Overview

While often thought of as long-term heavy rain over a specific area, a monsoon is actually the name for a seasonal change in the direction of the prevailing winds. It can bring either extremely wet or extremely dry weather to an area.

Like hurricanes, typhoons and cyclones, monsoons are a product of tropical latitudes – especially where a large land mass is close to warm waters. While those weather events measure their lifespans in days or weeks, monsoons measure their lifespans over the course of entire seasons. The North American monsoon season in the southwest United States and northwest Mexico runs from June 15 to September 30.

Monsoon seasons are generally classified as either summer or winter monsoons depending on whether the prevailing winds blow from the coast (summer) or from the interior (winter) of a continent. Summer monsoons are the weather phenomenon that is most commonly associated with the term “monsoon,” with heavy long-lasting rains.

Winter monsoons are less well-known because they generally do not bring major weather conditions. However, they blow a lot of dry air from the interior of a continent that can bring about drought, water shortages and crop failures.

Summer monsoons happen when large land masses heat up. The heat from these land masses causes the air atop the land mass to heat up and rise through the atmosphere. This creates an area of low pressure that pulls in cooler moist air, creating the right conditions for the heavy rains that summer monsoons are famous.

Winter monsoons are the reverse; water off the shore of a land mass heats up and rises, creating an area of low pressure that pulls in dry air from over the land mass down towards the water.

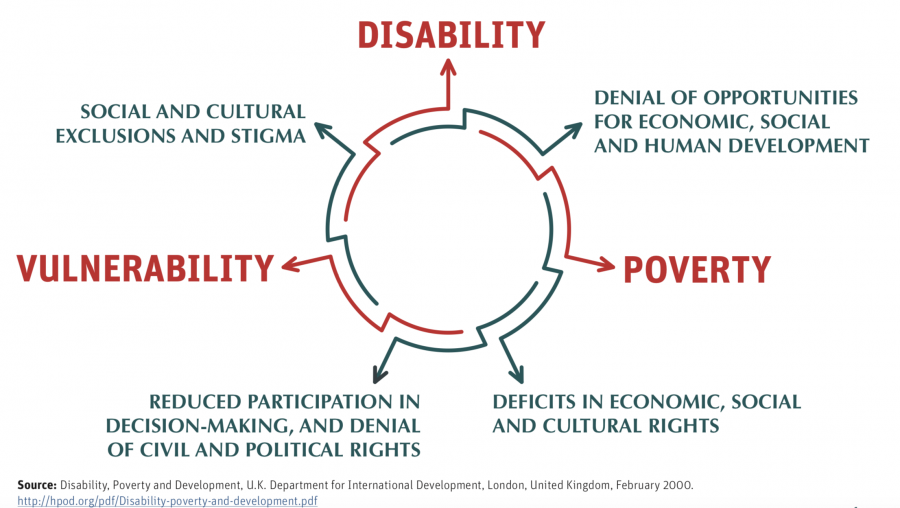

Because monsoons occur in the tropics, many of the places that are affected are both densely populated and considered to be still-developing countries that often have high levels of inequity and poverty. Summer monsoons can bring heavy rains that destroy homes, damage infrastructure, wash away crops and destroy Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) infrastructure. During winter monsoons, dry weather can lead to drought and crop failures from lack of moisture. As a result, people who are already vulnerable because of their socio-economic status, who are experiencing poverty or homelessness, or who are otherwise vulnerable are disproportionately affected by monsoons.

Key Facts

- Monsoons are both helpful and harmful. Although we often associate monsoons with harmful and destructive rain storms, the rains they bring are important for crop production. Summer monsoons in Asia are essential to bring enough water to the area to grow rice and other crops. When monsoons are stronger or weaker than normal, there can be significant problems with food security and crop production.

- Pollution and climate change are affecting the strength and predictability of monsoons. Monsoons both affect and are affected by global climate, and as the climate changes, monsoons change as well. When pollutants in the atmosphere absorb heat, they limit the amount of heating that monsoons rely on to move both dry and moist air. This means that moisture is not distributed in the same ways it has been historically, resulting in changes in precipitation across the globe.

- Monsoons are a global phenomenon. While monsoons are traditionally associated with south and southeast Asia, they also occur in Australia, many parts of Africa, and parts of North and South America.

- Natural features can be key to mitigating damage from both winter and summer monsoon seasons. Features such as mangroves, natural plants and grasses, community gardens, and other natural landscapes can help during both summer and winter monsoons. During summer monsoons, they will help absorb heavy rains while also stabilizing the ground in which they live. During winter monsoons these same features will help retain moisture in the soil, reducing the possibility of long-term drought or crop failures.

- Monsoons are not individual weather events and meteorologists are trying to change the language people use to talk about them. According to Arizona State University: “The term ‘monsoons’ as in ‘when the monsoons arrive …’ is a meteorological no-no. There is no such beast. The word should be used in the same manner that ‘summer’ is used. Consequently, the proper terminology is ‘monsoon thunderstorms’ not ‘monsoons.’”

How to Help

- Invest in resilient low-cost housing initiatives. Summer monsoons often bring devastatingly heavy rains, flash flooding and landslides that disproportionately affect people who are living in poverty and without access to resilient housing. Investing in resilient, affordable housing initiatives will allow more people to access housing that can withstand what the summer monsoon brings each year.

- Fund community scale projects to preserve and restore natural features. Mangrove forests play an important role in helping to stabilize and mitigate the effects from both summer and winter monsoons. Native forests and grasslands as well as urban forestry and agriculture projects like community gardens, natural features will help absorb heavy rains, stabilize soils and retain moisture.

- Support clean energy and pollution reduction projects. Pollutants in the atmosphere are disrupting the historic monsoon patterns while climate change is amplifying the effects of monsoon seasons. Reducing pollutants and minimizing the effects of climate change will help monsoons to return to historic and predictable patterns.

- Fund sustainable development by local entrepreneurs and businesses in regions that are affected by monsoons. Sustainable local developments that support local entrepreneurs and businesses will help them to be more resilient, better prepared and able to recover more rapidly when they experience effects from summer and winter monsoons.

What Funders Are Doing

- The Levi Strauss Foundation donated $60,000 to Oxfam America’s disaster relief in Bangladesh and India after the 2017 monsoon floods.

- A group of anonymous funders from Australia made a $5,805 donation to the UNHCR to support development of sustainable and resilient refugee encampments to minimize the risk to Rohingya refugees ahead of the 2017 monsoon floods.

- The American Jewish World Service provided the Boudha Bahunipati Project – Pariwar with a $10,000 grant to help build monsoon-resilient housing to replace homes that were destroyed as a result of the 2017 earthquake in Nepal.

- Caritas India received a $398,400 grant to support food security and agricultural recovery from Cordaid after the 2013 monsoon seasons brought both flooding and drought to the Bihar region of India.

Learn More

- CDP Issue Insight: Drought

- CDP Issue Insight: Landslides

- CDP Issue Insight: Hurricanes, Typhoons and Cyclones

- CDP Issue Insight: Floods

- CDP Issue Insight: Emergency and Interim Shelter

- CDP Issue Insight: Nutrition

- CDP Issue Insight: UN Cluster Approach

- National Weather Service – Climate Prediction Center: Monsoons

- National Park Service: Monsoon Season

- NASA Visualization Explorer: The Science of Monsoons

- UK Meteorological Office (Video): What is a Monsoon?

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Overview

Overview