Disaster Philanthropy Playbook

Mental Health, Grief and Bereavement

Introduction

Updated May 2021

Following a disaster, communities are often faced with mental health crises. The loss of homes and belongings, the death of loved ones and pets, the destruction of community supports and displacement of friends and family can lead to enhanced emotional distress, anxiety, depression, suicidal tendencies and grief. The stress of living through a crisis and its aftermath exacerbates prior vulnerabilities and creates new ones. We know this to be true in almost every aspect of disaster and humanitarian crises, whether the underlying inequity is a condition of substandard housing, food insecurity, access to general health care or proximity to a hazard.

The intersection of mental health and disasters is one of the more culturally sensitive aspects of response and recovery work and one of the least funded among philanthropic disaster investments.

Several factors affect a community’s capacity to respond appropriately and effectively to the trauma and grief that accompany disasters and crises. Survivors are often diverse and have equally varied individual and communal approaches to mental health assessment and interventions. Needs are different for a single, traumatic event versus repeated disasters where environmental, ecological and financial vulnerabilities are present. Access to medical care, insurance that adequately covers mental health care and the social determinants of health (e.g., food, emotional and spiritual support, financial stability) influence preparedness for the impact of disasters.

The development process of the toolkit included stakeholder interviews, a convening and extensive research. The goal of the toolkit and the accompanying tip sheet and resources are to support philanthropic knowledge and encourage giving in the areas of mental health, grief and bereavement as it pertains to disasters. As with all CDP educational materials that are ever-expanding and evolving, this toolkit will be updated as more information becomes available. If you have questions or resources that you think would be useful, please send them to playbook@disasterphilanthropy.org.

This toolkit will help funders understand the disaster implications of mental health, grief and bereavement and the roles of donors, government and nongovernmental organizations. It identifies the variety of ways that donors can help and provides examples of grants that can be a source of inspiration. It also includes a significant resource section.

Definitions

Mental Health

According to mentalhealth.gov, “mental health includes our emotional, psychological, and social well-being. It affects how we think, feel, and act. It also helps determine how we handle stress, relate to others, and make choices. Mental health is important at every stage of life, from childhood and adolescence through adulthood.”

Grief

Grief is most often defined as a “person’s emotional response to the experience of loss.” But it can manifest itself with philosophical, physical, social, spiritual, behavioral and/or cognitive dimensions as well. While most people think about grief in the context of loss of a person or pet to death, in the context of disasters it can include loss of belongings, home, community, security and displacement of people.

Bereavement

While often used interchangeably with grief, bereavement is the mourning and grief that accompany the death of someone to whom there is a significant emotional attachment. For children, this is typically the passing of a parent, a parental figure or a sibling.

New York Life Foundation

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) was hired by the New York Life Foundation to carry out research on grief, bereavement and mental health in the context of disasters. Their description states, “Inspired by New York Life’s tradition of service and humanity, the New York Life Foundation has, since its founding in 1979, provided $300 million in charitable contributions to national and local nonprofit organizations. The Foundation invests in programs that benefit young people, particularly in the areas of educational enhancement and childhood bereavement support. The Foundation also facilitates “people power,” encouraging the community involvement of employees and agents of New York Life who volunteer where and when it matters most. … We are a leading resource for helping educators, families, communities and caregivers learn how to support children who have lost a parent or sibling. This focus aligns with our purpose, and who we are as a company.”

Disaster Context

The impact of a disaster is not over once a disaster has passed and/or an individual has an opportunity to reflect and adjust. A disaster can be seen as a “trauma with a capital T,” to distinguish it from smaller-scale traumatic events one may encounter in life such as life or job changes, relationship breakdowns or financial stress. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) states that trauma “has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s functioning and mental, physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being.’”

“Two years later [after the flood], residents were finally beginning to express the trauma they had undergone and their needs for mental health services.”

~ Karla Twedt-Ball, Senior Vice President, Programs and Community Investment, Greater Cedar Rapids Community Foundation

We know from the descriptions of researchers such as David Abramson at New York University, that people and communities who have experienced a weather-related disaster event go through a series of reactions to the event over the long arc of recovery. These reactions may be more or less complicated due to pre-existing physical and mental health conditions; social networks that bring attention and security; political power that gives communities a seat at the table for determining their own recovery; economic capital such as income, stable housing and insurance; and access to mental and behavioral diagnostic and treatment care.

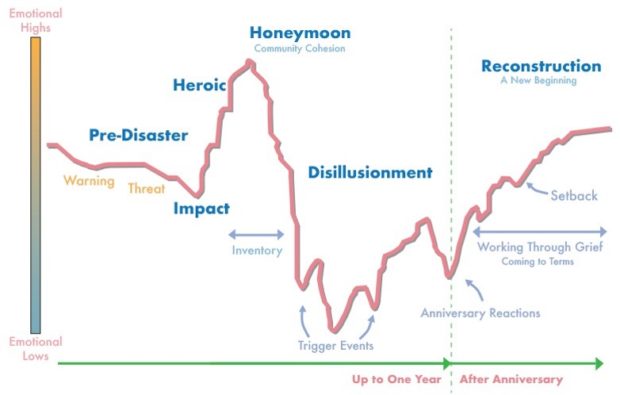

Disaster-related trauma is similar to other types of serious emergencies, especially those that result in death or profound personal loss. As the image above shows, the emotional highs and lows continue long after the disaster event itself. Many of the trigger events that cause serious mental health issues or depression often occur a year or more later.

People are usually caught up in preparation for a disaster that comes with a warning, such as a hurricane. If they have been through a past disaster, they are likely to experience flashbacks or anxiety. But in the immediate aftermath, stories of heroism and the sheer act of survival usually help stabilize and, in many cases even elevate, their mood. But as they take inventory of their losses and encounter difficulties to rebuild or regain normalcy, disillusionment sets in. They struggle, especially as the anniversary gets closer. Eventually, as their lives gain some stability, they will begin to work through their grief. Although setbacks occur, the intensity and frequency of these periods decrease, as indicated in the image above.

Yet, we also know that mental health responders or other professionals don’t typically identify many survivors who need care for various reasons. Survivors also don’t usually present themselves for assessment until long after the precipitating event, the media attention and the financial support have gone.

Pre-existing conditions, cultural awareness and understanding of mental health, access to health and mental health services, and the extent of the disaster are also factors that come into play in understanding the impact of a disaster on someone. Since each person has a unique starting point and different social and community safety nets, the same disaster will affect each person differently. For someone who was already dealing with mental health issues, a disaster may be the final straw that puts them over the edge and makes it impossible for them to cope with their current circumstances.

During CDP’s COVID-19: Support for Mental Health, Bereavement and Griefwebinar, Lisa Furst, vice president for policy, advocacy and education at Vibrant, said: “Funders are often focused on meeting the immediate needs that occur in the recovery phase. … However, I think there is a real opportunity for funders to focus their efforts into longer-term recovery phases following disasters because that is when mental health issues often emerge for people. Either because they stabilized enough materially to be able to address a mental health need, or because other short-term mental health and other supports have been withdrawn.”

With the vast footprint of the COVID-19 pandemic, we entered into new territory in assessing risk, evaluating impact and supporting interventions in mental and behavioral health. The timeline of the pandemic is unknown and has stretched over many months and potentially years. And for the first time in modern history, people around the country and the world are facing a disaster simultaneously. The COVID-19 quarantines, shutdowns and fears of becoming ill have impacted almost everyone, even those without any previous experiences with mental illness or poor mental health. Domestic violence and abuse hotlines report increased online communication and are preparing for an influx of calls once quarantines are lifted. Suicide ideation is up, and mental health hotlines report a huge increase in call volume.

The large number of COVID-19 infections and deaths in the U.S. and around the world have brought global attention to the impact of disasters on mental health, grief and bereavement. Many have been touched by loss and know at least one individual who has been infected or died. The quarantines have meant estrangement from loved ones in their hour of greatest need, making death extraordinarily challenging for the dying individual and their family and friends. Extremely limited funerals have removed one of the key cornerstones of the grieving process: the ability to gather as a community to mourn and celebrate the life of an individual. This further increases the trauma individuals, families and communities are experiencing.

Underlying Issues

Not everyone is equally at risk during a disaster. Many people face disproportionate impacts and higher levels of systemic (e.g., social and economic) and physical vulnerabilities.

“…for the larger population the barriers to treatment remain persistent: homelessness, rural locations, isolation, concentrations of low-income households in urban areas, race, and predispositions to health crises such as diabetes and heart disease and food deserts. Disasters magnify these disparities.”

~ Dr. Teri Brister, National Director, Research and Quality Assurance, National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI)

There are a number of special populations who are at a higher risk than others post-disaster:

- Elderly.

- School-aged children.

- Individuals living with chronic illness.

- Individuals with visual, hearing, and/or mobility-impairments.

- Individuals living with depression or other forms of mental illness.

- Individuals with limited access to health care.

- Parents/caregivers, especially female heads of households (because they often put the needs of everyone else in the family above their own).

- Individuals living at or below the poverty line.

- Immigrant populations and undocumented individuals.

- First responders, emergency services, fire and police department personnel.

People responding to a disaster need to pay attention to pre-existing vulnerabilities to help direct their resources – human and financial – appropriately.

Signs of Concern

In the aftermath of a natural disaster or human-made tragedy, people with pre-disaster mental health issues are not the only ones who will need support. Many members of the general public will also need mental health services.

Depression and depressive-like symptoms are the most prevalent mental health issues post-disaster, with sleep problems being the most commonly reported. Communities that have experienced serious trauma or major disasters often see an increase in PTSD symptoms and community mental health challenges 12 to 18 months post-disaster. Depressive-like symptoms can also be tied to domestic violence, substance abuse and suicide; all of these tend to increase after a disaster.

However, according to SAMHSA, there are a number of risk factors or warning signs related to post-disaster stress and trauma. These are the same issues that are reported to affect bereaved people as well:

- Eating or sleeping too much or too little.

- Pulling away from people and things.

- Having low or no energy.

- Having unexplained aches and pains, such as constant stomachaches or headaches.

- Feeling helpless or hopeless.

- Excessive smoking, drinking, or using drugs, including prescription medications.

- Worrying a lot of the time; feeling guilty but not sure why.

- Thinking of hurting or killing yourself or someone else.

- Having difficulty readjusting to home or work life.

Additionally, the anniversary of the event or certain sights, sounds and experiences may trigger emotional distress. Those who have lived through major hurricanes for example, often find severe rainstorms and hurricane season generally to be stress-inducing.

People often minimize their personal mental health needs. They are typically in denial about their anxiety and stress levels, or want to help others instead. Many people – especially those from Black, Indigenous or People of Color (BIPOC) communities – do not ask for help due to the stigmatization of mental health challenges. This minimization of need is also particularly true for frontline workers and first responders who believe that they should be strong. It is vital that programs and services address the needs of all communities in their outreach and informational materials.

Trauma-Informed Care

Increasingly, in mental health circles, there is a focus on trauma-informed care. This kind of therapeutic intervention occurs when a program or organization recognizes the “widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for healing; recognizes the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and responds by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization.”

“More than anything, survivors need to have their despair normalized and need to have basic coping tips to move forward.”

~ Nancy Beers, Founding Director of the Midwest Early Recovery Fund, Center for Disaster Philanthropy

Trauma-informed services work to meet clients “where they are” rather than engaging in processes that could re-traumatize them. For NGOs and philanthropy, this could include extensive outreach and coordinated intake to avoid having disaster survivors retell their stories repeatedly.

Governmental and nongovernmental policies and planning to address disaster mental health must continue to draw from academic research, programmatic responses, and innovations in diagnostic and therapeutic care. Legislators, care providers and disaster funders should take the long view in supporting mental health issues. Organizations need to prepare for delays in expressions of distress and financial need since those who experience mental health challenges often do not seek care until long after the precipitating event.

Delivery of Services

Post-disaster, the need for mental health, bereavement and grief assessment and support is urgent and widespread. Governmental organizations and NGOs have developed extensive response mechanisms to support these mental health needs in areas struck by disasters. These resources are deployed to help victims and survivors, particularly those who have suffered the loss of a close family member or friend.

However, limited funds often constrain these services. This is where philanthropy has a significant role in ensuring that services are available as long as the need exists. Most government and nongovernmental services provide basic crisis counseling and care. In areas of more acute need – repetitive disasters, significant impact – it is essential that care be trauma-informed and long-term.

Role of Governmental Organizations

Domestically, only a few programs support mental health and even fewer after a disaster. Governmental organizations provide limited support for grief and bereavement after crises, with the exception of instances of large-scale violence – i.e., mass shootings. Internationally, this varies greatly depending upon the country. Some countries provide a great deal of crisis and mental health support, in others it is minimal to non-existent.

Through the use of an emergency operations center, governmental organizations coordinate the overall disaster response, including efforts related to mental health. This governmental coordination ensures that the right resources get to the right places at the right time. Only those organizations who have the capacity to deliver appropriate mental health, bereavement and grief services are provided access to the disaster area.

In some cases, governmental organizations are capable of providing or funding these services. In the United States, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Crisis Counseling Assistance and Training Program (CCP) fills this role. The program funds mental health assistance and training in areas that have received a major disaster declaration (meaning smaller disasters do not receive this support). Under the CCP, FEMA can fund an organization providing direct mental health assistance for the first 60 days, and up to an additional nine months after a disaster. It does this through two separate programs:

Immediate Services Program (ISP)

- Application is due 14 days after a Presidential major disaster declaration that includes Individual Assistance (IA).

- FEMA provides funds for up to 60 days of services immediately following the approval of IA for a disaster.

- FEMA awards and monitors the ISP federal award in coordination with SAMHSA.

Regular Services Program (RSP)

- The application is due 60 days after a Presidential major disaster declaration that includes IA.

- FEMA provides funds for up to nine months from the date of the notice of award.

- SAMHSA awards and monitors the RSP federal award in coordination with FEMA.

These are separate programs that require separate applications. ISP is not a prerequisite for RSP, nor is RSP required automatically when ISP has been approved.

Disaster crisis counseling is very different from ongoing mental health treatment. FEMA states, “Crisis counseling seeks to help survivors understand that they are experiencing common reactions to extraordinary occurrences. Crisis counselors treat each individual and group they encounter as if it were the only one, keep no formal individual records or case files. They also find opportunities to engage survivors, encouraging them to talk about their experiences and teaching ways to manage stress. Counselors help enhance social and emotional connections to others in the community and promote effective coping strategies and resilience. Crisis counselors work closely with community organizations to familiarize themselves with available resources so they can refer survivors to behavioral health treatment and other services.”

While this can be very useful for individuals who have suffered some impact or loss from the disaster, it is not as helpful for people whose loss was more extensive or who have been bereaved by the disaster. As the disaster moves further into the past, people still suffering are less likely to be able to access government supported services. This is where the role of NGOs becomes critical.

Role of Nongovernmental Organizations

Much of the work in community mental health is done by nongovernmental organizations; the same is true for grief and bereavement support. NGOs providing these support services can be incredibly varied, ranging from professional associations to faith-based organizations and even local community organizations. These organizations may provide support to a very focused group of people such as emergency responders, children or the elderly; or they may provide services to a wide cross-section of people. In many cases, NGOs will provide direct assistance, including counseling, psychological and psychiatric care at low- or no-cost to those who are experiencing mental health concerns, bereavement or grief after a disaster.

In general, NGOs should make their availability known, but should not actually respond to the area until their presence and services have been requested. Mental health, bereavement and grief support after a disaster must be carefully coordinated to ensure that everyone receives the help that they need. Organizations who respond without being requested run the risk of interfering by not properly connecting and coordinating with other organizations and local providers. Local coordination is essential to providing ongoing support after NGOs leave the disaster area since they will hand over the care of clients to local professionals.

National Voluntary Organizations Active in Disasters (NVOAD) has a number of members that specialize in providing “emotional and spiritual care” after a disaster. According to NVOAD’s guidelines, “Disaster spiritual care is a process through which individuals, families, and communities affected by disaster draw upon their rich heritage of faith, hope, community, and meaning as a form of strength that bolsters the recovery process.” NVOAD’s emotional and spiritual care committee also has a resource guide called “Light Our Way” available in English and Spanish to provide advice and information for those looking to get involved in this area.

Role of Philanthropy

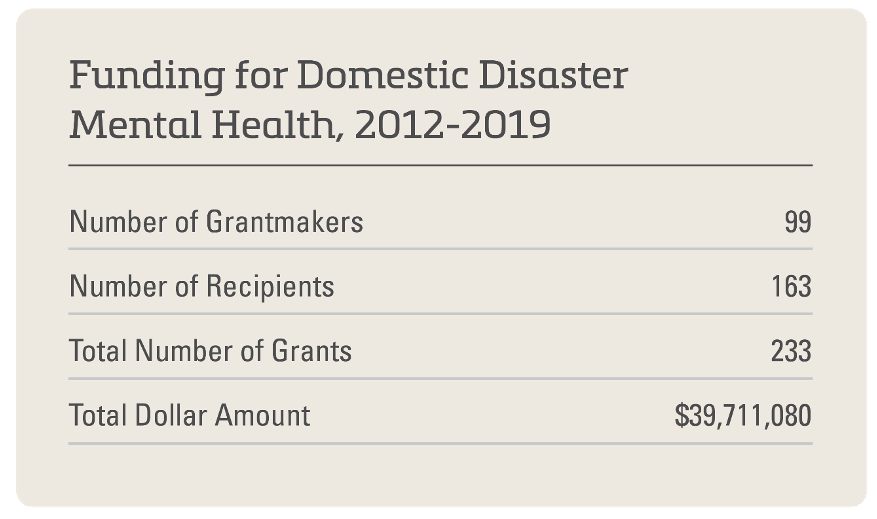

We know that mental health does not receive a large share of the funding support for disaster recovery. With our partners at Candid, we’ve been able to track philanthropic grants from 2012-2019 for mental health services following a disaster. When you consider that this covers seven years during which we saw Superstorm Sandy, the Ebola Crisis and a series of major hurricanes, the numbers look small, particularly in comparison to other facets of recovery. These numbers would be even smaller when looking at grief and bereavement as separate components.

As shown in the “What Donors Are Doing” section, there are many ideas for how philanthropy can provide mental health, grief and bereavement support after a disaster. An essential role for funders is ensuring that funds are available for complex care over extended periods. Funding for these services throughout the entire disaster recovery period is critical. Once government funding runs out – usually within less than a year – philanthropy provides the only formalized funding mechanism for mental health services, outside of what insurance provides. This funding should include the delivery of counseling services, awareness and educational campaigns that are mainstream, culturally and racially diverse across traditional communications and social media platforms that advertise the availability of services and the importance of accessing mental health support.

Improving Mental Health, Grief and Bereavement Supports

Recommendations for Blue Sky Times

There are a number of actions that governments, nongovernmental organizations and philanthropy can take ahead of a disaster (in “blue skies”), during and after a disaster. These activities can enhance individual and community responses to mental health, grief and bereavement challenges after a disaster. As this toolkit and the Playbook are aimed at donors and philanthropy, we encourage to fund the development of programs and supports recommended in the NGO section. Beyond providing direct funds, we also ask you to consider playing an advocacy role by informing and urging governments to expand their efforts.

Government

- Have a big and welcoming “table.” Your community’s recovery is only as strong and good as the recovery of its least privileged member. Make sure the right voices are involved in decision-making and long-term planning so that mental health, among many other pressing issues, is represented by forceful and knowledgeable community leaders. This planning should be carried out long before a disaster strikes.

- Determine which indicators suggest gaps in support within the mental health “system” in your community. This could include low numbers of inpatient treatment beds, high incidence of substance abuse and addiction, health insurance deserts or inadequate coverage for mental health support, weak non-profit mental health infrastructure, or overall access issues. Work to address those that are within your purview.

- Foster collaborative, comprehensive approaches to pre- and post-disaster preparedness and response. Support training and disaster preparedness for healthcare nonprofits, social service agencies, schools and faith-based organizations. During CDP’s webinar on supporting mental health, bereavement and grief, Heather Nesle, president of the New York Life Foundation, reported that 93% of educators surveyed by the American Teacher’s Federation identified needing and wanting training to help grieving students.

- Convene community gatherings that foster social cohesion, reduce isolation and recognize the shared experiences of community members both pre- and post-disaster. The stronger a community is ahead of a disaster, the stronger it is likely to be after a disaster.

- Check the laws and make changes where needed. Often state health departments have laws that restrict or prevent addressing mental health needs in a timely fashion. For instance, can persons who have prescriptions get vacation overrides and receive additional refills of their medications leading up to a disaster or immediately following when they may be in transition to shelter or temporary housing? Do differing counties or municipalities or the state have specific laws that allow for licensed professionals to receive temporary licensing to practice in your locality in the case of a disaster, allowing volunteers from out-of-state to assist?

Nongovernmental Organizations

- Examine cultural barriers to voicing mental health needs. Identify the respected influencers in the community who can be marshalled to de-stigmatize or lessen discrimination about mental health (e.g., teachers, coaches, religious leaders, elected officials). Ensure that materials and services represent the cultural diversity of the community (languages, pictures, staffing, etc.)

- Promote honesty about mental health needs and advocacy for support through public storytelling. Work with the media to raise the awareness of the prevalence of PTSD in the aftermath of a disaster via local television, radio and internet. Educate the general public on the signs of depression (i.e., difficulty sleeping) and direct people to where they can get help.

- Build capacity. Adding disaster response to your current mission and programmatic activities should incorporate the needs of your staff and their self-care, as well as spotting and addressing the mental health needs of your current clients. During CDP’s COVID-19 webinar on support for mental health, bereavement and grief, Lisa Furst said that the National Disaster Helpline’s call volume spiked in March and April before stabilizing at levels that have remained higher than pre-COVID numbers.

- Develop a flexible and trusted referral network. Your organization does not need to be or do EVERYTHING. If mental health services are your gig, wonderful! You will be a vital player in the recovery of individuals, families and communities. If not, know who is good at it and has the capacity to provide sensitive, supportive care. Identify someone in that organization as your referral point of contact.

Philanthropy

- Be ready to support organizations after a disaster occurs. This could include building relationships ahead of time, cataloging the variety of venues and vehicles that can be used to reach out to individuals and communities in need of mental health support, and/or creating MOUs with emergency response organizations so they can provide immediate psychological first aid and crisis counseling.

- Support research, analysis and education on health issues and mental health concerns post-disaster. Examine the successes and lessons learned from one disaster to become better prepared for the next disaster. Ensure that a comprehensive information dissemination plan is a key component of any funded research.

- Fund crisis support counselors in non-traditional settings. Many NGOs would like funding to host crisis counselors in schools, community centers and faith-based organizations to reach people who are not seeking out mental health assistance. This can help reduce stigma and make it easier for people in need to reach out post-disaster.

- Be on the lookout for populations that may have high need but little attention or response infrastructure. Think about how you as a funder can build the capacity of organizations and communities so they’re ready to respond when a disaster hits.

- Be a good and patient listener. This is critical to identifying stresses and strains on your grantees, your fellow funders and your community. Sometimes advice, a listening ear or technical assistance is as valuable as the funds.

- Think local. Work with organizations that have the trust of and can reach out to marginalized and underrepresented communities. While national and international NGOs do great work and need funding, also support the existing community networks.

“Location is everything, whether the services are being delivered in brick-and-mortar buildings or in mobile clinics. Going to schools with high registrations and communities with high need in general, church parking lots, school parking lots, community centers—making therapy available and accessible was a key to impact.”

~ Sally Ray, Director of Strategic Initiatives, Center for Disaster Philanthropy

Recommendations for Times of Disaster

After a disaster, there are many issues and concerns fighting for attention. It is important, however, that support for mental health generally, and grief and bereavement specifically, be addressed.

Government

- Keep that table wide. After a disaster, make sure to include issues related to mental health and mental health services in your community needs assessments as you determine the next steps to move forward in response and recovery.

- Be an advocate for your residents. Make sure that mental health needs are part of the case that you make for disaster funding or changes in policies or laws. If you receive a disaster case management grant, encourage those implementing the grant to be sensitive to mental health issues alongside housing, personal property, transportation and other needs.

Nongovernmental Organizations

- Keep track of inquiries and provision of services. Be sure to track simple, easily acquired data to tell the story of who is requesting services and who is receiving services. This will become the basis for fund requests and reporting.

- Offer long-term psychological counseling and case management to disaster survivors. Once FEMA funding expires, there is still going to be intense need within the community. Focus your resources on the one-year-plus needs to support disaster recovery.

Philanthropy

- Be flexible. Adjust your deadlines, applications, reporting procedures and expectations to take into account that mental and behavioral health symptoms may take a long time to appear and even longer to address. Fund in the response and recovery phases of a disaster.

- Be ready for the long haul. Many post-disaster mental health issues present themselves at around the 18-month mark following the disaster event. This is also the time that most grant funding ends. Keep reserves in hand to address the delayed uptick in presentation of mental health problems.

“Funders are often focused on meeting the immediate needs that occur in the recovery phase. However, I think there is a real opportunity for funders to focus their efforts into longer-term recovery phases following disasters because that is when mental health issues often emerge for people. Either because they stabilized enough materially to be able to address a mental health need or because other short-term mental health and other supports have been withdrawn.”

~Lisa Furst, Vice President for Policy, Advocacy and Education at Vibrant

- Be ready for complexity. There is seldom one problem to address. There may be multiple layers of psychic injury that are compounded by disaster: past abuse, current or prior history of substance mismanagement or addiction, co-occurring disorders, low levels of financial/insurance/relationship support, etc. Attacking only one problem may be insufficient to provide for long-term positive impact.

- Reward innovation. Support programs that have robust and imaginative outreach to individuals and communities in need. This may require translation services, presence in disaster and other sheltering programs, and mobile clinics.

- Partner. Consider institutional partners — schools, religious organizations, community clinics — who can add mental health assistance or expand current mental health services. Inquire about the provision of mental health services when you are evaluating disaster response organizations for funding.

- Co-fund. Some communities will have a “big lift” to address mental health needs. If your gift can be magnified and leveraged in collaboration with other funders, consider this an opportunity to help your community build mental health resiliency for facing the next disaster.

What Donors are Doing

There have been some very interesting and innovative grants offered by funders to support communities. Here are a few examples of disaster and non-disaster related mental health, grief and bereavement grants:

Center for Disaster Philanthropy

- The Center for Disaster Philanthropy through its COVID-19 Response Fund has provided several grants linked to mental health and disasters. These include:

- A $250,000 grant in 2020 to the National Alliance on Mental Illness to expand their work on mental health support related to COVID and other disasters. NAMI’s plan includes: 1) ensuring access to timely, practical mental health information, 2) bolstering the capacity of NAMI’s Helpline and 3) fortifying their network of NAMI affiliates and NAMI State Organizations.

- A $500,000 grant in 2020 to Action Aid/Feminist Humanitarian Network (FHN) for their response to the COVID-19 pandemic in several countries including Liberia, Bangladesh, Colombia, Zimbabwe and Somaliland. Fiscally sponsored by ActionAid, the FHN is supporting the members of local women’s rights organizations through localized, women-led COVID-19 responses including psychosocial support via helplines and counseling.

- Catholic Charities USA (CCUSA) received $500,000 in 2020 to assist those most acutely affected by COVID-19 throughout local communities in the U.S. Focus is on serving the most vulnerable, especially the elderly, unemployed and children and youth. CCUSA will provide holistic case management to ensure clients are connected with the resources and support they require immediately and for the long-term.

- In 2020, Vibrant Emotional Health received $500,000 to support its Crisis Emotional Care Team in its response to the COVID-19 pandemic over a period of 18 months. In recognition of the pandemic’s national scope, its associated prolonged stresses and the increased incidence of clinically significant mental health challenges in the wake of this disaster, Vibrant will: 1) develop a cadre of volunteer mental health professionals active across all 50 states and the U.S. territories to provide services to support the resilience of communities and organizations during and after the pandemic and 2) provide state-of-the-art disaster mental health training to licensed mental health professionals on an ongoing and “just in time” basis.

- Through its Global Recovery Fund, CDP provided two grants in 2020 to support mental health and bereavement including:

- A $200,000 grant to support Doctors without Borders (MSF) work in Venezuela including providing provide mental health outreach and services to victims of violence in urban slums.

- The Australian Red Cross Society was awarded $336,000 for bushfire support including bereavement payments to next of kin for people who died in the fires.

- CDP Hurricane Harvey Recovery Fund provided:

- A $163,670 grant in 2018 to Mental Health America of Greater Houston (MHAGH) to complete the funding to establish the Dickinson Mental Health Project, a collaborative effort with the Hackett Centre at the Meadows Mental Health Policy Institute, DePelchin Children’s Centre, Texas Children’s Hospital (a CDP Harvey Fund grantee), Collaborative for Children and other local partners. Dickinson, Texas, saw significant damage from Hurricane Harvey. The trauma and grief it created for the children, youth, teachers, staff and parents within the school district continues to affect the entire community.

- The Texas Children’s Hospital was awarded $779,917, to be spent over two years, for the expansion of the Trauma and Grief Center at Texas Children’s Hospital’s Mobile Unit program to increase access to best-practice care among traumatized and bereaved children affected by Hurricane Harvey.

New York Life Foundation

- The New York Life Foundation provides extensive support for mental health, bereavement and grief support to disaster victims and survivors.

- Ongoing support of $1.25 million to fund the National Alliance for Grieving Children’s Grief Reach program to support childhood bereavement efforts.

- In 2019, some of the grants New York Life provided included:

- $1.2 million to support the Alliance for Young Artists and Writers’ Scholastic Art and Writing Awards for young people who submit artwork exploring their experiences with the death of a close loved one; online exhibitions of the winning works; and summer workshops. Six students will be selected for the New York Life Award, which includes a $1,000 scholarship.

- $3 million to the Boys and Girls Clubs of America to support their “Be There” program, which helps club members cope with loss, death and grief by fostering a culture of wellness across all clubs. It will also enable BGCA to build the Ready, Set, Action program, a strength-based curriculum developed by the PEAR Institute: Partnerships in Education and Resiliency, which builds club members’ competence and resilience.

- $450,000 to Outward Bound to support the Outward Bound for Grieving Teens program. This program combines the traditional Outward Bound immersive wilderness experience with grief processing activities to help bereaved teens move forward.

- $500,000 to support StoryCorps to develop new content, tools and training resources to help bereavement service providers use the power of stories to help children cope with the death of a parent, sibling or loved one.

Other Funders and Donors

- In 2019, the John Ben Snow Memorial Trust supported the work of the Trauma Intervention Program of Northern Nevada with a $5,000 grant to train volunteers to provide mental health and trauma intervention after disasters and emergencies.

- Johnson & Johnson’s Corporate Giving program invested $5 million through a grant to Save the Children which was used to partially support a new program dedicated to mental health and psychosocial support for children in the United States and around the world.

- In 2020, the Funeral Service Foundation supported the work of Cornerstone of Hope with an undetermined amount to develop a curriculum for bereavement training for first responders. The foundation also supported KinderMourn to provide grief and other services to low-income youth via their “Helping the Hurt” program.

- The Johnny Mac Soldiers Fund, Lockheed Martin and Rosie’s Gives Back support the Tragedy Assistance Program for Survivors (TAPS) “College Experience” Program to help bereaved children of fallen military members navigate the transition to post-secondary school. The New York Life Foundation has also provided significant support to TAPS through over $500,000 in donations.

- The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration and the Louisiana Children’s Trust Fund have partnered to provide ongoing support to Project Fleur-de-lis as part of the National Child Traumatic Stress Network. Project Fleur-de-lis provides school-based trauma-focused intervention services, military family interventions, school-based suicide risk assessment support, and restorative approaches training and implementation support.

- Through the Child Trauma Research Program at the University of California, the National Child Traumatic Stress Network received an unspecified grant in 2020 from the Irving Harris Foundation to create and publish “Fighting the Big Virus: Trinka, Sam, and Littletown Work Together.” The story and companion booklet were developed to help young children and their families begin to talk about their experiences and feelings related to the global coronavirus pandemic.

- The Irene W. and C.B. Pennington Foundation awarded the Baton Rouge Children’s Advocacy Center a $30,000 grant after the floods in Louisiana in 2016. The Center provides licensed therapists to youth and families exposed to trauma. Using scientifically-based approaches, therapists tap into the resilience of children so that they can shift the life experience of trauma from potential tragedy to growth and success.

Key Takeaways

- Mental health, grief and bereavement are underfunded, and yet, are some of the most critically needed services for full and healthy recovery.

- Philanthropy can have a tremendous, long-term impact. It is the only formalized funding mechanism for mental health services after federal disaster funding of behavioral health programs close. FEMA’s Crisis Counseling Program is a short-term program (approximately 3 months to one-year post-disaster). In non-FEMA declared disasters, philanthropy is the sole funding mechanism.

- Long-term funding for mental health services and counseling programs is vitally important for the recovery of the affected individuals and the community as a whole.

- Education and awareness campaigns can help encourage individuals to take advantage of counseling programs.

- Media messaging that is appropriate and tailored to specific populations is extremely important. The more people know about available counseling programs, the more people will seek help.

Resources

The following resources are free and available to the general public using the links found in the tables. The focus of many of these resources is children and youth, as they both tend to be among the most vulnerable in a disaster and also drivers of community well-being and recovery. As David Abramson, Yoon Soo Park, Tasha Stahling-Ariza and Irwin Redlener expressed in their study following Hurricane Katrina, “Children’s mental health recovery in a post-disaster setting can serve as a bellwether indicator of successful recovery or as a lagging indicator of system dysfunction and failed recovery.”[1]

When the resource is targeted to a general audience or to other specific populations, this is reflected in the heading and in the title. There are many populations who are deserving of mental health funding that do not appear in this collection. For example, there are multiple scientific studies about the impacts of disaster exposure on first responders, but not much on the topic is published that can be easily accessed by a general audience. We will update the listing as we discover new resources or they are brought to our attention.

We encourage funders to examine available resources prior to investing in development of new resources to support mental health responses to avoid duplication and identify gaps in the literature that might contribute to a sensitive approach to preparedness and recovery for all affected by disasters.

Resources for Childcare Providers

Resources for Parents and Caregivers

Resources for Teachers

Resources for a General Audience

Resources for Children

Resources for Youth and Young Adults

Resources for Mental Health Providers

Apps

Foundational Research

[1] David M. Abramson, Yoon Soo Park, Tasha Stehling-Ariza and Irwin Redlener, “Children as Bellwethers of Recovery: Dysfunctional Systems and the Effects of Parents, Households, and Neighborhoods on Serious Emotional Disturbance in Children After Hurricane Katrina,” Cambridge University Press, April 8, 2013, cambridge.org.