Hunger

Due to growing inequality, climate disasters and the spread of violent conflict, hunger is rising throughout the world. According to UNOCHA, “Hunger and malnutrition are spreading faster than our ability to respond, yet globally, a third of all food produced is lost or wasted.”

What is hunger?

Hunger is often used interchangeably with the term “food insecure” and describes a regular lack of access to food, which interferes with living a healthy life.

To understand food insecurity, let’s look at the four dimensions of food security:

- Physical availability of food

- Economic and physical access to food

- Food utilization by the body

- Stability of the other three dimensions over time

Food shortages are often caused by crises like disasters or war. In contrast, food insecurity can persist in the short and long term, depending on economic conditions, infrastructure and social policies.

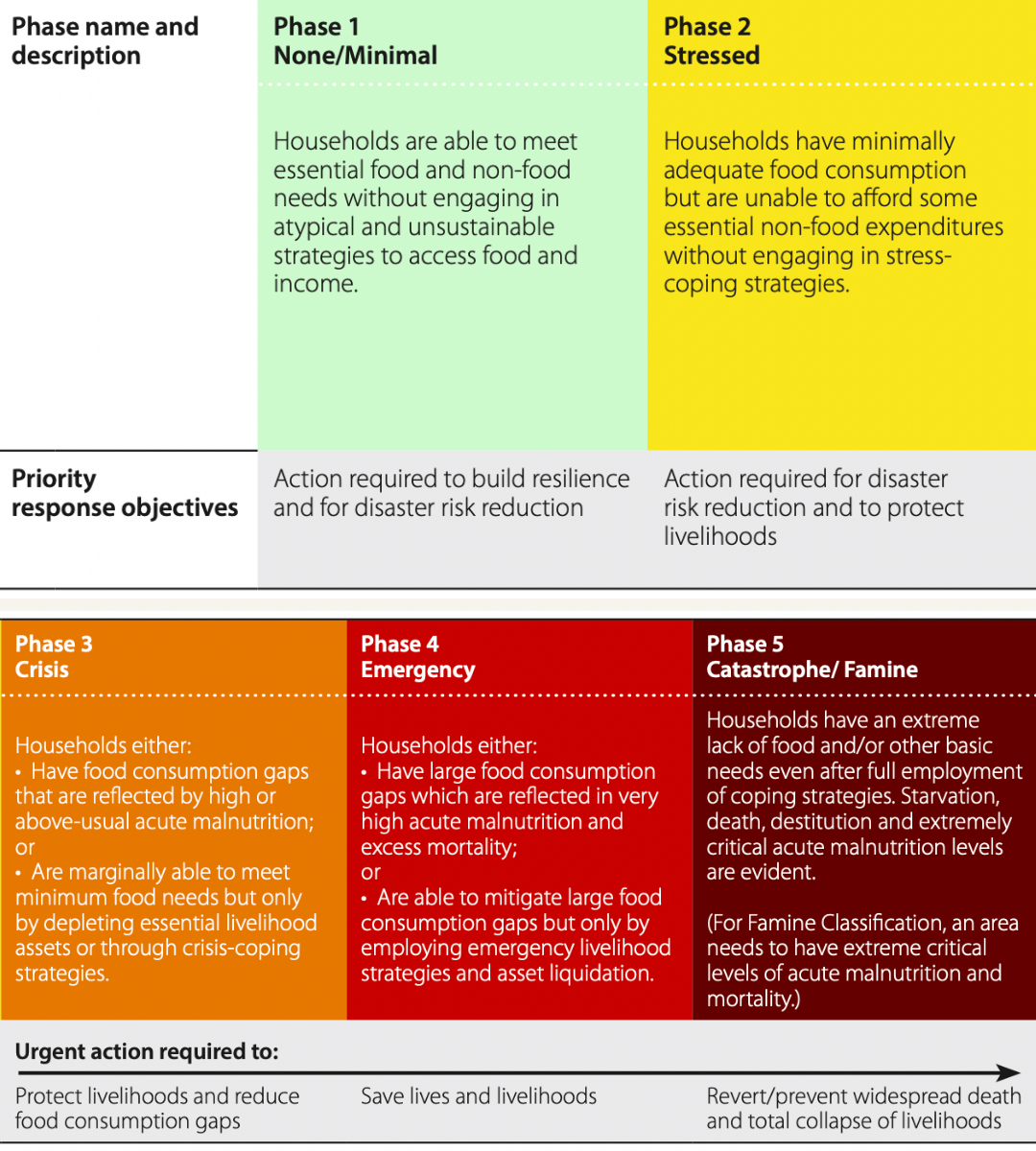

According to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), there are five phases of food insecurity, with Phase 1 indicating no or minimal insecurity and Phase 5 indicating catastrophic food insecurity and/or famine. IPC defines Famine (IPC Phase 5) as: “…A situation in which at least one in five households has an extreme lack of food and faces starvation and destitution, resulting in extremely critical levels of acute malnutrition and death.”

Famine is generally declared by the UN based on multistakeholder consensus in conjunction with the affected country’s government. Thus, it is political in nature. However, people can live in famine-like conditions long before a declaration of famine is made. Therefore, it is critical to act early to save lives.

Who is affected by hunger and how?

- More than 343 million* people faced acute hunger in 2024, the sixth consecutive annual increase.

- Globally, the groups most affected by hunger are women, children, people with disabilities, displaced people and small-scale farmers.

- In the United States, 85%** of people who applied for food assistance in 2023 were female.

The people affected by hunger globally often lack access to resources like land, credit and education, which causes or exacerbates food insecurity. Additionally, they are the groups most likely to be displaced by conflict or a loss of livelihood.

The people most often affected in the U.S. are victims of domestic violence, single mothers, children, low-income households, minority and rural communities, people with disabilities and college students.

Food insecurity can result in malnutrition, a condition that occurs when a person’s diet lacks the nutrients needed for healthy growth and function. Not eating enough food (undernutrition) or consuming too much of the wrong kinds of food (overnutrition) can cause malnutrition. Common signs include weight loss, fatigue, stunted growth in children, and weakened immunity. Conversely, malnutrition caused by overnutrition can result in obesity, heart disease and diabetes. Malnutrition can affect people of all ages but is especially dangerous for young children, pregnant women and older adults. Addressing malnutrition requires access to nutritious food, education about proper nutrition and medical support.

Where does hunger occur?

- 1 in 5 children in the United States suffer from hunger.*

- 52 million people face food insecurity due to conflict, extreme weather and economic instability in West and Central Africa.**

- 95% of people living in IPC Phase 5 (famine or famine-like conditions) live in Sudan and Palestine (Gaza). The remaining 5% live in South Sudan, Mali and Haiti.***

Why does hunger occur?

- Hunger occurs in the United States* because of systemic gaps that prevent resources from reaching the people who need them the most.

- Globally, conflict is the most significant driver of food insecurity.**

- Famine results from a long, slow decline in access to food.

According to Vince Davis, senior director of disaster services for Feeding America, hunger occurs in the United States not because of a lack of money or food but because of systemic gaps that prevent resources from reaching the people who need them the most. Generations of structural inequity, racism, underinvestment and economic dislocation, housing instability, high health care costs and low-wage work are some reasons why people go hungry in the world’s richest country.

Globally, about 282 million people are in IPC Phase 3 or above. Armed conflicts displace communities, destroy infrastructure, and disrupt food production and distribution. Approximately 65% of the world’s hungry live in conflict-affected areas. Additionally, inadequate infrastructure and weak governance hinder food distribution and access.

In the U.S. and abroad, extreme weather events like drought, floods, hurricanes, fire and other disasters can disrupt agricultural growing seasons. This can result in lower food production for local and global consumers. Lower crop yields can also make the lean seasons leaner, contributing to hunger.

Conflict, political, social and economic policies, chronic under-development, weak governance, or a lack of resources all create an environment favorable to famine. An event like a climate disaster may tip a region into famine because it compounds existing vulnerabilities.

How can funders help in the U.S.?

In the United States, hunger can be addressed by:

- Supporting community programs.

- Investing in food access and equity initiatives.

- Supporting farmers and agriculture.

- Advocating for policy changes to expand the social safety net.

To help change policy that affects food insecure people, funders can support diverse coalitions of advocates, banks, health insurance companies and other groups that can collectively make a case to lawmakers about the societal benefits of fighting hunger. It’s also crucial to support resilient agricultural infrastructure so farmers can withstand climate shocks.

Funders can reduce hunger by investing in development and addressing systemic inequalities.

How can funders help abroad?

Globally, funders can reduce hunger by:

- Investing in emergency feeding programs.

- Investing in development to break the cycle of conflict and hunger.

- Investing in anticipatory action programs.

- Supporting sustainability and resilience to climate change.

- Supporting the education and livelihoods of women and girls.

- Funding programs that connect rural farmers to markets.

Because conflict is the top driver of food insecurity, reducing conflict by investing in development is foundational. However, due to recent funding cuts to organizations like the World Food Program, emergency feeding programs have been slashed, putting millions of vulnerable people at risk of starvation. Supporting solutions to this urgent issue is crucial.

Learn more

Additional resources

- CDP disaster profile: Sudan Humanitarian Crisis

- CDP blog post: CDP launches a Sudan Humanitarian Crisis Fund

- CDP webinar: Hunger in the U.S. – How disasters disrupt access to food

- IPC – Famine Facts

- World Food Programme

- International Food Policy Research Institute

- 2025 Global Report on Food Crises

- Tufts University – Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy: Feinstein International Center

- World Hunger Education Service

Sources

Who is affected by hunger and how?

Where does hunger occur?

- *Feeding America

- **2025 Global Report on Food Crises

- ***Reuters: Conflict, extreme weather worsening hunger in West and Central Africa

Why does hunger occur?