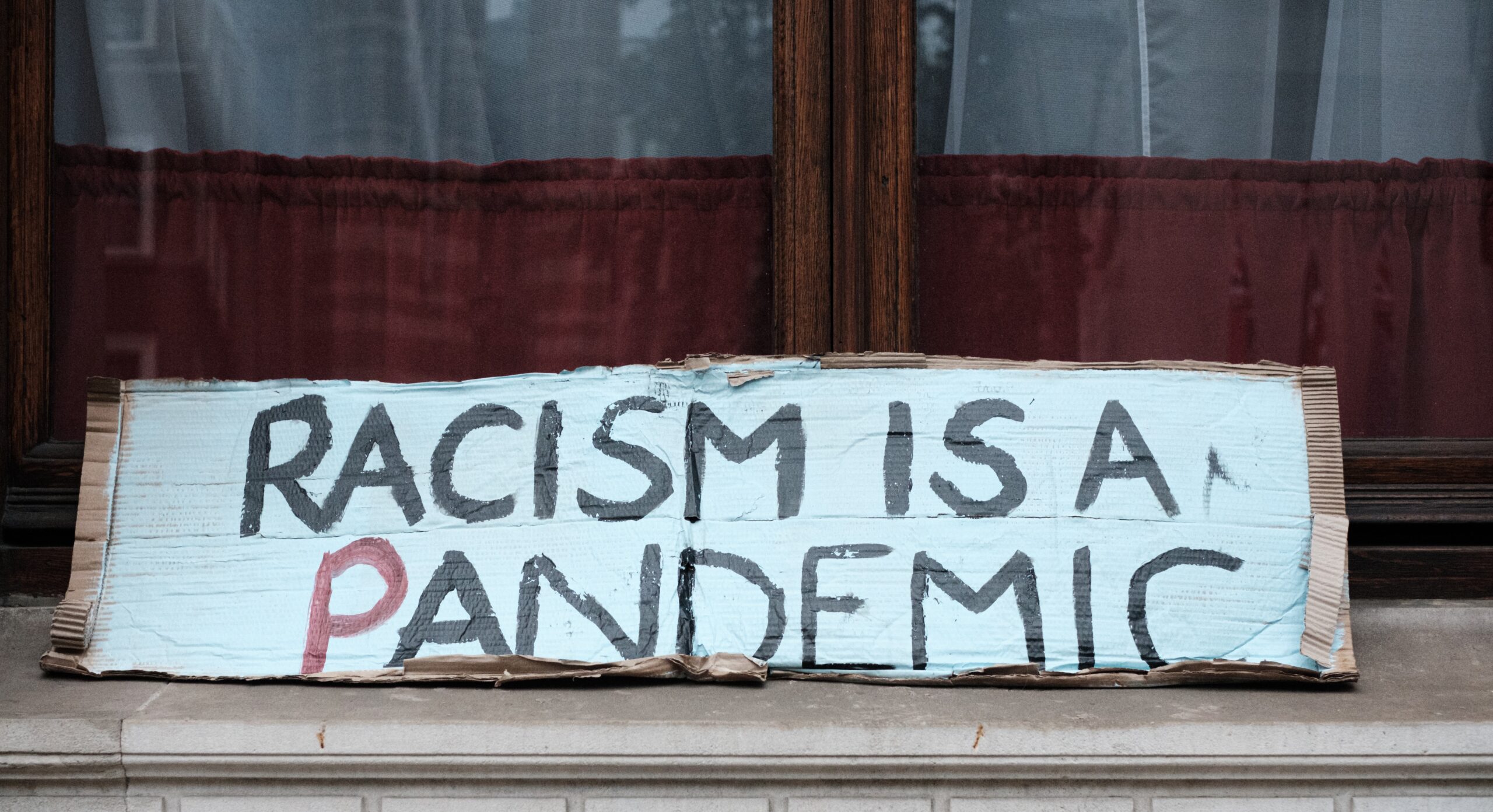

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our “Equity in Disasters” series. The series, which focuses primarily on racial equity and justice issues, also explores how these intersect with other kinds of marginalization and the ways that historical and systemic discrimination create an uneven playing field for recovery. Philanthropy has an important role in alleviating […]

Editor’s Note: This blog is part of our “Equity in Disasters” series. The series, which focuses primarily on racial equity and justice issues, also explores how these intersect with other kinds of marginalization and the ways that historical and systemic discrimination create an uneven playing field for recovery.

Philanthropy has an important role in alleviating poverty, one that it traces to its origins. On History of Giving’s website, John Gardner says, “Wealth is not new. Neither is charity. But the idea of using private wealth imaginatively, constructively, and systematically to attack the fundamental problems of mankind is new.” But the way that philanthropy is being implemented is changing from a charitable model to one based in justice.

COVID-19’s impact on poverty

Research about COVID-19’s impact on poverty is mixed. Prior to the pandemic, about 34 million Americans, 10.5% of the population, lived in poverty. This was down from 2018’s rate of 11.5% and was a significant decrease from 14.8% in 2014. In fact, 2019’s rate was the lowest since 1959 when the census first started tracking poverty data. But COVID-19 changed all that; 2020 saw the largest annual increase since the 1960s. Eight million people fell into poverty in 2020 increasing the rate to 11.8% in December 2020.

However, a New York Times article published at the end of July 2021 highlighted a comprehensive study by the Urban Institute that found the opposite. It said, “The number of poor Americans is expected to fall by nearly 20 million from 2018 levels, a decline of almost 45 percent. The country has never cut poverty so much in such a short period of time, and the development is especially notable since it defies economic headwinds — the economy has nearly seven million fewer jobs than it did before the pandemic.”

The decline in poverty noted in the Urban Institute’s study is linked to the immense investment in social aid programs such as increased food stamps, supplemental unemployment benefits, stimulus checks, a Child Tax Benefit and nutritional programs and food distributions. At a cost of $1 trillion annually, it is unlikely that this spending on social safety nets will continue, and we’ll likely to see a plummet back into poverty when those programs end. The Center for Disease Control announced an eviction moratorium on August 2 that lasts until early October, but only for as long as a community is at high risk for spreading COVID-19. Once that risk decreases, evictions can begin.

The rates of poverty are even more extreme internationally, both before and after the pandemic started. In 2019, 8.2% of the world’s population lived on less than $1.90 a day (the threshold for extreme poverty). While this is an incredible reduction from the 1960s when 80% of the world’s population lived in extreme poverty, the pandemic has set back decades of declining poverty rates. It was already unlikely that the world would achieve its sustainable development goal of eliminating poverty by 2030, despite the great progress to-date. COVID-19 reversed the decline and has added an estimated 124 million more people into extreme poverty.

As discussed in previous blog posts, “intersectionality” – how multiple identities can overlap to create unique opportunities and challenges – causes this rate to increase or decrease within different populations based on various demographic issues. For example, only 2% of full-time working adults in the U.S. live in poverty versus 31% of unemployed adults. About 11% of single dads live in poverty compared to 26% of single moms. While 5% of adults with at least a college degree live in poverty, the rate is almost five times higher (24%) for adults without a high school diploma. Almost one-quarter of adults with a disability live in poverty as do 9% of seniors.

COVID-19 increased poverty while others thrived

The pandemic also had a racially disproportionate impact. More than one-quarter of the growth in poverty in the U.S. – 2.4 million individuals – was among people identifying as Black (nearly 6% of the African American population in the U.S.), resulting in a 5.4% increase in the poverty rate for Black Americans.

Nearly 75 million people lost their jobs or had their work reduced in the first year of the pandemic, with those in lower-paying jobs most affected. (Lower-paying jobs make up 30% of all jobs but represent 54% of lost jobs from Feb. 2020 to May 2021.)

However, not everyone fared badly during the pandemic. In a March 2021 report, Human Rights Watch said, “Higher-income people have been relatively unscathed economically. Despite the worst economic contraction since the Great Depression, the collective wealth of the US’ 651 billionaires has jumped by over $1 trillion since the beginning of the pandemic, a 36 percent leap.”

Poverty and Disasters

Poverty affects people during all phases of disasters, from preparedness and mitigation to relief and recovery. Philanthropy has an important role in addressing poverty before, during and after disasters. At CDP we are talking more about addressing root cause issues, rather than just putting band-aids on the problems they create.

One’s income level affects one’s ability to prepare for a disaster, to evacuate, to return home and to rebuild. In most “at-will” states – where employers have the right to terminate employment at any time — the poverty level is higher if there are no exceptions to the process. While that affects one’s ability to save the necessary resources for evacuation and prepare for a disaster, the potential loss of work and pay is often deemed even more important by workers.

Hourly (non-exempt) employees do not have to be paid for any hours of work missed due to an evacuation or a disaster. Exempt (salaried) employees do have to be paid although employers can require the use of personal days or vacation time for days missed. Furthermore, an exempt employee who chooses to stay home during a disaster because of access or transportation issues can have pay deducted, be required to make up work or have earned paid time off docked. In at-will states, this could also lead to termination meaning some workers will ignore evacuation orders due to fear of losing their job. Migrant workers, who may not have access to information in their native language and/or legal immigration status, are often forced to continue to work in dangerous conditions.

UNICEF says, “Children who grow up impoverished often lack the food, sanitation, shelter, health care and education they need to survive and thrive. Across the world, about 1 billion children are multidimensionally poor, meaning they lack necessities as basic as nutrition or clean water. Some 150 million additional children have been plunged into multidimensional poverty due to COVID-19.” Post-disaster these risks increase dramatically leading to starvation, disease and death.

How philanthropy is supporting those affected by COVID-19

CDP’s COVID-19 Response Fund grants supported a number of initiatives to address economic impacts including:

- Atlanta Wealth Building Initiative was awarded $145,000 for the immediate support of businesses owned by people of color to address the economic disruption caused by COVID-19, as well as support the long-term recovery and sustainability of the small business ecosystem.

- Communities Unlimited was awarded $100,000 to expand and deepen the organization’s capacity to respond to small, rural-based businesses affected by the current COVID-19 pandemic.

- Food Chain Workers Alliance received $150,000 to support the COVID-19 response projects and direct relief funds of members representing food chain workers.

- GiveDirectly was awarded $250,000 to provide $1,000 digital cash transfers to low-income families enrolled in the federal government’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program across the country.

- GOAL, in Northern Iraq, received $250,000 to address multiple needs and build the resilience of the most vulnerable households. As part of this program targeting the most vulnerable disaster-affected communities, GOAL provided a cash transfer to 180 of the most vulnerable refugee and host community households so that families could purchase needed goods and services on the local market. In addition, Financial Literacy and Social Cohesion Training was provided.

Equity requires philanthropy to move beyond charitable giving that provides food, clothing and sustenance to justice work that addresses the root causes of racism, poverty and systemic oppression. Funders can advocate for higher wages and better working conditions, fund labor rights organizations, address the school-to-prison and -military pipelines (especially for people of color), support cash grants and work to seed justice work, organizing and capacity-building opportunities in all of their grants.

[*] Brother Can You Spare a Dime, recorded by Bing Crosby, Written by lyricist Yip Harburg and composer Jay Gorney. – this is one of the “anthems” of the Great Depression. Its message of the everyday person being affected by the Great Depression is relevant to today’s economic situation in light of COVID-19.

More like this

Housing and insurance gaps hinder disaster recovery