Disaster Phases

Disasters affect millions of people and cause billions of dollars in damage globally each year. To help understand and manage disasters, practitioners, academics and government agencies frame disasters in phases.

Overview

Disasters are serious disruptions of the functioning of a community or a society at any scale due to hazardous events interacting with conditions of exposure, vulnerability and capacity, leading to loss and impact. Disasters affect millions of people and cause billions of dollars in damage globally each year.

To help understand and manage disasters, practitioners, academics and government agencies frame disasters in phases. Share on X

The phases of disaster include:

- Mitigation: The National Disaster Recovery Framework describes mitigation as the “capabilities necessary to reduce loss of life and property by lessening the impact of disasters.” Examples include hazard-resistant construction and improved environmental and social policies and public awareness. In climate change policy, the term mitigation is defined differently and is used for the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions that are the source of climate change.

- Preparedness: According to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR), preparedness is “the knowledge and capacities developed by governments, response and recovery organizations, communities and individuals to effectively anticipate, respond to and recover from the impacts of likely, imminent or current disasters.” In practice, preparedness can include early warning systems, contingency planning, stockpiling of equipment and supplies, and creating coordination mechanisms.

- Recovery: The Center for Disaster Philanthropy defines recovery as the process of improving individual, family and community resiliency after a disaster. Recovery is not only about the restoration of structures, systems and services. A successful recovery is also about addressing sources of inequitable and unjust outcomes, and individuals and families being able to rebound from their losses and sustain their physical, social, economic, mental, emotional and spiritual well-being. This phase also seeks alignment with the principles of sustainable development and removing needs by reducing risks and vulnerability.

- Response: UNDRR defines response as “actions taken directly before, during or immediately after a disaster in order to save lives, reduce health impacts, ensure public safety and meet the basic subsistence needs of the people affected.” Response is predominantly focused on immediate and short-term needs and is sometimes called disaster relief. Disaster response should consist of putting into action disaster risk-informed preparedness measures.

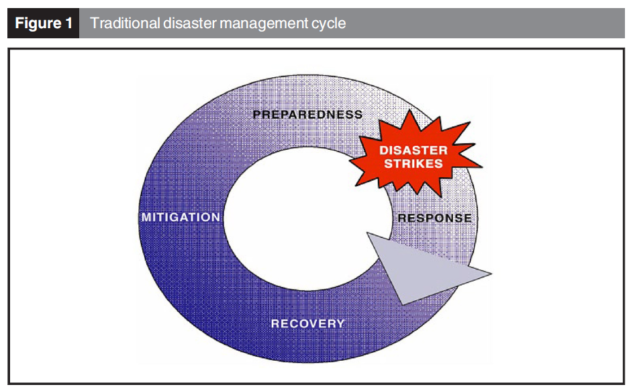

The disaster phases have traditionally been visualized in what is referred to as the “disaster cycle” or “disaster management cycle.” As the name suggests, the “cycle” refers to a cyclical process that includes a disaster event which is then followed by response, recovery, mitigation and finally, preparation activities prior to the next disaster.

The disaster cycle has been criticized for framing disasters in an overly simplistic way that starts with a disaster and ends with another one. According to Sawalha, “In response to the increasing impacts and frequency of disasters and in view of the above complexities in dealing with major incidents, the traditional disaster management cycle has to be revisited and revised.”

Disasters are complex and non-linear and are almost always the result of human actions and decisions. While hazards are natural, disasters are not. Share on X Disasters occur when a natural hazard, such as an earthquake, interacts with human society, particularly vulnerable groups. This concept is visualized in what is known as the pressure and release model. Therefore, humans also possess the ability to alter disaster events.

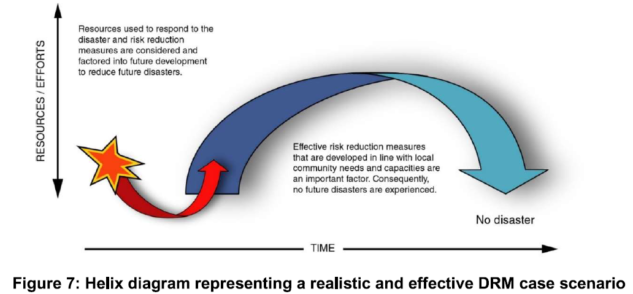

Lee Bosher and colleagues argue that “the problem with the disaster cycle from a holistic DRM [disaster risk management] perspective is that the disastrous ‘event’ is ever present as it starts/ends the cycle of phases. Ideally, effective DRM (where risk reduction measures are suitably taken on board) would result in the elimination of a disaster ‘event’ as it would address not only the physical manifestation of a disaster ‘event’ but its systemic root causes.”

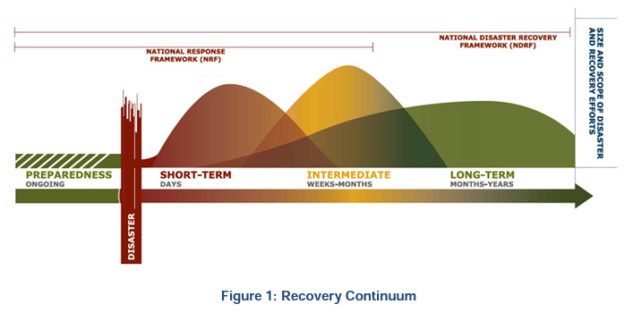

Several researchers and practitioners have observed that rather than siloed or cyclical, the disaster phases are interconnected and overlap with and influence one another. Such thinking is seen in the Recovery Continuum as described in the second edition of the National Disaster Recovery Framework (NDRF). According to the NDRF, “The Recovery Continuum highlights the reality that, for a community faced with significant and widespread disaster impacts, preparedness, response, and recovery are not and cannot be separate and sequential efforts.”

Although use of the traditional disaster cycle persists, discussions are ongoing and new models are emerging that aim to reimagine the cycle in a way that considers the phases of disaster as dynamic and interconnected processes. One such example is the helix diagram from Lee Bosher and colleagues which “provides a new way in which DRM can be understood. Instead of linear stop-start activities, the DRM helix suggests that the actions of DRM must be understood in complex linked systems.”

The version of their diagram shown below represents a “realistic and effective DRM case scenario” where the disaster does not have a major impact, leading to small response and recovery activities while also initiating risk reduction activities that may lead to a future of no additional disasters.

Key Facts

- The number and intensity of disasters are increasing. In a 2020 report comparing the period of 2000-2019 to 1980-1999, UNDRR found the number of major floods around the world more than doubled, from 1,389 to 3,254. According to a 2021 report from the World Meteorological Organization, the number of disasters globally increased by a factor of five over the past 50 years, driven by climate change. In the U.S., the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the increase in frequency and diversity of billion-dollar disasters is concerning because “it hints that the extremely high activity of recent years is becoming the new normal.” Humanitarian needs and funding requirements globally are also on the rise.

- Most of philanthropy’s disaster-related funding goes to response and relief. According to the 2021 Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy report, a joint effort between CDP and Candid, 51% of philanthropic funding for disasters in 2019 went towards response and relief activities. The report revealed that only 17% was spent on preparedness, 6% on recovery and 4% on resilience, risk reduction and mitigation. To maximize impact and reduce the effect of disasters, funders should invest more in recovery, preparedness, mitigation and resilience. The 2022 report found that only a small percentage was invested in all of the areas outside of response and relief in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Investing in risk reduction and prevention saves money. As the frequency and intensity of disasters globally increase, the need to invest in reducing disaster risk becomes more urgent. A 2020 study by the National Institute of Building Sciences (NIBS) found that mitigation can save up to $13 per $1 invested. The largest returns on investment are seen with earthquake hazard mitigation measures but positive returns are outlined in the NIBS study across flood, wind and hurricane surge as well. According to UNDRR, every $1 invested in risk reduction and prevention can save up to $15 in post-disaster recovery. Yet UNDRR says for every $100 of disaster-related assistance, just 50 cents are invested in protecting development from the impact of disasters.

- Preparedness is effective and saves lives. When Cyclone Bhola hit present-day Bangladesh in 1970, between 300,000 to 500,000 people were killed. Since 1970, Bangladesh’s population has doubled, and a warming climate has brought more frequent extreme events. Yet, the South Asian country has reduced its cyclone-related deaths more than a hundredfold due to a multi-layered early warning system, a large volunteer program and education. UNDRR has documented practical examples of how risk-informed preparedness contributes to saving lives and reducing economic losses.

How to Help

- Support the disaster phases outside response. Since its formation, CDP has encouraged philanthropy to consider all disaster phases in their funding, not just response or relief. Support immediately following a disaster is important, and lifesaving assistance may be required in some contexts, however, philanthropy can have a significant impact by investing in recovery, preparedness, mitigation and resilience.

- Provide funding that is flexible. Investing in partners across the phases of disasters requires flexibility so funds can be used as needed over an extended period. Disasters and complex humanitarian emergencies are complicated and dynamic, meaning the situation and needs shift over time. Flexible funding also develops trust between funders and grantee partners, which is key for effectively working in partnership.

- Prioritize investments in local organizations. Local leaders and organizations play a vital role in providing immediate relief and working towards long-term equitable recovery in communities after a disaster or crisis. However, these leaders and organizations are mostly under-resourced and underfunded. Strive to grant to locally-led entities as much as possible. Internationally, when granting to trusted partners with deep roots in targeted countries, more consideration should be given to those that empower local and national stakeholders.

- Address root causes of vulnerability. Hazards, such as hurricanes, are natural, but disasters are not. The location people live, their racial or socioeconomic status and a government’s public policies are all examples of factors that influence who is affected by a disaster and how catastrophic it is. In short, disasters are socially constructed. Therefore, funders can invest in areas that will improve people’s lives and reduce their vulnerability to disaster. Examples include increasing access to safe and affordable housing, strengthening or diversifying livelihoods and advocating for policy changes that positively impact at-risk and marginalized populations.

What Funders Are Doing

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy has made the following investments that focus on working across the disaster phases.

- In partnership with Google, $301,391 was awarded to Sustainable Environment and Ecological Development Society in 2022 to support communities in meeting the recovery needs of the most marginalized people impacted by the summer 2022 floods in Cachar district of Assam, India. The grant will support the rebuilding of damaged schools, increase access to clean water and build long-term resilience by incorporating DRM practices in the work of multiple stakeholders.

- Through the COVID-19 Response Fund, $450,000 was awarded to ADESO in 2022 to increase access to water for drought relief and to mitigate the risk of COVID-19 spreading in water-scarce communities in northern Somalia. The project’s findings will also enable ADESO to develop a water social enterprise that will provide a long-term, affordable and more sustainable solution to water security.

- Through the Midwest Early Recovery Fund’s Native American and Tribal Communities Recovery Program, $120,000 was awarded to Great Plains Tribal Leaders’ Health Board to build local capacity to respond to, and recover from, disasters in Indian Country through supporting Emergency Operations Centers, preparedness training, food sovereignty and mental wellness.

- Through the Disaster Recovery Fund, $250,000 was awarded to Disaster Leadership Team to support the creation of and provide mentorship to long-term recovery groups that are preparing to manage disaster recovery in their community. The mentorship component lasts for a minimum of one year and at different stages of need.

Other philanthropic investments spanning the phases of disaster include:

- Ford Foundation provided $750,000 to Sonke Gender Justice Network in 2021 for a gender transformative approach to human rights and gender justice work, including support for the financial resilience of the social justice sector in Southern Africa in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation provided $1,497,563 to Asian Disaster Preparedness Center Foundation to strengthen and improve coordination capacity for emergency response of government institutions in Ethiopia.

Learn More

- Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters: Emergency Events Database

- Measuring the State of Disaster Philanthropy: Foundation Maps

- UNDDR: Understanding Risk

- UNDDR: Terminology