Nearly 13 years after gaining independence, people in South Sudan continue to face deteriorating humanitarian conditions.

Conflict, public health challenges, climatic and economic shocks, and poor governance have severely affected people’s livelihoods and hindered access to essential services. Poverty is ubiquitous, exacerbated by these factors. The most recent household survey was conducted in 2016-2017 and revealed that 67.3% of South Sudan’s population lived below the international poverty line.

The Human Development Index, a summary measure of average achievement in key dimensions of human development, ranks South Sudan last globally. South Sudan’s life expectancy is 55, people spend just 5.5 years in school on average and earn $768 a year.

According to the Humanitarian Needs and Response Plan (HNRP) 2024, 9 million people will be in need of humanitarian assistance, with 7.1 million South Sudanese requiring food assistance according to the Integrated Phase Classification (IPC) projection.

In a joint statement issued from Juba on Dec. 11, 2023, Reena Ghelani, United Nations (UN) Famine Prevention and Response Coordinator, and Marie Helene Verney, Acting Humanitarian Coordinator for UNOCHA said, “The people of South Sudan are facing the cumulative and compounding effects of multiple inter-connected crises: insecurity and conflict – including the spillover effects of the crisis in Sudan, climate shocks such as flooding and localized drought-like conditions, and an economic crisis driven by currency depreciation and rising commodities prices.”

Meanwhile, “In 2023, UN and partners received only 55% of the funding required to support those most in need, against about 75% in the previous years. […] As needs continue to outpace resources and with a deficit in coverage and development of basic social services, it’s critical that the Government of South Sudan commit to improving social systems and infrastructure that supports communities to find their way out of food insecurity.”

(Photo: A view of the Protection of Civilians site in Bentiu, South Sudan. Source: World Humanitarian Summit; CC BY-ND 2.0)

Fighting erupted in neighboring Sudan in mid-April 2023 between the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces. The conflict has displaced thousands within Sudan and forced thousands more to flee to South Sudan. Sudan’s conflict is significantly exacerbating the humanitarian situation in South Sudan.

As early as June 2023, Nicholas Haysom, the UN envoy for South Sudan, told the UN Security Council in June 2023 that the capacity of the government and humanitarian organizations to absorb the people crossing the border form Sudan into South Sudan “is under strain,” with limited local resources in border towns, especially Renk. For more, see our Sudan Humanitarian Crisis disaster profile.

Safety and security concerns remain significant and impede humanitarian access.

In a report released in April 2023 by the UN Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan shows “how perpetrators of the most serious crimes – including widespread attacks against civilians and extrajudicial killings – go unpunished, with senior Government officials and military implicated in serious violations.”

On April 3, 2023, the UN Human Rights Council extended the mandate of the Commission on Human Rights in South Sudan. Amnesty International called the extension of the mandate, “an important signal from the Human Rights Council that accountability is key.”

South Sudan is the second most at-risk country to the impacts of a changing climate, including droughts and flooding. The World Bank says 86 million Africans may be made homeless by climate change in the coming decades. The displaced people around the Sudd, a wetland at the center of South Sudan that is twice the size of Belgium, are among the first. UN agencies say four years of record rains have flooded two-thirds of South Sudan. While rainfall during the 2023 rainy season was below average, the World Food Programme (WFP) is expecting flooding during the 2024 rainy season due to El Niño.

Latest Updates

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, March 18

Key facts

- Approximately 67% of South Sudan’s population lives at the international poverty line and the World Bank says, “GDP per-capita growth suggest that extreme poverty will likely continue to increase, reaching 73% of the population by 2024.” The inflation rate for consumer prices in South Sudan moved over the past 12 years between -0.1% and 380%.

- About 5.83 million people, almost half of South Sudan’s population, are experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity classified as IPC Phase 3 or above (Crisis or worse) between September to November 2023.

- Since the outbreak of fighting in Sudan on April 15, 2023, there’s been an influx of people fleeing the country with more than 434,000 people recorded as crossing the border into South Sudan as of Dec. 11, 2023, and more people expected to arrive as the fighting continues.

- One million people have been affected by four consecutive years of flooding that have submerged an area larger than Denmark.

- To address the most critical needs of 6.8 million people, the 2024 HRP will require $1.8 billion and “Without this support, peoples’ vulnerability risks further deterioration.”

- South Sudan’s 2024 Regional Refugee Response Plan requires $1.5 billion to meet the critical needs of more than 2.3 million refugees and asylum seekers and 2.4 million members of their host communities.

- As of Jan. 31, 2024, there were 2,269,893 South Sudanese refugees hosted in neighboring countries, with Uganda hosting 40.9% (926,550) of the total figure.

Conflict and violence

South Sudan remains one of the least peaceful countries in the world, according to the 2023 Global Peace Index. South Sudan experienced a 1% deterioration of its overall score in the 2023 report, owing to deteriorations in the “ongoing conflict” and “militarization” domains.

South Sudan’s latest peace agreement, the Revitalized Agreement on the Resolution of Conflict in South Sudan (R-ARCSS), was signed in 2018. The agreement led to a fragile truce and resulted in the formation of the Transitional Government of National Unity in February 2020.

In March 2023, President Kiir appointed a member of his own party as defense minister. The move breaches part of the peace deal in which the position should be selected by the party of First Vice President and opposition leader, Riek Machar.

It is widely expected that the first general national elections will be held in South Sudan in December 2024, followed by the conclusion of the transitional arrangements set out and agreed to in the R-ARCSS.

Amnesty International documented potential war crimes and other violations during the fighting in Western Equatoria in 2021. The various forms of violence threaten and undermine people’s physical and mental well-being.

In September 2022, a UN human rights team said incidents of rape had become so common in South Sudan that many women no longer report repeated sexual attacks. Rape victims lack access to medical and trauma care.

Community leaders and other individuals involved in peacebuilding work in South Sudan were interviewed by The New Humanitarian and called for long-term initiatives that build positive ties between communities that have been divided by a civil war that cleaved groups along ethnic lines.

South Sudan continues to be one of the most dangerous places for aid workers. On Nov. 6, 2023, a South Sudanese national aid worker was killed while on a field trip to respond to a suspected measles outbreak in the Greater Pibor Administrative Area.

In January 2024, 52 people, including women and children, were killed in the Abyei region, a disputed region between Sudan and South Sudan. A Ghanaian peacekeeper from the United Nations Interim Security Force for Abyei was killed when the base in Agok town was attacked. The UN said following the attacks that armed youth from rival factions of the Dinka ethnic group have been battling over the location of an administrative boundary in the oil-rich region.

Exacerbating the humanitarian situation in South Sudan is the fighting that erupted in neighboring Sudan in mid-April between the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces. More than 475,000 people were recorded as crossing the border into South Sudan as of Dec. 31, 2023. The majority are South Sudanese returnees who have been residing in Sudan.

In addition to causing significant displacement, the fighting on both sides of the border is complicating and reducing humanitarian access. Although December 2023 saw a slight decrease in the number of reported incidents related to humanitarian access constraints throughout the country compared to November, “bureaucratic impediments, operational interferences and active hostilities resulted in violence against humanitarian staff.”

Thousands of people fleeing to South Sudan pass through the town of Renk, where the humanitarian situation is dire. The Renk Transit Centre was designed to accommodate around 4,000 people, but more than 23,000 are staying there. Water and sanitation services are insufficient in Renk, and cases of cholera, measles and severe malnutrition are on the rise.

The UN envoy for South Sudan, told the UN Security Council in June 2023 that the humanitarian, economic and political impacts of the Sudanese fighting are exacerbating “the existing triggers and drivers of conflict” in South Sudan, and are “complicating an already tenuous security situation across the country.”

In November 2023, the UN Special Envoy for the Horn of Africa Hanna Serwaa Tetteh told the UN Security Council the conflict in Sudan “is profoundly affecting bilateral relations between Sudan and South Sudan, with significant humanitarian, security, economic and political consequences that are a matter of deep concern among the South Sudanese political leadership.”

Flooding

South Sudan is facing its worst flooding in decades. Four consecutive years of record-breaking rains and floods covered two-thirds of the country and left people without food or land to cultivate. The devastating flooding damaged shelters and schools, destroyed crops and household goods, reduced access to safe water and hindered humanitarian access.

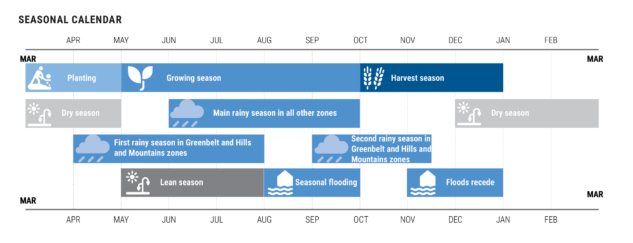

December to February are typically the driest months for South Sudan, when the rivers subside and the Sudd wetlands air out. For more details on South Sudan’s seasonality, refer to the image below. The water from the previous floods is not receding before the next rains come. Dr. Liz Stephens, professor in climate risks and resilience at the University of Reading, said, “It will certainly take years for the floods from 2021 to recede, because the land is disconnected from the main river, so floodwaters have to evaporate rather than drain away.”

The effects of the flooding are severe and broad. In 2021, the flooding destroyed 161,055 acres (65,177 hectares) of agricultural land and killed 795,558 livestock. In 2022, flooding affected over 900,000 people, displacing 140,000 people across 29 counties.

According to UNOCHA in June 2023, “These recurring floods have worsened an already dire situation, leaving people without food and viable land for cultivation. The same states affected by severe flooding are now receiving refugees and returnees from Sudan, further straining the capacity to respond.”

Flooding also directly affects access to potable groundwater, movement of conflict-affected populations, livestock and human health and safety and movement of humanitarian aid.

In August 2023, the southern side of Renk experienced localized flooding, which displaced an estimated 1,750 people in Renk town and significantly affected the surrounding areas. As of November 2023, about 15% of the country is submerged year-round, as opposed to 5% several years ago.

Many people who lost their 2021 harvest lost their livestock due to diseases caused by animals grazing on flooded fields. Collecting and eating plants is one coping strategy people have used. Thousands of people are being forced to move, perhaps permanently, from their traditional lands. With South Sudan already experiencing ethnic tensions and subnational conflict over resources, large scale displacements caused by flooding are likely to exacerbate the situation as people move into new lands.

In 2020, South Sudan announced a plan to have state-owned Nile Petroleum Corp take over oil production when existing operators’ contracts expired. In February 2023, South Sudan’s Minister of Petroleum said the country’s oil production dropped to 140,000 barrels per day from 160,000 barrels per day in 2022 due to heavy flooding in the northern oil fields. Oil production, along with agriculture, are the most important sectors of South Sudan’s economy, with oil contributing 90% of revenue, according to the World Bank.

Displacement

Critical drivers of displacement in South Sudan are conflict, persistent poverty, food insecurity and flooding. As of the end of December 2023, there were two million IDPs in South Sudan, and more than 2.26 million South Sudanese are refugees in neighboring countries as of Jan. 31, 2024.

Of the five neighboring countries hosting South Sudanese refugees, Uganda hosts the most at nearly 41%. Most refugees are situated in remote and economically underserved areas. Host communities are often in an unstable socioeconomic situation themselves, and new refugees’ arrival could further exacerbate hardship.

Many displaced people have been forced to relocate multiple times to seek better living conditions or flee violence, particularly as those South Sudanese who fled northward into Sudan have again been displaced by violence and conflict there. Women, girls and people with disabilities are at risk of sexual violence, both inside displacement sites and when collecting fuel or food in surrounding areas.

A macroeconomic crisis, linked to a decade of conflict, is a driver of South Sudan’s humanitarian crisis and contributes to displacement. The 2023 Global Report on Food Crises highlighted other drivers of the crisis, including very high staple food prices that are a result of insufficient domestic food supplies; low foreign currency reserves and the weak national currency; high fuel prices; and reduced imports from neighboring Uganda. These factors result in limited access to livelihoods, lack of agricultural opportunities and continued insecurity, which forces people to flee their homes in search of safety and food assistance.

According to South Sudan’s 2023 Regional Refugee Response Plan (RRRP), “Some of the vulnerabilities and risk stem from exposure to endemic violence and the impact of climate chocks in the country of origin and others are magnified by prolonged displacement in situations where the needs outstrip the available resources for assistance, compounded by environments not conducive to self-reliance.”

The refugee crisis is a children’s crisis; children between the ages of 0-17 make up over 50% of the population, according to the 2023 RRRP. Refugee children face particular risks, including child labor, abduction and exposure to being trafficked.

Food insecurity

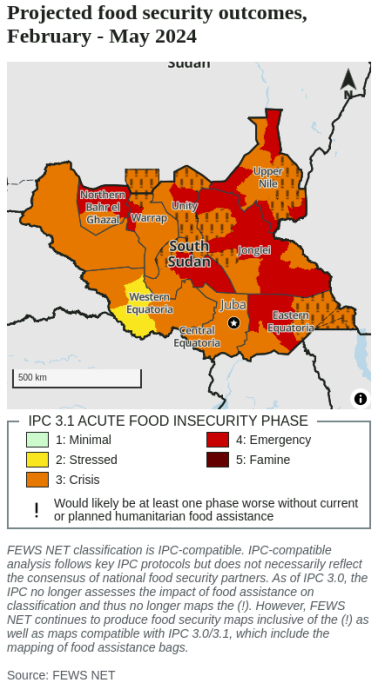

In December 2023, acute food insecurity remained high in South Sudan. The flooding and dry spells combined with currency depreciation, high food prices, conflict and insecurity are driving factors.

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) is a common scale for classifying the severity and magnitude of food insecurity and acute malnutrition. The scale includes five phases, with Phase 1 meaning there is no or minimal acute food insecurity and Phase 5 meaning famine has been reached.

In their January 2024 South Sudan Key Message Update, FEWS NET said Crisis (IPC 3) outcomes are expected to continue across the country, with Emergency (IPC 4) outcomes projected to grow from 22 to 28 counties.

According to FEWS NET, this deterioration in food security outcomes is “due to protracted negative impacts of conflict and poor macroeconomic conditions, compounded by high returnee burden and faster-than-normal depletion of household food stocks.”

A WFP and Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN report released in May 2023 said, “The eruption of armed conflict in the Sudan in April 2023 is likely to have significant ramifications for its neighbouring countries, in particular large population movements and increasing levels of acute food insecurity among displaced and returning populations, and host communities across several regions.”

The combined effects of devastating flooding, linked to climate change, and armed conflict have reduced agricultural production, led to a loss of livelihoods and destroyed household assets. The WFP warned in November 2023 that children in flood-affected parts of South Sudan are expected to face extreme levels of malnutrition in the first half of 2024 “as the climate crisis tightens its grip on the country.”

Poor health outcomes

South Sudan’s poor health indicators are due to limited access to health services, shortage of health workforce and inadequate health infrastructure.

Most of the neglected tropical diseases in South Sudan are endemic, posing a serious health threat. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), more than 12 million people are at risk of infection from neglected tropical diseases which cause pain, disabilities and other impacts. Such diseases include elephantiasis, onchocerciasis or river blindness, schistosomiasis or bilharzia, and other skin infections.

South Sudan’s Ministry of Health (MoH) declared a Yellow Fever outbreak in Yambio County, Western Equatoria State. On Dec. 7, 2023, the MoH confirmed an imported case of cholera in the Renk Transit Center following an active outbreak in Sudan.

On Feb. 13, 2024, the MoH, along with WHO and other partners, announced a Yellow Fever vaccination campaign.

The country is also battling a measles outbreak. As of week 45 in 2023, more than 7,000 suspected cases were reported, with 534 lab-confirmed and 152 deaths.

During a complex humanitarian emergency, immediate needs include shelter, food, water, sanitation and hygiene, health care and protection of at-risk populations. These needs will continue through the course of the CHE.

Food assistance and livelihood support

Despite rising needs amid the continued arrival of South Sudanese refugees and returnees in the north, humanitarian assistance is not sufficient. After walking for days with little food and water to reach South Sudan, there is not enough food and water for them at the Renk Transit Center.

According to FEWS NET in September 2023, large funding shortages “are likely to threaten coverage and are already driving difficult prioritization decisions across South Sudan, as evidenced in the decision to suspend assistance for 4 months in Bentiu camp, reportedly due to a funding shortfall.”

In November 2023, Oxfam said people need more than food, “but good governance, just society and opportunities to thrive as we promote resilience programming.” Oxfam concluded by saying, “We are concerned that, should there be any gaps in funding and initiative to maintain peace across the country, the current gains will be entirely lost, and a relapse may be eminent.”

The severity of food security and livelihood needs are concentrated in the same areas most affected by flooding. Hundreds of thousands of livestock were lost due to the floods, which is devastating given the importance of livestock for many people’s livelihoods and sustenance in South Sudan. Replacing livestock and diversifying livelihood opportunities is needed.

Physical and mental health

South Sudan’s health system is among the poorest in the world. There is a severe shortage of trained health professionals. There are growing demands for basic health care services, and flooding threatens the already fragile health system in the country.

The 2024 South Sudan HNRP says 6.3 million people need health services and assistance. In 2024, the health cluster will focus on providing “quality basic primary health care services and prevent health risks while strengthening the health care system.”

At-risk populations, including women, children, older people and persons with disabilities, have limited access to health care and face heightened risks of illness and mortality.

The arrival of thousands of people in South Sudan fleeing the conflict in neighboring Sudan strains the health system further and stretches humanitarian resources. The NGO Médecins Sans Frontières said in October 2023, “Many people, especially children, are arriving at the border with alarming health conditions, suffering from deadly diseases like measles or malnutrition that require immediate medical care.”

The threat of disease is high among those fleeing the conflict in Sudan. Dr Ernest Apuktong, the Upper Nile state’s health minister said in June 2023, “The huge population of returnees and refugees has resulted in overcrowding at the transit sites, posing a serious risk of disease outbreaks.”

Years of conflict and the impact of COVID-19 have resulted in trauma and mental health conditions for a large proportion of the country’s population. Despite mental health and psychosocial concerns, access to mental health and psychosocial support remains lacking and is urgently needed along with life-skills education.

Protection

South Sudan remains a protracted protection crisis, with women and girls continuously at risk of being attacked while carrying out their daily routines as they care for their families’ needs. Gender inequality and disability exclusion in the country allow for the continued marginalization of at-risk groups, particularly women, girls, LGBTQI+ individuals and people with disabilities.

Ensuring the protection of affected people requires an understanding of protection mainstreaming principles. The South Sudan Protection Cluster provides information and updates on humanitarian partner activities.

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH)

According to the 2024 South Sudan HNRP, 5.6 million people will require WASH assistance. Among the worst affected areas is Manyo in Upper Nile State, where 99% of the population lacks access to improved water sources and 96% lacks improved sanitation facilities.

Already limited resources are strained by the compounding challenges of displacement, insecurity, flooding, economic difficulties and the influx of people returning from Sudan. In some counties, women and girls travel more than 30 minutes to reach water sources, making them vulnerable to gender-based violence.

In 2024, the WASH cluster will make some minimal hardware improvements where possible, rehabilitate existing water systems, complete water testing, distribute WASH-related items and promote safe hygiene practices. In flood-prone and flood-affected areas, any infrastructure repairs or improvements should account for flood risk in planning and ensure resilient infrastructure investments are made.

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy has a Global Recovery Fund that provides an opportunity for donors to meet the ongoing and ever-expanding challenges presented by global crises.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you have questions about donating to the CDP Global Recovery Fund, need help with your disaster-giving strategy or want to share how you’re responding to this disaster, please contact development.

(Photo: IDPs in the capital of South Sudan relocate to a cleaner, drier location across town, under the protection of the United Nations Mission in South Sudan. Source: UN Photo/Isaac Billy; CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO, please send updates on how you are working on this crisis to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Philanthropic and government support

Grants from the philanthropic community vary in size, focus and sector. The following are examples of the diversity of philanthropy’s response:

- Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) provided $750,000 through its COVID-19 Response Fund to Save the Children for the Local Response Pooled Fund in South Sudan. This pooled funding mechanism transfers resources and decision-making power over funding decisions to local actors. The project will fund 11 South Sudanese organizations to meet the most critical COVID-19-related humanitarian needs in remote and hard-to-reach areas of the country.

- CDP provided $250,000 through its Global Recovery Fund to the Near East Foundation to provide immediate, life-saving support to at-risk, crisis-impacted people in South Sudan and Sudan. The project will reduce the risk of food insecurity, recover livelihoods and build resilience to future shocks through improved agricultural production, inclusive value chain development and access to finance.

- Open Road Alliance provided $100,000 to CORE Group to support their COVID-19 response.

- Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation provided $291,200 to Adeso to support the development and implementation of actions that promote exchange, sharing, learning and coordination of COVID-19 related topics.

- The UN Trust Fund to End Violence Against Women provided $206,769 to Strategic Initiative for Women in the Horn of Africa to promote positive changes in attitudes, behaviors and practices to end sexual violence against women and girls in four camps for IDPs.

The HNRP 2024 for South Sudan seeks $1.8 billion to target six million of the nine million people estimated to be in need of humanitarian assistance. South Sudan’s 2023 HRP requested $1.7 billion to meet the needs of 6.8 million people targeted for assistance. As of Nov. 11, 2023, donors had funded just 53.8% of the 2023 HRP.

On July 7, 2022, the U.S. announced it would provide the country with an additional $117 million in humanitarian assistance. On Aug. 4, 2022, the U.S. announced an additional $106 million for the WFP. An investment of $43.5 million in youth development in the country was announced by the U.S. on Nov. 16, 2022. The U.S. Agency for International Development said on Feb. 22, 2023, that it would provide $3 million for agriculture resilience programs in South Sudan.

In response to the possible spill-over of Sudan’s cholera epidemic into South Sudan, the European Union announced on Dec. 22, 2023, new funding of over $646,000 (€600,000) to South Sudan to help the country prepare and respond to the outbreak.

More ways to help

As with most disasters and emergencies, cash donations are recommended by disaster experts as they allow for on-the-ground agencies to direct funds to the most significant area of need, support economic recovery and ensure donation management does not detract from disaster recovery needs.

Donors can help in the following ways:

- Provide unrestricted core funding for vetted humanitarian NGO partners that support the HNRP 2024. This is an efficient way to ensure the best use of resources in a coordinated manner. Funding the NGOs that have contributed to the HRP ensures that resources are directed to support the plan and use humanitarian partners’ best knowledge.

- Prioritize investments in local organizations. Local humanitarian leaders and organizations play a vital role play a vital role in providing immediate relief and setting the course for long-term equitable recovery in communities after a disaster or crisis. However, these leaders and organizations are mostly under-resourced and underfunded. Grant to locally-led entities as much as possible. When granting to trusted international partners with deep roots in targeted countries, more consideration should be given to those that empower local and national stakeholders.

- Understand that recovery is possible in protracted and complex crisis settings. Even while focusing on immediate needs, remember that there are early and long-term recovery needs, too. We know that people who have been affected by shocks in complex humanitarian contexts can recover and improve their situation without waiting until the crisis is over, which may take years. Recovery is possible, and funding will be needed for recovery efforts alongside humanitarian funding. Recovery will take a long time, and funding will be needed throughout.

- Recognize there are places and ways that private philanthropy can help that other donors may not. Private funders can support nimble and innovative solutions that leverage or augment the larger humanitarian system response, either filling gaps or modeling change that, once tested and proven, can be taken to scale within the broader humanitarian response structure. Philanthropy can also provide sustainable funding to national and local organizations.

Resources

Complex Humanitarian Emergencies

CHEs involve an acute emergency layered over ongoing instability. Multiple scenarios can cause CHEs, like the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the man-made political crisis in Venezuela, or the public health crisis in Congo.

Floods

Flooding is our nation’s most common natural disaster. Regardless of whether a lake, river or ocean is actually in view, everyone is at some risk of flooding. Flash floods, tropical storms, increased urbanization and the failing of infrastructure such as dams and levees all play a part — and cause millions (sometimes billions) of dollars in damage across the U.S. each year.

Resilience

The Latin root of “resilience” means to bounce back, but every field has its own definition and most individuals within each discipline will define it differently. Learn more.