Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

Hurricanes, also called typhoons or cyclones, bring a triple threat: high winds, floods and possible tornadoes. But there’s another “triple” in play: they’re getting stronger, affecting larger stretches of coastline and more Americans are moving into hurricane-prone areas.

Overview

Hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones pose significant global threats to life and property, including storm surges, flooding, extreme winds and tornadoes.

Additionally, rainfall rates are projected to increase in the future due to anthropogenic warming and accompanying increase in atmospheric moisture content.

According to the National Hurricane Center (NHC), “A tropical cyclone is a rotating, organized system of clouds and thunderstorms that originates over tropical or subtropical waters and has a closed low-level circulation.”

Hurricanes, cyclones and typhoons are different terms for the same weather phenomenon. The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) describes the terms in the following manner:

- “In the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico, the North Atlantic Ocean and the eastern and central North Pacific Ocean, it is called ‘hurricane.’

- In the western North Pacific, it is called typhoon.

- In the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea, it is called cyclone.

- In western South Pacific and southeast Indian Ocean, it is called severe tropical cyclone.

- In the southwest Indian Ocean, it is called tropical cyclone.”

As a storm moves across the ocean, it picks up warm, moist air from the surface and dispenses cooler air aloft. As the storm makes landfall, it loses momentum, no longer fueled by the warm ocean air. Winds of up to 185 miles per hour are just one damaging aspect. Drenching rains can cause heavy flooding inland. Wind-driven storm surges also can dangerously inundate low-lying areas.

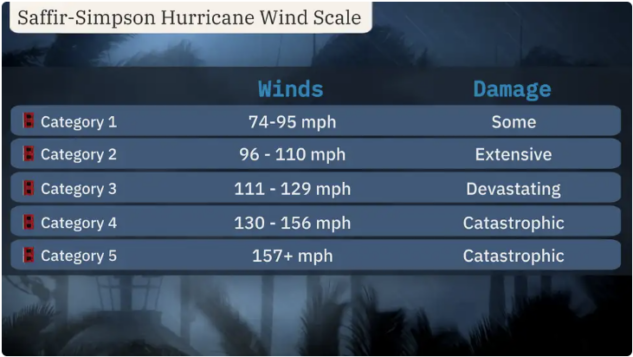

The Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale is a one to five rating based on a hurricane’s maximum sustained wind speed. However, this rating system faces some controversy because it does not always capture the storm’s full potential impact, which may be caused by rain and flooding. This rating system does estimate potential property damage.

Hurricane Ida is an example of a cyclone that demonstrated repeated cycles of strengthening and weakening as it moved across a large geographic area from Cuba to Louisiana to New York. Ida produced a devastating storm surge that moved inland from the immediate coastline across portions of southeastern Louisiana. Most hurricanes quickly weaken upon landfall, but Ida remained a major hurricane for nine hours. As the world warms, it is expected that more tropical systems will use the warmer water to intensify rapidly. Ida went from showers to a 150-mile-per-hour hurricane in three days.

Rapid intensification of tropical systems is a growing concern. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) defines rapid intensification as a storm that increases by 35 miles per hour within a 24-hour period. In 2022, Hurricane Ian grew from a tropical storm to a Category 3 hurricane within 36 hours. It then grew to a Category 4 the next day – gaining 35 miles per hour within just three hours – and reached Category 5 strength a few hours later. Similarly, in September 2022, on the other side of the world, Typhoon Noru grew from a Category 1 equivalent to a Category 5 equivalent in just six hours, leaving residents of the Philippines no time to prepare or evacuate.

A tropical cyclone may occur somewhere in the world throughout the year.

- The typhoon season in the western North Pacific region typically runs from May to November.

- The Americas/Caribbean hurricane season runs from June 1 to November 30, peaking in August and September.

- The cyclone season in South Pacific and Australia normally runs from November to April.

- In the Bay of Bengal and Arabian Sea, tropical cyclones usually occur from April to June, and September to November.

- The East Coast of Africa normally experiences tropical cyclones from November to April.

However, out-of-season storms do occur. Discussions among experts are ongoing about whether the start and end dates of these traditional seasons need to be revised.

Hurricane forecasting continues to improve in accuracy and in its ability to provide advance warning. However, it remains an inexact science because of the number of factors that can influence a hurricane’s direction and strength, including wind speed, size, rainfall and duration.

In the U.S., the NHC provides the public and its partners with information on tropical weather, including forecasts. The NHC is a division of NOAA and is located at Florida International University in Miami, Florida.

The NHC uses many models in the preparation of forecasts. However, they state, “Users should also be aware that uncertainty exists in every forecast, and proper interpretation of the NHC forecast must incorporate this uncertainty.”

Globally, early-stage formation is monitored by WMO through its World Weather Watch and Tropical Cyclone Programmes. WMO regional centers provide, in real-time, advisory information and guidance to the National Meteorological Services. The National Meteorological Services of countries then issue official warnings.

Key Facts

- To be classified as a hurricane, typhoon or cyclone, tropical systems must reach wind speeds of at least 73 miles per hour (118 kilometers per hour). If winds speeds are below 73 miles per hour, the storms are classified by different terminology based on the location. For example, in the North Atlantic and northeast Pacific, a storm with winds speeds less than 73 miles per hour is called a tropical storm or a tropical depression if wind speeds are 32 miles per hour (62 kilometers per hour) or less.

- Tropical cyclones produce widespread and devastating impacts. Historically, the costliest disasters have been hurricanes, often those occurring in the U.S., and earthquakes. Hurricane Ian hit the U.S. in 2022 causing damages worth $100 billion, making it the costliest disaster event globally that year. In 2023, storms caused the second most fatalities of any disaster type according to the Emergency Event Database EM DAT.

- More people are living in harm’s way. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, 129 million people, or almost 40% of the total U.S. population, lived in coastline counties in 2020. Nearly 22% of individuals living in coastal shoreline counties show at least three components of social vulnerability, as defined by the U.S. Census Community Resilience Estimates (excluding the U.S. territories). The Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University says around 40% of the world’s population lives within 62 miles (100 kilometers) of the coast. The world is urbanizing, and coastal cities face worrying levels of exposure vulnerability to natural hazards, including tropical cyclones.

- Tropical cyclones are increasing in intensity because of climate change. Heat trapped by greenhouse gases released by human activities gets stored in oceans, providing additional fuel for hurricanes. Major tropical cyclones pose a significant threat to life and property, and studies suggest that increased tropical cyclone intensity is likely under continued warming.

- Tropical cyclones can produce health impacts. According to the World Health Organization, tropical cyclones may affect health in many ways, such as increasing risks of water-borne diseases, increasing mental health effects, and disrupting health systems. A 2022 study found that hurricanes and other tropical storms in the U.S. were associated with up to 33.4% higher death rates in subsequent months. Tropical cyclones, including hurricanes, can also cause people to experience emotional distress.

- Tropical cyclones bring more rainfall, increasing flood risks. Because warmer air contains more moisture, as surface temperatures rise, rainfall rates are increasing. In addition, changes in circulation patterns cause hurricanes to move slower, meaning more rainfall in a single location, as with Hurricane Harvey in 2017. The National Weather Service had to add two shades of purple to its map to show the amount of rainfall due to Harvey. Hurricane Florence was only a Category 1 hurricane when it made landfall in North Carolina in September 2018, but the slow-moving storm brought heavy rain to the Carolinas, flooding tens of thousands of homes.

How to Help

- Invest in local organizations. In the U.S., long-term recovery groups provide coordinated services to enable everyone to recover. Building the capacity of such organizations with a long-term presence at the local level helps ensure preparedness and recovery efforts are contextually relevant and effective. Local communities and actors know their context and needs best. Outside the U.S. localization is a term used to describe the process of recognizing, respecting and strengthening local capacity to better address the needs of affected people.

- Support tropical cyclone preparedness. Creating evacuation plans, assembling disaster supplies and retrofitting homes can help lessen the impact of a tropical storm. Preparedness support is essential for low-income individuals and marginalized populations. Ensure that communication materials are culturally appropriate and in the local population’s preferred language(s).

- Support mental health and psychosocial support programs. Not all tropical cyclone damage is visible. Exposure to hurricanes is a risk for new-onset major depression, generalized anxiety disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder. Mental health support and care are needed in preparedness and recovery. This is particularly true in areas that have experienced multiple storms.

- Fund efforts to protect and improve natural barriers in coastal areas. Natural features such as marshes, wetlands, mangroves and coral reefs are a primary line of defense against the coastal hazards of hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones. In Louisiana, the Coastal Master Plan has provisions to create or restore almost 34,000 acres of marsh that make up a land bridge buffer. According to the World Bank, integrating “green” infrastructure, such as mangroves, with traditional “gray” infrastructure like embankments can provide cost-effective protection from tropical cyclones.

What Funders Are Doing

- The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) has a standing Atlantic Hurricane Season Recovery Fund. CDP also makes grants in support of tropical cyclone recovery and preparedness through the Global Recovery Fund, the Disaster Recovery Fund and in partnership with Google. The following are examples of related grantmaking.

- $300,000 to Robeson County Disaster Recovery Committee, the long-term recovery committee for several adjoining counties in North and South Carolina, to sustain their work advancing survivors’ recovery from multiple disasters dating back to Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

- $250,000 to Casa Juana Colon to provide recovery and mitigation support to the most vulnerable people in the communities in Comerío, Puerto Rico on issues related to health and food security. The grant will help prepare the organization to activate in the face of the next disaster.

- $57,500 to VIA LINK to replicate and improve upon their Hurricane Ida data tool dashboard for the Florida Alliance of Information and Referral Systems, Florida’s 211 network. The project will support social services agencies and other community resources in equitable recovery from Hurricanes Ian and Idalia.

- $300,000 grant to Vibrant Emotional Health to sustain and expand its disaster behavioral health training and preparedness program to support local disaster-responding organizations throughout the U.S.

- $188,378 to Guakia Ambiente to recover from the aftermath of Hurricane Fiona and enhance water security and resilience through the use of photovoltaic solar energy to power water pumping stations in El Seibo province, Dominican Republic. The project adopts a build back better approach and focuses on resilience, community-centered design and implementation, and capacity strengthening.

- $98,872 to Philippine Disaster Resilience Foundation to restore livelihoods through providing resilient livelihood starter kits and training on boat building to fishing communities affected by Typhoon Odette in Siargao and Dinagat islands. The project provided boat molds and technical knowledge to the community for the continuation of repairs.

- $100,000 to Grand Bahama Resilience Center to scale up mental health support and community cohesion programs, creating a holistic approach to long-term recovery that addresses the interconnected challenges of resilience. By prioritizing mental well-being and adopting adaptive strategies, it aimed to build a resilient community capable of buffering the impacts of climate change and fostering enduring recovery.

- In 2022, The Walmart Foundation made an investment of more than $3 million in a group of organizations helping local government leaders and community-led organizations in the Gulf Coast prepare their communities for disasters.

- The Gulf Coast Community Foundation provided more than $3 million in immediate relief to organizations working in areas hard hit by Hurricane Ian. The grants focused on health and human service needs in southern Sarasota County including Venice, North Port, Englewood, Charlotte County, Lee County and DeSoto County.

- The Community Foundation of Sarasota County (CFSC) activated the Suncoast Disaster Recovery Fund to address long-lasting impacts of Hurricane Ian on people’s lives. The fund supports Sarasota, Manatee, DeSoto and Charlotte Counties for disaster recovery to improve individual, family and community resiliency. The Patterson Foundation strengthened the fund by providing an immediate $500,000 gift to catalyze donor support and a match for all donations up to $750,000. CFSC took time to listen to local organizations and community leaders, which informed what the foundation will focus their resources on to support long-term recovery.

Learn More

- CDP Issue Insight: Disaster Phases

- CDP Issue Insight: Resilience

- The National Hurricane Center (NHC)

- NHC: Cone of Uncertainty

- Ready.Gov: Hurricanes

- NHC: Worldwide Tropical Cyclone Centers

- Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology: Tropical Cyclone Knowledge Centre

- United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction: Cyclone

- World Health Organization: Tropical Cyclones

- World Meteorological Organization: Tropical Cyclones

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Hurricanes and Tropical Storms

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.