The Rise of the Billion-Dollar Disaster

Disasters are increasing in frequency, and so, too, are their financial impacts. Although the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) tracks philanthropic giving through its report, “Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy: Data to Drive Decisions,” we do not track total disaster cost. And yet, it is significant! Within the U.S., there were “273 weather and […]

Disasters are increasing in frequency, and so, too, are their financial impacts. Although the Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) tracks philanthropic giving through its report, “Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy: Data to Drive Decisions,” we do not track total disaster cost. And yet, it is significant!

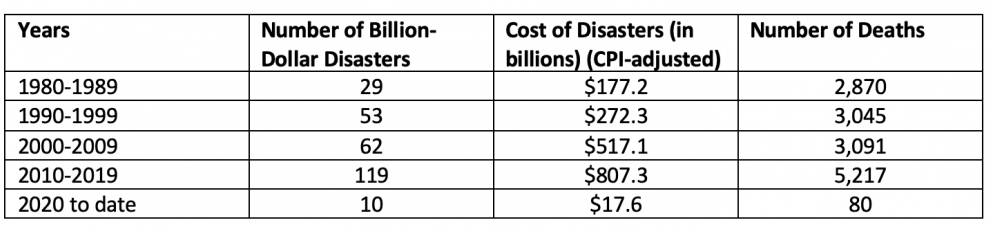

Within the U.S., there were “273 weather and climate disasters since 1980 where overall damages/costs reached or exceeded $1 billion (including consumer price index adjustment to 2020 levels). The total cost of these 273 events exceeds $1.790 trillion” and there were 14,223 lives lost.

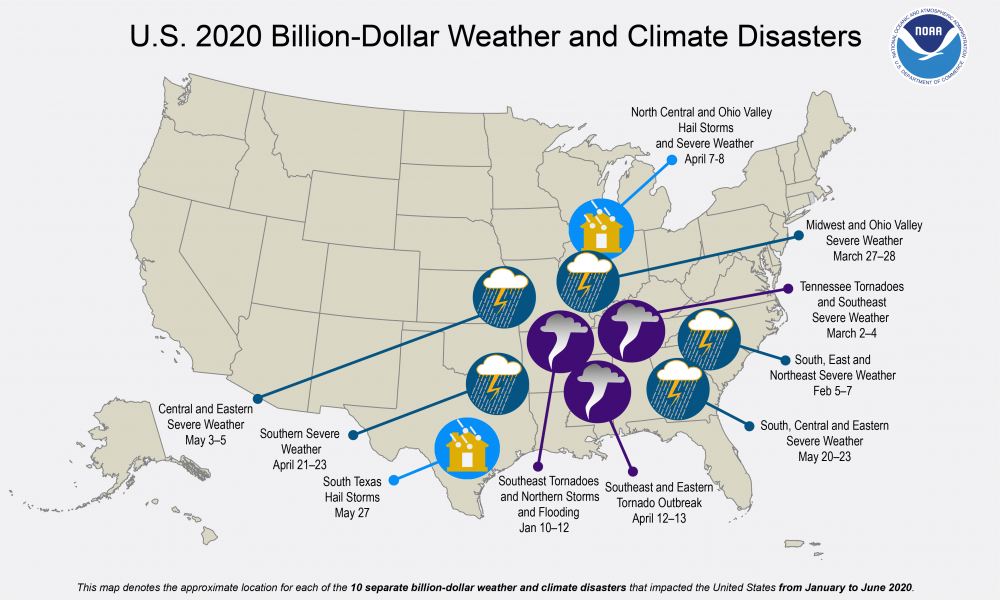

From January to June 2020, 10 storms already have losses exceeding $1 billion. In addition to financial losses, there have also been 80 deaths. None of these disasters were “named events,” such as a hurricane. Since June, other weather-related disasters have occurred. Hurricane Laura is estimated to have caused $8-12 billion in damages, while Hurricane Isaias’s estimate is almost $5 billion.

So what does the data tell us?

2020 marks the sixth consecutive year with at least 10 billion-dollar weather and climate disaster events. Besides these six years, there were only four other years in the last 41 (1980 to 2020) with 10 or more billion-dollar disasters (1998, 2008, 2011 and 2012).

The chart below shows how the number of disasters, the cost and the death toll have increased over the past 41 years.

All kinds of disasters can be billion-dollar disasters. It is not limited to a Category 5 hurricane hitting the coast or a massive wildfire burning through Colorado. Instead, just as in 2020, the largest number of billion-dollar disasters come from everyday storms: a flood after heavy rain, a tornado outbreak or a heavy snowfall. These losses come in the form of destruction of buildings – including homes and businesses – as well as agriculture/crop losses and infrastructure i.e. bridges, dams.

Philanthropy needs to prepare to respond to these storms, especially at a community level. But because they do not attract as much media attention, it is much harder to raise money from outside the affected community. Weather services spend days tracking a hurricane as it heads toward Florida, but the Great Flood of 2016 in Louisiana came from a rain band that unexpectedly stalled over the state.

Lesson one, therefore, is to prepare for the unknown. You may not know what disaster will hit your community. But as COVID-19 has made abundantly clear, we will all be hit by a disaster sooner or later. Instead of focusing on developing hurricane preparedness, evaluate the potential for all kinds of hazards. Think about bringing a generalized perspective to your disaster planning to account for those events you cannot anticipate.

Gather funds in advance. Rather than trying to raise money after the disaster, establish a permanent disaster fund. Such a fund allows funders to negotiate agreements in advance with disaster responding organizations and ensures that money can flow into the community quickly.

Develop your recovery and response plan. Every disaster is different, but the general needs of a community afterward are very similar – food, shelter, mental health support, rebuilding and more. By knowing what you want to fund (CDP generally funds recovery, six to 12 months after the disaster) and how you want to fund it, you can develop the process, protocols and forms, long before you need them.

Before a disaster strikes is also a great time to build relationships with the community. Think outside the box and connect with organizations that are likely to be on the frontlines but are not disaster responders such as food banks, homeless shelters, child care centers and youth programs.

Determine the risks and vulnerabilities of your community. If your area has a retirement community, connect with organizations serving seniors. If your community has many migrant farmworkers, determine what languages your materials will be needed in and connect with immigrant-serving organizations. Those people who are the most vulnerable before a disaster are also the most vulnerable after a disaster strikes.

Philanthropy cannot solve all the problems of disasters, nor can it cover all related costs. But we can plan ahead and be prepared when it happens to our community. Because it will, sooner or later.

More like this

What We Can Learn from Five Years of Mapping Disaster-Related Giving