Overview

If you want to create an endless debate amongst disaster researchers or responders, academics, emergency mangers, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and philanthropists, ask them to define “resilience.” Every field has its own definition and most individuals within each discipline will define it differently.

The Latin root of “resilience” means to bounce back. While this definition of resilience has been used in discussions around disasters for some time, the following four common definitions reflect a more nuanced understanding of resilience:

- “The ability of a system, community or society exposed to hazards to resist, absorb, accommodate to and recover from the effects of a hazard in a timely and efficient manner,” United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction (UNISDR).

- “The ability of a social or ecological system to absorb disturbances while retaining the same basic structure and ways of functioning, the capacity for self-organisation, and the capacity to adapt to stress and change,” Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- “The capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change,” the Resilience Alliance.

- “Disaster Resilience is the ability of countries, communities and households to manage change, by maintaining or transforming living standards in the face of shocks or stresses — such as earthquakes, drought or violent conflict — without compromising their long-term prospects,” Department for International Development (DFID), UK Aid.

In recent years, conversations regarding resilience have both broadened and deepened, expanding to incorporate elements of disaster risk reduction, development, climate change adaptation, land-use management, and socio-economic, political and ecological factors. There has also been increased emphasis placed on personal and community resilience. Funders need to determine what their definition of resilience is, what it includes (and does not include) and how it will be integrated across all their funding streams. It is no longer enough to provide immediate relief and longer-term recovery and/or mitigation for the next disastrous event. New ideas of resilience focus on a more systems-based, integrated approach that also considers sustainability despite future changes in, for example, political structure or the economy. A comprehensive resilience framework needs to include physical assets, culture and behavior. Context is also critically important. For instance, teaching women and girls to swim in coastal communities at risk of tsunamis develops their personal resilience and preparedness. It would do nothing however, for young women in Kansas, who would be more resilient by creating preparedness or evacuation kits and learning how to survive an earthquake or tornado.

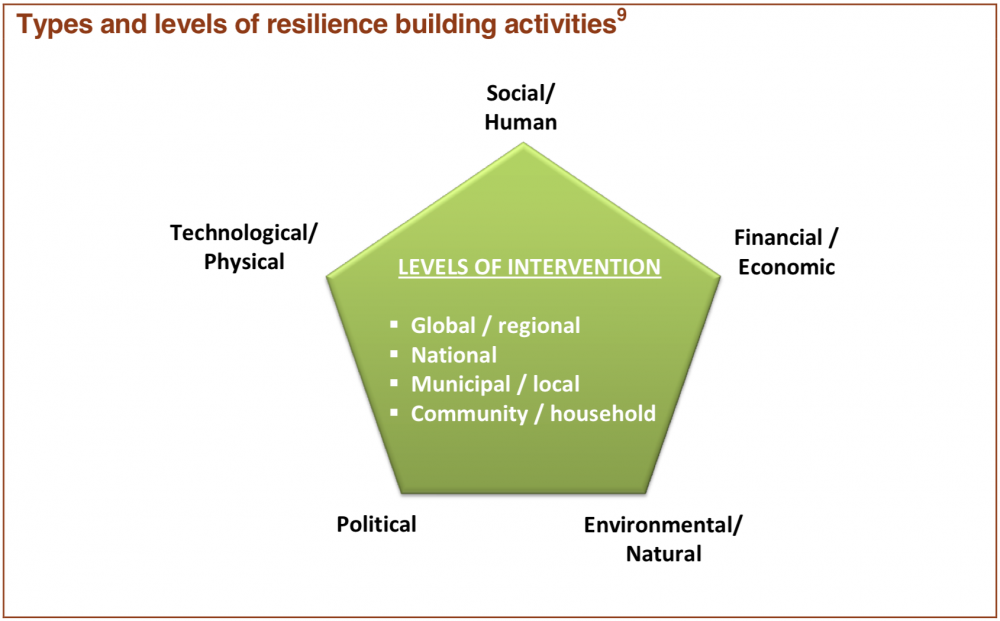

It is important to look holistically at a community to see what resources and assets are in place before a disaster that will enhance resilience after a disaster. DFID’s ‘assets pentagon’ is based on the sustainable livelihoods framework and considers the social, human, physical, financial and natural resources and assets at play.

Key Facts

- Urban areas continue to grow at a rapid pace. Climate-related natural disasters continue to be on the increase—and the costs of recovery continue to rise, as well, especially in urban areas. While only 10 percent lived in cities in 1913, currently 55 percent of the world’s population lives in urban areas. The UN estimates that an additional 2.5 billion people could be added to urban centers by 2050, bringing the total percentage to 68. Of this growth, 35 percent will occur in China, India and Nigeria. And when the urban growth has been quick, the related structures and assets may also be more vulnerable.

- The impact of climate change continues to grow. It is estimated that the economic cost of extreme weather, triggered by climate change, is likely to rise from $240 billion annually to $360 billion annually, over the next decade, in the U.S. alone.

- The cost of recovery from disasters is also increasing. Munich Re estimated that the costs of disasters in 2018 was $160 billion, above the average of $140 billion, but below the $360 billion recorded in 2017. They also report that the number of people killed – 10,400 – is high but lower than the average, leading them to believe that “measures to protect human life are starting to take effect.”

How to Help

- Building the resilience of individuals and communities before a disaster is of great importance. The goal of disaster recovery is often stated as restoring a community to the way they were before the disaster struck. However, for communities that were facing great social challenges such as poverty, an affordable housing shortage, crime etc., it is better to look at how to make them even better and to address some of those challenges as part of recovery.

- Work to change the conversation about disaster risk reduction. Not all disaster risk reduction efforts are as beneficial as they could be—especially when they fail to consider potential changes in communities, economies and leadership over time.

- Focus on efforts that are ahead of the curve. Disaster philanthropy continues to happen primarily in the immediate wake of a catastrophe. However, efforts that reduce the impact of disasters – in addition to shoring up a community’s ability to rebound and adapt — can offer more “bang for the buck.”

- Understand that resilience is not just about individual traumatic events or disasters. Communities also can be affected by, for example, a manufacturing plant closing, which leaves a large percentage of the population in a more vulnerable state.

- Support efforts that are holistic in their approach. Back in 2012, Lucy Bernholz encouraged the philanthropic community to start listening for talk of resilient organizations rather than sustainability strategies. “Resilient leaders (and leadership) will be next,” she wrote in her blog, Philanthropy 2173. “Yes, it’s a buzzword. But with all the change taking place, and the uncertainty that comes with it, focusing on adaptability and bouncing back seems like a good idea. The word might become buzz, but the idea and capacity are the keys to evolution and survival.”

- Encourage better collaboration between the academic community that wants to focus on research and the NGOs that can bring efforts to life. As the conversation about resilience continues to come to the forefront, support convenings, creative thinking and inclusive, holistic approaches. Achieving resilience requires action and funders can help by supporting efforts that lead to positive, enduring forward movement.

- Invest in organizations that are building up resilience capacity. Look at what organizations are doing to create sustainability and reduce future risk, not just how they are solving the immediate crisis at hand.

- Invest in leadership of local, grassroots, community organizers. Community organizing is making a comeback and philanthropy is showing its support for organizing that begins at the ground-up. Starting at the local level and involving a wide variety of players is a great strategy to build comprehensive, community resilence. Asset-based approaches recognize that there is untapped potential in many communities and organizing can help bring those strengths to the forefront.

- Support core funding for your local Voluntary Organizations Active in Disaster (VOAD) network. Sometimes as Community Organizations Active in Disasters (COADs) these groups bring together disaster response organizations and help provide coordinated response. They are usually underfunded and need core, administrative support to do their best work. (See CDP’s VOAD Issue Insight or Playbook piece for more information).

Here are a few principles to keep in mind when funding resilience. Ensure your grant dollars are going to projects that are:

- Sustainable over time, yet adaptable to future changes in for example, the region’s politics and economy. These things can all impact an NGO or a funder’s ability to continue engagements.

- Contextual. “Resilience” is such a broad term that it can be applied in a variety of ways; consider what is relevant and responsive.

- System-based and holistic. At the same time, responsibilities—and accountability—must be clear.

- Inclusive and participatory. Multi-stakeholder resilience planning is the foundation of effective resilience building.

- Consider vulnerabilities of people, incorporating both tangible and intangible elements of human behavior. Consider the impact of chronic stress through, for example, poverty in a community—and how that could impact that area’s ability to withstand a catastrophic event.

What Funders Are Doing

- Lord Mayor’s Charitable Foundation gave in 2017 to Echo Youth and Family Services’ Ready2go Cockatoo program. Ready2go Cockatoo is community-led disaster resilience program that supports people living independently in the Hills region of the Dandenong ranges who are unable to adequately safeguard against the effects of extreme heat & other emergencies. The program matches vulnerable residents with volunteer community members who can provide information, support an early relocation, prior to high-risk events, including visitation checks, especially in urban and peri–urban settings.

- The Rockefeller Foundation gave $1 million in 2015 to BRAC USA Inc., to support providing subsidized financial services to poor and informally employed communities in Sierra Leone and Liberia in an effort to build resilience to the Ebola epidemic and to strengthen internal capacity to deliver services in periods of crisis.

- The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust made multiple donations in 2015 and 2016 to World Vision, totaling over $2.5 million to support flood mitigation and community resilience in Amhara, Ethiopia.

- In 2015, The Kresge Foundation gave the Los Angeles Alliance for a New Economy a $660,000 grant over three years to ensure that climate-resilience investments made by the City of Los Angeles are maximized and reach those communities most impacted by climate stressors such as extreme heat and drought

- Beginning in 2017, the Latino Community Foundation co-designed with local Latino-serving community organizations impacted by the North Bay Fires in the San Francisco region to deploy $1.3 million to meet the immediate needs of Latino families, strengthen Latino-led nonprofits and build lasting community for a just and equitable recovery.

Learn More

- PreventionWeb: Resilience

- Resilience Matters: Strengthening Communities in an Era of Upheaval (book)

- Resilience to Disasters: A Paradigm Shift from Vulnerability to Strength

- Defining Disaster Resilience: A DFID Approach Paper

- Building Community Resilience to Disasters: A Way Forward to Enhance National Health Security

- Hyogo Framework for Action 2005-2015: Building the Resilience of Nations and Communities to Disasters

- The Australian Natural Disaster Resilience Index

- Community and Regional Resilience Institute

- Mercy Corps: Resilience, Development and Disaster Risk Reduction

- UNISDR

- The Rockefeller Foundation: Resilient Cities

We welcome republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

The

The

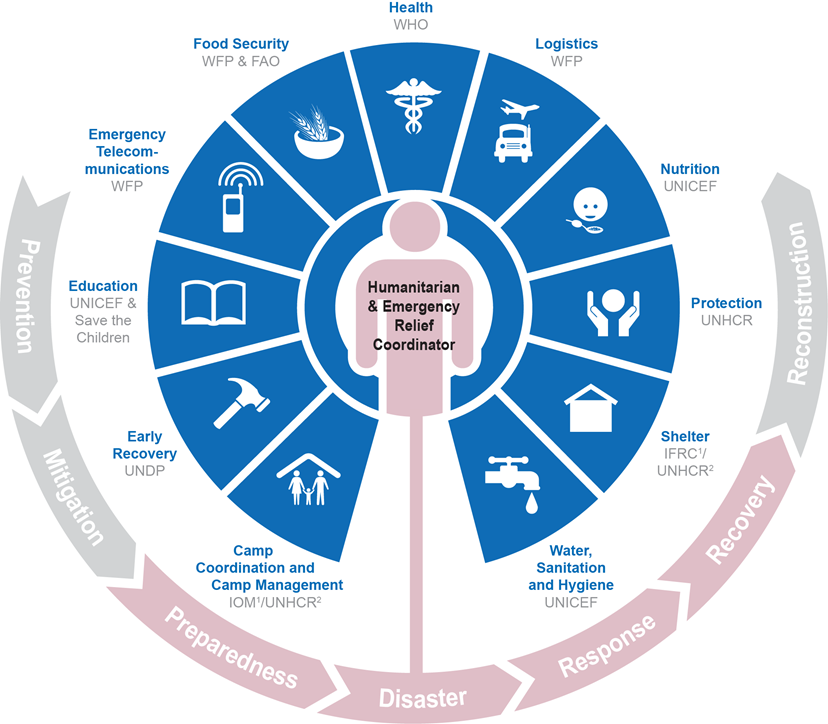

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) principles are of tremendous concern in everyday life, but can be heightened during an emergency or disaster. With systems potentially damaged, access to water can be quite limited. Sanitation often comes to the forefront when displaced persons live in camps—especially overcrowded ones. WASH issues are multi-faceted even in the best of times. Access to water is a consideration, but so too is the quality of the water. Sanitation challenges may be vastly different in urban and rural areas across countries. And even more developed nations are not immune from disease spread by poor hygiene practices.

Water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) principles are of tremendous concern in everyday life, but can be heightened during an emergency or disaster. With systems potentially damaged, access to water can be quite limited. Sanitation often comes to the forefront when displaced persons live in camps—especially overcrowded ones. WASH issues are multi-faceted even in the best of times. Access to water is a consideration, but so too is the quality of the water. Sanitation challenges may be vastly different in urban and rural areas across countries. And even more developed nations are not immune from disease spread by poor hygiene practices.