Creating a Personal Strategy for Disaster Giving

This interview originally appeared in the T. Rowe Price publication, “Giving Back.” Natural disasters can pose a dilemma for donors. The desire to give immediately to alleviate suffering means they may not always take time to find the best available non-profits to deal with that particular disaster. In this interview, Robert G. Ottenhoff, President and […]

This interview originally appeared in the T. Rowe Price publication, “Giving Back.”

Natural disasters can pose a dilemma for donors. The desire to give immediately to alleviate suffering means they may not always take time to find the best available non-profits to deal with that particular disaster.

In this interview, Robert G. Ottenhoff, President and CEO of the Center for Disaster Philanthropy, offers practical guidelines to help ensure donations go where they’re needed to achieve the maximum benefit. Mr. Ottenhoff has more than 25 years of management experience in public broadcasting and high-tech companies, including nine years as CEO of the Public Broadcasting Service.

What inspired you to join the Center for Disaster Philanthropy as opposed to other charitable organizations?

I spent ten years building GuideStar, providing information to encourage more effective giving. I noticed that most donors knew very little about the proper strategy for dealing with disasters. That’s not surprising because people generally have a group of non-profits they support regularly, but disasters tend to be episodic and unplanned.

When the founders of the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) approached me, I was interested because the hundreds of millions of dollars given each year to disasters aren’t always well spent or coordinated. There’s a sense of urgency when a disaster occurs, and that doesn’t always lead to effective giving.

For American donors, is there a trend toward contributing more or less to international causes?

Over the last decade donors have tended to give more to internationally-focused causes—of certain kinds. The tsunami in Japan and earthquakes in Nepal really attracted people’s attention. Environmental and health issues such as Ebola also played a part, although less so.

In the short term, however, the most recent presidential election may cause donors to re-order their priorities. We’re seeing proposed cuts in government support for domestic and international programs which may cause people to consider whether they should give more to those areas.

“Disasters are becoming so frequent that our old ways of responding to them are not appropriate anymore. We have to think strategically and develop a game plan to get better.”

What is the biggest mistake donors make when they give for disaster relief?

Our research shows that about 80% of all disaster giving happens within a very short period to support immediate relief. Virtually all disaster-related giving stops within about three months, while long-term recovery efforts can take many months or even years. It’s not until later that you see the full impact of a disaster in terms of mental health, housing, and the economy.

We want people to think about the full life cycle of disasters—making contributions to planning and preparation, and mitigation activities. That helps build more resilient communities that can bounce back faster after a disaster.

You talk about donors needing to create strategies in line with their priorities and values. How is this possible since many people often make donations for disasters based on emotional criteria?

Donors can become more strategic, starting with defining their values and priorities. Before disaster strikes, they should identify what they are interested in (children, the environment), and find organizations that do good disaster-related work in these areas. See which organizations excel at different stages of a disaster and who has expertise and facilities in the affected area. Then donors have the information they need when a disaster occurs.

What is the best way for donors to address the long-term needs of communities after catastrophic disasters?

Donors should realize non-profits will need their dollars as much or even more one to three months out compared to immediately after the disaster. They should check an organization’s website for a needs summary, which shows what they’ll be working on over the next few months and how they can use donor support.

What types of guidance do your clients request most often?

Most requests come after disasters—we wish more people would contact us before. Typically donors see something on television and are unsure where to direct their donations. People want to know if organizations are legitimate and who does the best work in a given area.

What are low-attention disasters and what challenges do they present?

There’s a direct correlation between media coverage of disasters and giving. For example, tornadoes and hurricanes are very high profile. In contrast, floods in the mid-west and Louisiana (where 200,000 households were affected) often get only one day’s coverage.

People are surprised when I say there were 15 disasters in the United States in 2016 that caused $1 billion or more in damage. They remember hurricanes, not so much floods or wildfires.

Internationally, there are 60 million displaced people in the world—a large number because of natural disasters. This receives relatively little media attention compared to the scale of the suffering.

How can pooling donations through CDP help donors be more efficient?

We do research, consult with subject matter experts, and may even visit affected countries. When donors work with us, they can commit to giving right away and be assured their money will be well spent to achieve the maximum effect.

All donations are well managed by CDP experts—we’re like a mutual fund for disaster giving.

Many people probably don’t think in terms of mitigating the effects of disasters before they happen. Why is this important and how can donors contribute to projects in this area?

As sea levels rise and there’s more flooding we need to emphasize mitigation. For example, groups are doing coastal restoration in Louisiana—rebuilding river banks and forests and planting marsh grass

As the number of disasters grows in frequency and intensity, we need to be better prepared.

More like this

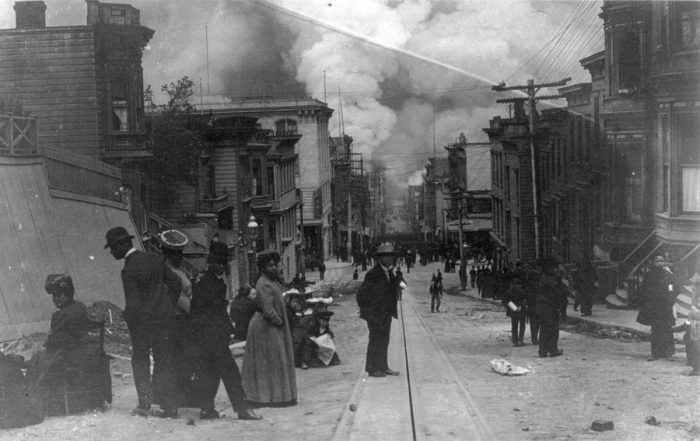

How Black History Has Influenced Disaster Planning