Last updated:

U.S. Civil Unrest

Overview

The homicide of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, led to months of protests to address racism at all levels of society. Floyd died during an arrest after Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin kneeled on his neck for 8 minutes, 46 seconds.

On April 20, 2021, Officer Chauvin was found guilty of murder in the second degree while committing a felony, third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. While Chauvin could face up to 40 years for the first conviction, up to 25 for the second and up to 10 years for the last charge, his sentences may be lower due to his lack of prior criminal history. According to CNN, “Minnesota’s sentencing guidelines recommend about 12.5 years in prison for each murder charge and about four years for the manslaughter charge.” On June 25, Chauvin received a 22.5-year sentence. Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison called it, “one of the longest prison terms ever issued to a former police officer for the unlawful use of deadly force.”

Saying that this sentence was a “moment of real accountability,” Ellison also pushed for the passage of the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, which passed the House in March. The act is a reform bill aimed at banning chokeholds and limiting no-knock warrants. It would also prohibit racial or religious profiling and require data collection on police encounters. The act would also impact qualified immunity for police officers. States and cities across the country have implemented police reform bills or acts to enable similar changes.

On June 24, 2021, there was a preliminary, bipartisan agreement on a modified version of the bill passed by the House. Led by Senators Tim Scott, R-S.C., and Cory Booker, D-N.J., and Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., the sticking point was reportedly qualified immunity for police officers. President Biden had asked for the bill to be approved by the one-year anniversary of Floyd’s murder but agreement could not be reached by the deadline.

Additional legislative campaigns have included the Breathe Act which is a campaign from the Movement for Black Lives’ Electoral Justice Project. It is much more restrictive than the Justice in Policing bill. According to Vox it, “calls for the closure of federal agencies like Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), and divesting federal funds allocated to law enforcement. It also includes an array of other reforms including offering federal grants to local governments to invest in public safety alternatives, and pushing for an end to mandatory minimums.”

Three other officers also participated in Floyd’s arrest. All four officers were fired the day after the murder. The other police officers were charged on June 3, 2020 with aiding and abetting both second-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter. Their trial has been pushed back to March 2022.

As with numerous other police-involved deaths, peaceful protests for racial justice took place to call attention to this ongoing concern. Black Lives Matter and other activists behind the protests issued numerous complaints against police for racial discrimination and brutality in policing communities of color. They have also demanded investment in Black, Indigenous and People of Color (BIPOC) communities and disinvestment in police services.

Between May 25 and Nov. 18, 2020, protests occurred in more than 4,446 cities worldwide, including in all states, territories and Washington, D.C., and internationally in more than 60 countries. While most of the protests were peaceful, minor looting, broken windows and arson were common. Although most of the global protests were linked to the racial injustice issues raised in the U.S., they also provided an opportunity for communities to raise their own issues and concerns.

Many of the protests in the U.S. ended with police shooting tear gas, pepper spray and rubber or wooden bullets at protestors, including many who were protesting peacefully. More public attention has been focused on exposing racially motivated police activities and stories of white people harassing people of color in public spaces.

Throughout summer and fall 2020, there were also protests and rallies connected to the COVID-19 pandemic and the 2020 Presidential Election. These have an in-direct but important connection to the racial protests because they were carried out in part by groups associated with white supremacy organizations or people who have been outspoken about Black Lives Matter.

Between March and October 2020, there were major protests in 26 countries against the COVID-19 lockdown restrictions. Several of these have occurred across the U.S., including armed protests in Michigan in May 2020. While research has shown that racial justice protests did not lead to increased COVID-19 cases, several of the rallies for then-President Donald Trump were determined to be super spreader events, including 30,000 cases and 700 deaths stemming from 18 rallies. The anti-mask/anti-COVID-19 restriction protests have continued as cases ebb and flow in different communities and countries.

As of September 2021, there are continued protests about COVID-19 as it pertains to vaccine mandates, including by health care professionals and first responders. Approximately 27% of health care practitioners were not vaccinated as of July 2021. There isn’t a national standard for tracking first responders, but as of August 2021, 54% of Los Angeles Policedepartment staff are vaccinated and just 47% of New York police officers. This is despite COVID-19 being the leading cause of death for law enforcement in 2021; 71 of 155 line-of-duty deaths by June 30, 2021 were due to the virus.

In Melbourne, Australia, the government halted construction due to protests occurring against vaccine mandates in the construction industry. At least 13% of the cases of COVID-19 in Victoria state are linked to construction sites (which led to the vaccine mandate).

The national movement of racial reckoning has also led to more interest in studying racism, as well as protests against schools including “critical race theory” in their curricula. “Critical Race Theory (CRT) is a framework that offers researchers, practitioners, and policy-makers a race-conscious approach to understanding educational inequality and structural racism to find solutions that lead to greater justice. Placing race at the center of analysis, Critical Race Theory scholars interrogate policies and practices that are taken for granted to uncover the overt and covert ways that racist ideologies, structures, and institutions create and maintain racial inequality.”

Key facts

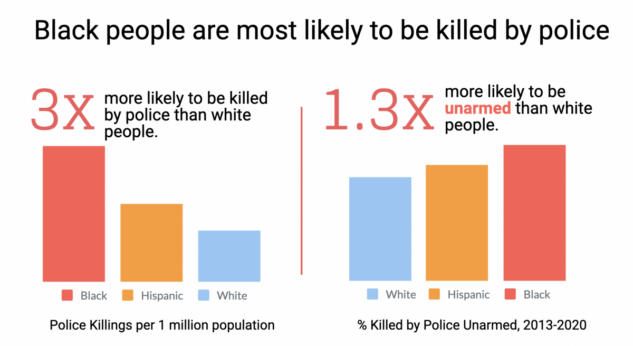

Being killed by police is a leading cause of death in the US for Black men and boys; about 1 in 1,000 will die this way. They are 2.5-3 times more likely to die than white men and boys at the hands of police. Black people are 1.3 times more likely to be unarmed during their death from police than white people. Other people of color, including Latino men and boys, Black women and girls, and Native American men, women and children, also experience higher rates of death due to police violence than their white counterparts.

Throughout Derek Chauvin’s trial, March 29 through April 17, 2021, an average of three people a day – or 64 people in total – died at the hands of police. Over half of this number is made up of Black and Latinx individuals. In 2021, there have been 740 killings by police recorded by Mapping Police Violence as of Sept. 7, 2021. From Jan. 1 to Sept. 7, 2021, there have only been 10 days without killings by police. So far this year, police killings are in line with the rates in past years.

In 2020, 1,127 people were killed by police. Black people made up 28% of this group, despite only making up 13% of the country’s population. There were only 18 days in 2020 when the police did not kill someone, with only Rhode Island and Vermont reporting zero police killings.

A report from researchers at Yale and the University of Pennsylvania published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health states: “Over the past five years there has been no reduction in the racial disparity in fatal police shooting victims despite increased use of body cameras and closer media scrutiny … Using information from a national database compiled and maintained by The Washington Post, researchers found that victims identifying as Black, Indigenous, or People of Color (BIPOC), whether armed or unarmed, had significantly higher death rates compared with whites. And those numbers remained relatively unchanged from 2015 to May 2020.”

Research from the Mapping Police Violence has found that between 1993 and 2000:

- “Police killed Black people at higher rates than white people in 47 of the 50 largest US cities.” All people killed in Miami were Black and brown people. In Chicago, the killing of Black individuals was 22 times higher than white individuals.

- “Police violence is changing over time.” Researchers found that police killings have increased in suburban and rural areas but decreased in urban centers.

- “Most killings by police begin with traffic stops, mental health checks, domestic disturbances, or reported low-level offenses.” Traffic stops led to a killing 120 times in 2020.

- “Levels of violent crime in US cities do not determine rates of police violence.” In a review of data, there is no correlation between cities with high crime rates and police killings.

- “98.3% of killings by police from 2013-2020 have not resulted in officers being charged with a crime.” Derek Chauvin’s conviction was lauded by activists because it was so rare, even for a videotaped crime.

Calls for racial justice

While the response to the racial justice protests from the Trump administration was very negative, President Biden’s inaugural speech and the first few Executive Orders were promising. In his speech, he promised to deliver racial justice and said: “A cry for racial justice some 400 years in the making moves us. The dream of justice for all will be deferred no longer. … And now, a rise in political extremism, white supremacy, domestic terrorism that we must confront and we will defeat.”

The calls for racial justice and the end of police brutality resonated broadly with people across the country beyond the Black community. Protests had a racially diverse attendance and occurred in non-BIPOC communities. While companies and organizations have responded by making donations or releasing statements in support of racial equality, it is critical that those actions are reflected in updated hiring practices, more diverse staff and board leadership, improved pay scales, and equal treatment of employees of color.

There are several campaigns being organized around “defunding the police,” “abolishing the police” and/or “police reform.”

- Police reform refers to making changes to the ways in which police and communities interact, especially during arrests. This includes limiting the use of force, demilitarization of police, training and the requirement for police to wear/use body cams.

- Defunding the police is similar to reform but suggests moving resources currently in the police budget to human services and community organizations. For example, instead of police responding to a call of someone drunk in public they would be seen by outreach and harm reduction workers experienced in addictions. Instead of a “drunk tank,” they could be taken to a rehab facility, or if they have a home, driven safely home.

- Abolishing the police is a call to remove police altogether, beginning with a significant reduction in staffing and then eventually removing the police force completely.

Related reading

There are both immediate and long-term needs in support the current crisis of civil unrest in the country.

Immediate needs during protests

When protests occur, immediate needs include support for the safety and well-being of protestors and their families, including bail bonds, first aid and medical support, financial assistance for families of those arrested, and support for safe spaces where protestors can receive medical treatment, access healing modalities or mutual aid, or take a break from the sun, crowds or tear gas.

Long-term needs

On a longer-term basis, look to this Nonprofit Quarterly article by author Will Cordery. He challenges philanthropy: “My call to philanthropy: fund racial justice. Fund the hell out of it. Fund racial justice work that centers organizing and power-building to counter anti-Blackness. Fund racial justice work that centers the lived experiences, leadership, and communities of Black people. Fund spaces that foster a radical imagination and the creation of new ways of being that could potentially replace centuries of systemic and structural racist practices in our society. And have the staying power to give Black activists and allies the space to develop effective organizing strategies to achieve lasting change.”

In her letter after Derek Chauvin’s conviction, TFN’s Pat Smith called out several responses to the uprisings that need support.

“There has already been great work being done at the grassroots level, in Minneapolis and beyond. We encourage you and your grantmaking organizations to increase support of frontline organizations led by BIPOC members of our communities through general operating grants, and to truly partner with these groups as equals at the decision-making tables in the communities you serve.”

Contact CDP

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working in this crisis to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

Donor recommendations

If you are a donor looking for recommendations on how to help in this crisis, please email Regine A. Webster.

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

More ways to help

ABFE, A Philanthropic Partnership for Black Communities, issued a list of imperatives for philanthropy, initially for responding to COVID-19 but applicable and expanded to include the emerging response to Floyd’s murder. Several philanthropic-serving organizations have asked that philanthropy support ABFE’s call and recommendations. Though we summarized the imperatives below, we encourage you to read the full document.

- Build Agency. Increase investments in Black-led organizations that connect individuals and families to a wide array of resources and build power in our communities to lead substantive change.

- Push Structural Change. Given deep-seated inequities, COVID-19 relief and police reform efforts must take a “long view” and consider policy and system reform needed to improve conditions in Black communities beyond federal and philanthropic emergency and response efforts.

- Encourage Shared Responsibility. Philanthropic funds, particularly those under the leadership of Black foundation executives are part of the solution. However, the targeted investment of all philanthropies as well as public dollars are needed to transform conditions in Black communities in both relief and long-term efforts.

- Use Endowments. The health-driven economic recession has negatively impacted foundation endowments. Therefore, there is increased need to prioritize spending on the most impacted communities. In addition, now is the time to utilize the full set of resources of philanthropy by increasing asset payout and employing various investment strategies to provide much needed capital to Black communities.

- Center Black Experience. Black leaders and communities must be engaged in the development of short and long-term philanthropic and public policy solutions to ensure that well-intentioned “helping” and reform efforts do not exacerbate existing disparities.

- Trustee Accountability. Foundation trustees are accountable for the strategic direction, fiscal health and policies implemented by the institutions for which they govern. During this time of crisis, foundation boards should take stock of the level of grantmaking to Black communities, increase targeted giving and engage in racial equity assessments of their investments moving forward. It is necessary for national Boards to do so but critically important for foundation boards in the regions hardest hit by the coronavirus with sizeable Black populations (e.g., New York, Louisiana, Michigan, Illinois, Georgia, etc.).

- Engage Black Businesses. Foundations and the public sector should actively engage Black businesses in investment management, banking and other professional services to address the pandemic’s negative impact on Black earnings and wealth.

- Lift Up Gender. The health and economic well-being of both Black people are under threat due to COVID-19; however, its impacts also differ by gender, gender identity and sexual orientation. Black women are suffering worse relative to job loss. Emerging data illustrates that Black men are at higher risk of death and racial profiling relative to COVID-19. Black LGBTQ communities are particularly vulnerable due to higher rates of suppressed immune systems and widespread housing and employment discrimination. Response efforts must take into account these differences, to ensure that all people of African descent are connected to economic opportunities, healthy and are safe from personal and state-sanctioned violence.

- Reach to the Diaspora. The racially charged impact of COVID-19 extends beyond U.S. borders. Black communities in the U.S. territories have been left out of many relief efforts and African immigrants are being targeted in both the U.S (as part of America’s Black population) and other parts of the world. During crises, we must remain vigilant of how anti-Black racism impacts people of African descent around the world and look for opportunities to unite our philanthropic efforts to save and support Black lives.

- Address Disparities in Prisons. U.S. prisons are disproportionately filled with Black and Brown people and are breeding grounds for the spread of coronavirus, other infectious diseases and, generally, hopelessness. COVID-19 relief efforts have reminded us that institutional custody should be reserved as a last resort when there is a risk of community safety or flight. That use of institutional custody must become a standard of operating in all instances. Current efforts must support the safety of those currently imprisoned, early release of incarcerated individuals and advance sustained investments in alternatives that reduce reliance on incarceration over the long-term to support Black communities.

In addition, CDP encourages you to engage in the following:

- Listen to Black leaders and follow their directions in determining what actions to take. At the same time, it is critically important that white or mainstream philanthropy be seen as stepping up and speaking out. It is not enough to just support a call to justice, we must be public, intentional and explicit.

- Institute diversity and racial justice training at your organization. Include board, staff, volunteers and community partners, including other funders. Embed diversity, equity and inclusion into your strategic plans. Review your policies and procedures as they pertain to human resources. Consider where you advertise, what questions you ask and how you facilitate diversity in hiring. Explore your grantmaking methods and processes. Who are you leaving out by the complexities of your application process? What can be done to make it more accessible?

- Support movement building and organizing by BIPOC communities. Black-led or people of color-led organizations tend to be smaller and less resourced. Provide flexible, unrestricted funding to allow money to be directed where it is needed most. Understand that small organizations can be equally or more effective as large organizations.

- Support protests. Put yourself on the frontline. Donate to the organizers of protests. Support the provision of food, diapers, medical supplies, cash, water, etc. Many of the communities most affected by police violence and racial discrimination have also been disproportionately impacted by COVID-19.

- As with most disasters, cash donations are recommended by disaster experts. Cash allows on-the-ground organizations to direct funds to the greatest area of need, support economic recovery and ensure donation management does not detract from critical needs.

Resources

Complex Humanitarian Emergencies

CHEs involve an acute emergency layered over ongoing instability. Multiple scenarios can cause CHEs, like the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the man-made political crisis in Venezuela, or the conflict in Ukraine.

Is your community prepared for a disaster?

Explore the Disaster Playbook