Earthquakes

Striking without warning, earthquakes often are among the most devastating disasters. Caused by the movement of plates along fault lines on the earth’s surface, earthquakes often leave a monumental path of instant death and destruction.

Overview

Striking without warning, earthquakes often are among the most devastating natural hazards.

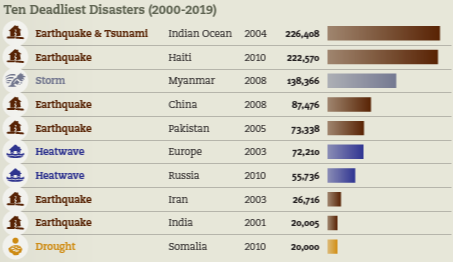

Striking without warning, earthquakes often are among the most devastating natural hazards. Among disaster types, earthquakes represented only 8% of disaster occurrences globally between 2000-2019, however they made up 58% of total deaths during that period according to the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR). The 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami, and the 2010 Haiti earthquake top the list of the deadliest disasters in the first two decades of this century.

In addition to the loss of life, earthquakes can cause massive damage to infrastructure. For example, UNDRR reported the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan resulted in $239 billion in economic losses, the highest figure of any environmental disaster event recorded. Other analysis estimated $211 billion in direct damages from the disaster.

Caused by the movement of plates along fault lines on the earth’s surface, earthquakes often leave a monumental path of instant death and destruction. In some cases, however, the quake is only the beginning of the trouble, such as the tsunami and nuclear meltdown that followed the massive 2011 earthquake in Japan or the 1906 San Francisco earthquake which led to a damaging fire. Some of the world’s most populous cities lie on fault lines including Mexico City, Tokyo, New York City, Mumbai, Delhi, Shanghai, Kolkata and Jakarta.

The Richter Scale is what many people are familiar with, but that scale is outdated and no longer used by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) for large, teleseismic earthquakes. For such large quakes, moment magnitude is considered to provide the most reliable estimate of earthquake size. USGS explains that magnitude “is expressed in whole numbers and decimal fractions. For example, a magnitude 5.3 is a moderate earthquake, and a 6.3 is a strong earthquake.”

In the United States, three significant fault lines have the potential for tremendous damage. The San Andreas Fault, for one, runs the length of California. While the last mega-quake was in 1906, the state has been beset by large earthquakes on a frequent basis. Consequently, the state has somewhat stringent building codes to withstand the shaking.

The Cascadia Subduction Zone in the Pacific Northwest stretches from Seattle to Northern California and experiences a giant quake every 300-600 years; the last was in 1700 according to the USGS. The New Madrid Seismic Zone links Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Tennessee, Arkansas, Missouri and Mississippi. Three earthquakes in excess of a magnitude of 8.0 occurred there in 1811 and 1812; scientists say those quakes likely were larger than the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, though modern measurements did not exist then. Both faults have a significant likelihood of triggering a major earthquake in the next half century.

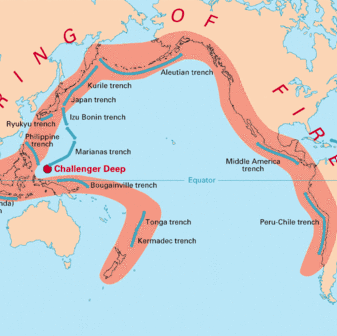

Internationally, the Pacific Ring of Fire is home to 90% of the world’s earthquakes. It is a string of at least 450 active and dormant volcanoes that stretches from the southern tip of South America, up along the North American coast, and down through Japan and into New Zealand. It is an area with high seismic activity. There have been several substantial earthquakes in this area including the May 22, 1960 Valdivia earthquake which, at a magnitude of 9.5, is the largest earthquake ever recorded.

Key Facts

- In the immediate aftermath of an earthquake, affected people are often first responders. Roads, bridges and airports may be disabled and communications systems are often challenged following an earthquake. Emergency aid that can arrive often is focused on search-and-rescue operations. Consequently, many affected find they must provide for their own basic needs for the first few days.

- The aftermath of an earthquake may bring immediate and long-term health impacts, especially in lower middle-income countries. In addition to trauma-related deaths and injuries from building collapse, other health impacts include risk of communicable diseases, increased risk of complications of chronic diseases and increased psychosocial needs. In Haiti, a post-earthquake outbreak of cholera killed more than 10,000. The number is small compared to the loss of life from the earthquake itself, but the cholera outbreak had a long-term impact on the population with transmission continuing into early 2019 and a resurgence in the greater Port-au-Prince area in October 2022.

- Earthquakes can negatively impact economic and development outcomes. Devastation resulting from large earthquakes is often associated with damage to the build environment. However, earthquakes can have other long-lasting consequences. For example, the macroeconomic effects of the 2010 Haiti earthquake “were equal to an average loss of up to 12% of gross domestic product over the period 2010–2015.” Due to their low-intensity high-frequency nature, floods and droughts are responsible for most of the disaster impact on poverty. However, a single earthquake or tsunami can push millions into poverty.

- Countries that strengthen building codes often reduce death and destruction. Local and national governments can play a crucial role in reducing future losses by enacting or modifying building codes. In 2010, Chile and Haiti were struck by strong earthquakes six weeks apart but experienced vastly different impacts resulting from different vulnerability levels. The Chilean earthquake was at least 500 times more powerful than the earthquake in Haiti, yet many more Haitians lost their lives. The lack of hazard-aware land use and building standards in Haiti compared to Chile created the conditions for increased vulnerability and catastrophic impact.

- In the United States, earthquakes are not isolated to one region of the country. In the midwestern and eastern parts of the U.S., the most earthquake-prone areas include Charleston, South Carolina, eastern Massachusetts, the St. Lawrence River area and the central Mississippi River Valley. In 1886, a strong earthquake occurred in Charleston, South Carolina that had an estimated magnitude of 6.8 to 7.2. Much of the city was damaged or destroyed.

- Earthquake recovery takes years and interest often wanes. Recovery is particularly challenging in lower-middle-income countries and countries where multiple hazards and conflict combine to create a complex humanitarian emergency, such as Haiti. Recovery from a large earthquake can take years in wealthy countries too. In Japan, infrastructure has largely been rebuilt in areas hit hard by the 2011 earthquake and tsunami, but on the disaster’s 12th anniversary, around 30,000 people were still displaced and unable to return due to long-term radiation effects or health concerns. Donors may also experience fatigue given the overwhelming recovery needs, however, resources to support a full recovery as well as preparedness and risk reduction efforts are crucial.

How to Help

- Invest in safe building practices and reconstruction. Although local and national governments are responsible for building codes and ensuring they are enforced, philanthropy can support efforts to reduce vulnerability in the built environment through research, advocacy and supporting safe reconstruction.

- Support risk communication campaigns that are contextually and culturally appropriate. As disasters increase, communicating about reducing risk remains critically important. How the message is conveyed is just as important as what is communicated to ensure adoption. Following the 2015 Nepal earthquake, a weekly radio program and a connected drama helped shift social norms on earthquake-resilient home construction. Regular listeners were more likely to mention taking action than non-listeners.

- Learn from and apply traditional and indigenous ways of knowing. Observations about the environment passed down through generations have allowed communities to reduce disaster risk. The 2022 Global Assessment Report on Disaster Risk Reduction provided an example from New Zealand where, following the 2010–2011 and 2016 earthquakes in Canterbury, “the local Maori tribe Ngāi Tahu partnered with central and local governments in ensuring environmental restoration, biodiversity and future sustainability of the region.”

- Support the transfer knowledge from prepared communities to those at risk. Cities and countries that experience the most frequent smaller earthquakes often are extremely well-prepared while others that are due for a major earthquake may not be.

- Invest in resilient water infrastructure. Water and sanitation infrastructure are critical lifelines and provide vital services that help stop the spread of disease. Water supply disruptions following the 2011 Japan earthquake and tsunami had a ripple effect on public health. Lessons from Japan include retrofitting existing systems with seismic resilience upgrades and enhancing business continuity planning for sanitation systems. Both resilient small-scale water supplies—for rural areas—and large systems for urban centers are needed.

What Funders Are Doing

- Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) provided $750,000 to Hayata Destek Dernegi/Support to Life in 2023 to work with earthquake-affected communities in Turkey to implement 90 community-identified projects through the survivor and community-led approach.

- CDP provided $250,000 to the Haiti Development Institute through the Boston Foundation to help survivors from the 2021 earthquake in Haiti rebuild their lives by repairing homes and community infrastructure and restoring livelihoods.

- Open Society Foundations provided $2.5 million to Fondation Connaissance et Liberte (FOKAL) in 2021 to support smallholder farmers and micro-agribusinesses in Haiti who play a vital role in the local food supply chain and were affected by the August 2021 earthquake.

- W.K. Kellogg Foundation provided $30,000 to Partners in Health in 2020 to improve access to quality family care in northern Haiti following the October 2018 earthquake through reconstruction, procurement of medical supplies and coordination with local authorities.

- American Jewish World Service, Inc. provided $8,786 to Sulteng Bergerak in 2020 to work with communities affected by the earthquake and tsunami that struck the island of Sulawesi, Indonesia in September 2018 to advocate for their rights and ensure support for home reconstruction and rebuilding of livelihoods.

Learn More

- USGS Earthquakes

- USGS Earthquakes Map

- USGS The Science of Earthquakes

- USGS Cool Earthquake Facts

- Ready.gov – Earthquakes

- World Health Organization – Earthquakes

- Preparedness Made a Difference in Japan

- Great Shakeout Drills

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.