Famine

According to the United Nations’ definition, a “famine” has taken hold when: at least 20 percent of households in an area face extreme food shortages; more than two people in 10,000 are dying each day (from both lack of food and reduced immunity to disease); and more than 30 percent of the population is experiencing acute malnutrition.

Overview

According to the 2024 Global Report on Food Crises, nearly 282 million people in 59 countries or territories were in crisis or acute food insecurity (IPC/CH Phase 3 or above, or equivalent) in 2023. This figure is an increase of 23.8 million people from 2022.

While hunger and food insecurity are prevalent worldwide, famine is only declared when certain conditions are met and catastrophic impacts are evident.

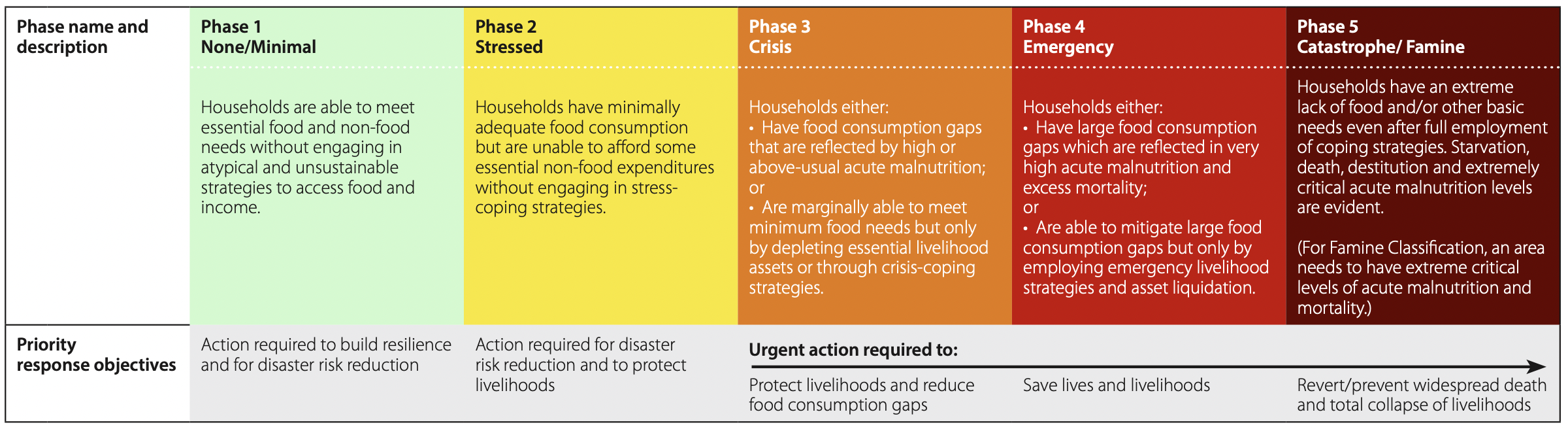

The United Nations (UN) uses a five-phase scale known as the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC) to assess a country’s food security situation.

A famine classification is the highest on the IPC scale (Phase 5) and is attributed “when an area has at least 20% of households facing an extreme lack of food, at least 30% of children suffering from acute malnutrition, and two people for every 10,000 dying each day due to outright starvation or to the interaction of malnutrition and disease.”

Famine is generally declared by the UN based on multistakeholder consensus in conjunction with the affected country’s government. Thus, it is political in nature. However, people can be living in famine-like conditions or meet some of the classification’s criteria long before a declaration of famine is made. Therefore, it is critical to act early to save lives. It is more difficult to recover and regain productive assets when famine is reached.

In addition to the IPC, the Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) provides early warning and analysis of acute food insecurity around the world to agencies who plan for and respond to humanitarian crises. The FEWS NET expected levels of food insecurity are classified using the IPC. These institutions provide critical analyses that allow for detection, early warning, early action and, ideally, famine prevention.

Famine is a more complex problem than a shortage of things to eat; it is a challenge of markets and distribution, the result of a long, slow decline in access to food. That decline may occur for any number of reasons, including climate-related disasters (such as drought), conflict, political, social and economic policies, chronic under-development, weak governance, and poor management or a lack of resources and humanitarian assistance.

The famine cycle may be triggered by a particular disaster event but it is often a combination of these factors that pushes a country or a region into famine.

Previous Famine Classifications

Since the IPC classification system was established in 2004, there have been three formal declarations of famine:

- Sudan (August 2024): After more than 15 months of war, famine was declared in Zamzam camp in the North Darfur region, home to 400,000 displaced people. At the time of the declaration, the Famine Review Committee (FRC) warned that other parts of Sudan risked famine if urgent action was not taken.

- South Sudan (February 2017): Famine was declared in parts of Unity State, following three years of civil war that devastated the country’s economy. An estimated 80,000 people faced famine conditions and another one million people classified in Emergency (IPC Phase 4)

- Somalia (July 2011): Famine was declared in parts of Southern Somalia, the Afgoye corridor IDP settlement, and the Mogadishu IDP community. Due to a confluence of conflict, drought, and poor rains, an estimated 490,000 people were classified in IPC Phase 5 (Catastrophe/Famine).

Much can be done before hunger turns into a crisis of such catastrophic proportions. Disaster preparedness, early warning and early action can help prevent food insecurity and famine. In short, early action works.

Key Facts

- Most famines can be, and are, predicted well in advance. By the time warnings of famine appear in news media, various factors have been exacerbating the situation for years or even decades. Communities already “on the edge” can be pushed over that edge with a large event, such as a surge in conflict, or a sequence of events, such as several seasons of low rainfall resulting in prolonged drought and failed harvests.

- Conflict can worsen global hunger. According to the Global Report on Food Crises 2024, conflict and insecurity was the most significant driver of food insecurity in 20 countries or territories where 134.5 million people were in IPC Phase 3 or above or equivalent. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 demonstrated the role that regional conflict plays in worsening global hunger. Ukraine and Russia provide a third of global wheat supplies, and experts warned that the food supply impacts from the invasion would be long-lasting. In March 2022, UN Secretary-General António Guterres said that developing countries were struggling to recover from the COVID pandemic and now “their breadbasket [was] being bombed.” One year later, the war continued to negatively impact global food security.

- Breaking the cycle of famine requires more than emergency aid and assistance from external agencies. The most effective famine prevention comes through ongoing partnership with those in the affected communities, investment in local capacity and longer-term solutions and shoring up resources and strategies in advance of a crisis while still respecting local culture. Funding for lifesaving assistance remains critical but funders should also act with urgency to build resiliency at the same time and ultimately break the hunger cycle for at-risk communities.

- There are no quick-fix solutions to famine. Just as a famine does not occur overnight, neither does its resolution—or the prevention of another famine in the same area. Philanthropic efforts must take a risk-based approach and a long-term view in addition to meeting the immediate lifesaving needs of starving populations, which is often too little and too late.

How to Help

Donors seeking to provide disaster relief and to reduce the risk of famine altogether can:

- Use financial and other resources to combat poverty and structural inequalities that create the conditions for famine.

- Support local organizations and actors that are close to the populations at risk of famine. They will be the ones that know what works and what does not, and they will be the ones potentially facing repeated cycles of famine risk.

- Take a two-track approach and balance support for immediate needs with preparedness and resilience-building efforts.

- Fund research into the underlying causes of famine in various areas.

- Fund research into the effectiveness of mitigation, adaptation and resilience programming to determine what strategies and approaches work in preventing famine and what do not.

- Develop strategies to mitigate future disasters in partnership with well-established, well-connected actors in famine-prone communities.

- Invest in agricultural technologies and methods of bolstering crops that reduce environmental harms. Rotation of crops, for example, can help prevent the degradation of soil.

- Invest in innovative food storage and distribution systems. Famine does not necessarily mean no one has food; it may mean that some have food and some do not, but a lack of communication and/or access prevents food from reaching those most in need.

- Support the scaling up of climate resilience across food systems, including investing in climate-smart agricultural practices and solutions to adapt and respond to the effects of climate change.

- Be mindful of early warning systems of food insecurity and famine. Maintain a proactive stance by monitoring the next possible crises using resources such as FEWS NET.

- Government policies often help push at-risk populations into crisis. Outside intervention and advocacy can help raise awareness to avert famine.

What Funders Are Doing

- CDP’s Sudan Humanitarian Crisis Fund supports vulnerable, marginalized and at-risk groups to help prevent and address famine and build longer-term solutions to help communities recover.

- CDP’s Global Hunger Crisis Fund mobilizes support to prevent and address extreme hunger and malnutrition and their urgent, life-threatening impacts. Efforts are focused on long-term recovery and building resilience to current and future conflict, climate-related drought and food insecurity.

- CDP provided $50,000 to Citizen to Citizen Development Organization – Ethiopia (C2C) in 2024 through its Global Hunger Crisis and Global Recovery Funds to implement community-led drought response in highly food insecure regions of Southern Ethiopia, including training and small grants to community-identified projects. This extended Survivor and Community Led Response (SCLR) initiatives that launched with an initial $250,000 award in 2023.

- CDP provided $500,000 to ASAL Humanitarian Network, hosted by ALDEF – Kenya, in 2023 through its Global Hunger Crisis and Global Recovery Funds to support recovery and resilience to hunger in drought-affected communities through accelerated grassroots-driven mitigation, preparedness and community rebuilding action in 10 arid and semi-arid counties in Kenya.

- CDP provided $250,095 to NEXUS Consortium Somalia in 2023 through its Global Hunger Crisis and Global Recovery Funds to increase the ability of drought-affected farmers from marginalized communities to adapt to and manage climate risks.

- CDP provided $250,000 to Concern Worldwide in 2023 through the Global Recovery Fund, Global Hunger Crisis Fund and COVID-19 Response Fund to improve resilience capacities among vulnerable pastoral and agro-pastoral households to respond to and cope positively with the effects of the current drought and future climatic shocks in Turkana and Marsabit Counties, Kenya. The grant builds on the success of a previous grant to Concern Worldwide in the area and will expand to include the formation of village savings and loans associations to strengthen economic inclusion. CDP’s previous grant and the project’s results led to investments from another donor.

Learn More

- CDP Disaster Profile: Sudan Humanitarian Crisis

- CDP Blog Post: CDP launches a Sudan Humanitarian Crisis Fund

- CDP Webinar: “From pets to heroes: the role of animals in disaster response and recovery”

- CDP Issue Insight: Resilience

- IPC – Famine Facts

- World Food Programme

- International Food Policy Research Institute

- The Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET)

- The Global Report on Food Crises 2024

- Tufts University – Friedman School of Nutrition Science and Policy: Feinstein International Center

- World Hunger Education Service

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.