Venezuela has been in a severe socio-political and economic crisis for several years.

With an exodus of more than 7.72 million people since 2014, the refugee crisis in Venezuela is the largest displacement crisis in Latin America and one of the largest in the world.

Several root causes generate this unprecedented flow of migrants and refugees, including a deep economic crisis, repression and democratic breakdown in Venezuela. Venezuelans face a variety of challenges in receiving countries. With the sometimes tumultuous changes in governments in Latin America, Venezuelans prefer to leave receiving countries rather than go through another national crisis. Since these elements will remain throughout the year, migration flows are expected to continue and even increase in 2024.

Of the 7.72 million people, almost 84% settled in Latin America and the Caribbean and faced significant challenges accessing food, housing and livelihood. Some choose to return to Venezuela due to the abovementioned challenges. A Ministry of Foreign Affairs video claims that over 300,000 nationals have returned since September 2020. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), many are motivated to return to Venezuela by the perception of an improving economic outlook, family reunification and the lack of integration, including experiences of xenophobia and intolerance.

The 2023-2024 Regional Refugee and Migrant Response Plan (2024 RMRP) is a regional strategic response plan and advocacy tool focused solely on addressing the immediate humanitarian and protection needs of Venezuelan refugees and migrants. Meanwhile, the 2024-2025 Humanitarian Response Plan (HRP) articulates how humanitarian partners and funders respond to the assessed and expressed needs of the affected population within Venezuela.

(Photo: Refugees from Venezuela have set up their own informal camp in Boa Vista, Brazil. Credit: Michael Swan; CC BY-ND 2.0)

The multidimensional crisis in Venezuela began after mass protests erupted in 2014 in response to hyperinflation, lack of essential services and insecurity. Authorities responded through disproportionate use of force, torture and sexual violence to quelch protests, which continued into 2019 at the start of President Nicolas Maduro’s second term. Political infighting and some foreign government support for the 2018 opposition leader, Juan Guaido, led to a protracted political crisis and an already failing economy.

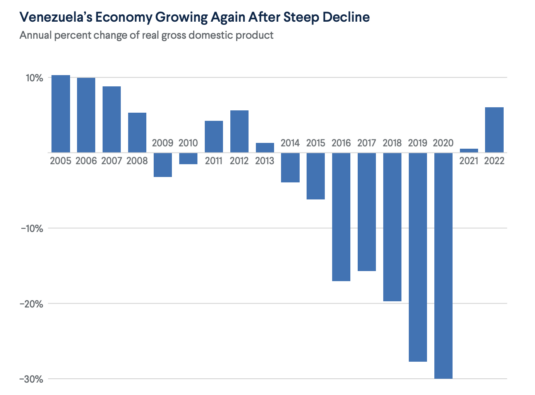

The significant decline in crude oil prices, from $100 a barrel in 2014 to less than $30 a barrel in 2016, meant that Venezuela’s oil-dependent economy, or “petrostate,” could no longer finance itself. Despite recent improvements in Venezuela’s economy, the country risks worsening relations with the U.S. after President Maduro reneged on a deal to hold fair and free elections in 2024. The U.S. pulled back sanctions relief on Jan. 29, 2024, and as of March 13, 2024, additional measures are also being considered against the Maduro regime. This leaves 27.2 million Venezuelans facing a political, humanitarian and economic crisis with deteriorating healthcare, hyperinflation and food insecurity.

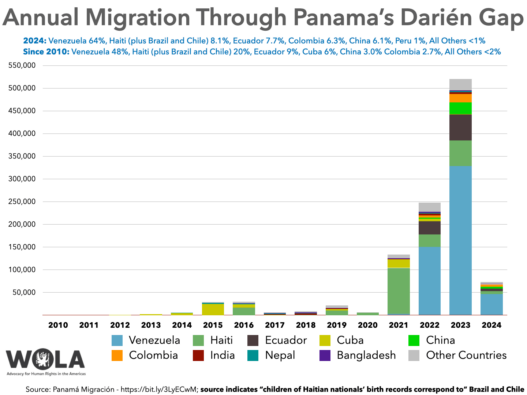

As of November 2023, a majority of refugees and migrants in Latin America and the Caribbeans are located in Colombia (2.9 million) and Peru (1.5 million). An increasing number of Venezuelans are also reportedly heading north through the dangerous Darién Gap, the only land route to the U.S. from South America.

It is important to note that many host governments do not account for individuals without regular immigration status. This means the number of Venezuelan refugees and migrants could be much higher than officially reported and published.

Latest Updates

Announcing Global Recovery Fund Grants to Yemen and Venezuela

Key facts

- Of the 7.72 million Venezuelan refugees and migrants, 6.5 million people are in Latin America and the Caribbean. According to an updated 2024 RMRP, integration, food security and protection were identified as the top needs of Venezuelans in transit. This varies for Venezuelans in their intended destination and non-Venezuelans in transit.

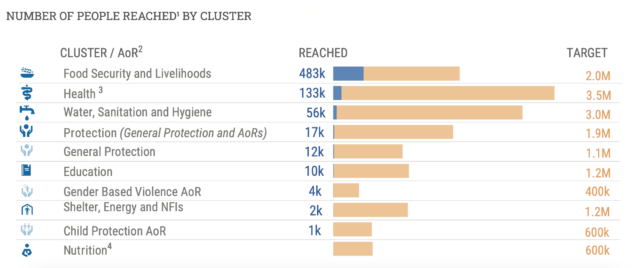

- Within the country, the extended 2024-2025 HRP indicates that health, food security, water, sanitation and hygiene, and protection are top priorities for humanitarian aid partners.

- Among the nearly 520,000 people who entered Panama via the Darién Gap in 2023, more than 328,000 were refugees and migrants from Venezuela.

- The 2024-2025 HRP plans to reach 5.1 million people out of 7.6 million people with humanitarian needs in With a financial requirement of $617 million, as of March 13, 2024, it stands at $5.7 million with just under 1% of the plan funded.

- Nearly 82% of the population lives in poverty, and 53% in extreme poverty with an income insufficient to access basic food. Severe food insecurity is expected to persist through September 2024, while millions of households continue to experience acute food insecurity due to climate-induced incidents and economic factors. In addition to food security and livelihoods, the HRP found Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH), health, and protection to be some of the top indicated needs.

- Venezuela’s economy has improved, with hyperinflation dropping to 190% in 2023 compared to 234% in 2022 and projected economic growth of 8% in 2024.

- Venezuela will hold presidential elections on July 28, 2024, despite an election ban on opposition leader Maria Corina Machado. This leaves President Maduro expected to run for a third term without the possibility of a strong opponent.

- The clampdown on civil society and human rights since the era of former president Hugo Chavez escalated to a forced closure of the local United Nations human rights office in late February 2024. This comes after efforts to control civil society through a legislative bill passed in mid-January, severely limiting nongovernmental organizations’ activities, funding and freedom.

Deteriorating socioeconomic conditions

Venezuela’s freefall economy is one of the biggest drivers of the internal humanitarian crisis and the exodus. The country has the world’s largest oil reserves, which financed almost 58% of the government’s budget. However, after oil prices plunged by over 70% in 2016, Venezuela went into an economic and political spiral mainly attributed to oil sanctions.

Sanctions, specifically from the U.S., have caused some of Venezuela’s darkest times of economic and humanitarian crisis. Critics say sanctions have increased disease and mortality rates, worsened widespread hunger, exacerbated economic decline and accelerated the migration crisis.

The economy contracted by 80% between 2014 and 2021, causing large-scale migration out of the country. Hyperinflation is one of the steepest in Latin America despite some economic growth in 2023.

The economic decline has left nearly 85% of Venezuelans in poverty while 53% in extreme poverty. The minimum wage has remained at 130 bolivars a month, equivalent to just $3.6 since 2022. With the average monthly salary at $24, a basic food basket for a family of five costs $500, nearly impossible to access. Food insecurity is one of the highest needs in and outside the country.

Economic decline, poor water management and climate change have led to a water crisis affecting 90% of Venezuelans. The President of the Venezuelan Health Observatory says, “There is a close correlation between the regions of Venezuela with the highest levels of food insecurity and those that report serious water supply failures.”

A 2022 study by Johns Hopkins University for the Simón Bolívar Foundation found that the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated Venezuela’s already devastating health and health care system due to years of political and economic crisis. The country was also found to have decreased life expectancy rates, increases in maternal and infant mortality rates and low vaccination coverage, leading to a resurgence of many vaccine-preventable diseases like measles.

Refugees and migrants also face inadequate access to basic water and sanitation services.

According to experts, data from 2023 suggests a more positive outlook and projection of the economy along with slowing inflation, even though the deterioration of salaries and collapse of public services still pose significant problems. It is a commonly accepted understanding that relaxing sanctions could stabilize Venezuela’s economy and help alleviate some of the humanitarian crisis that led millions to leave the country.

Migration

The U.S. is a destination for many Venezuelan migrants and refugees passing through Central America and Mexico. Many resort to dangerous travel methods, including by boat or the treacherous 60-mile (97-kilometer) Darién Gap between Panama and Colombia. In 2023, a record 520,000 migrants crossed the Darién, with Venezuelans making up almost 63% of all migrants.

Migrants risk death, human trafficking and violence at the hands of criminal groups, in addition to dehydration, diseases and hunger. Over 20% of those crossing the Darién were children, and UNICEF estimates half of the children who crossed between January and June 2023 were just under five years old.

This “migration industry” is a multi-million dollar business that supports everything migrants need to make the treacherous journey.

To make matters worse, in early March, Panama forced Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) to suspend all assistance to migrants arriving through the Darién Gap after a clash over a spike in sexual violence across the Darién. MSF is the only organization providing comprehensive medical care to victims of sexual assault. In 2023, 676 migrants sought medical care for acts of sexual aggression in the Darién. In January 2024, 120 cases were registered, a monthly increase of 100%.

In the U.S., the Biden Administration granted temporary protection statuses to an estimated 472,000 Venezuelans in September 2023. Shortly after, the administration restarted direct deportations to reduce unlawful crossings through the southern border. Between October and December 2023, more than 1,300 Venezuelans were returned until flights were canceled in January 2024 by the Maduro government.

In Fiscal Year (FY) 2023, nearly 335,000 Venezuelans entered the country via a land crossing. After Mexicans, Venezuelans were the second-largest nationality stopped at the U.S. border, surpassing Cubans, Guatemalans and Hondurans.

So far, in FY 2024 (October 2023 – January 2024), just under 164,520 Venezuelans attempted to cross into the U.S. at a land border crossing.

Due to legal requirements, many refugees and migrants resort to irregular migration routes and risk dangerous conditions, such as smugglers and traffickers. These routes can also lead migrants and asylum-seekers to be denied entry, detained and expelled from territories – a clear violation of the non-refoulement principle under international human rights law.

In addition to barriers to accessing essential services, many in host countries without legal status and rights also experience challenges when accessing protection services, including legal justice, psychological support, family reunification and support for survivors of gender-based violence (GBV).

The 2023 RMNA also found migrants and refugees experience higher accounts of climate-induced disasters, violence, xenophobia and discrimination due to their status and place of origin, causing further barriers to access services.

Upcoming elections

Venezuela’s presidential elections are expected to occur on July 28, 2024. However, even before the October 2023 presidential primaries, there were concerns that Maduro was already fixing the process and eliminating the possibility of a fair vote. This included dismantling the national electoral council in June 2023.

The Supreme Justice Tribunal’s decision to suspend the results from the October 2023 presidential primaries came after opposition leader Maria Corina Machado secured more than 90% of the votes. In addition, the Supreme Courtblocked Machado from holding office.

Hindrances to free and fair elections have led the U.S. to roll back sanctions relief made in October 2023 after Maduro committed to work toward free and fair presidential elections in 2024.

Venezuelans in the diaspora and within the country eagerly track presidential elections. A poll funded by PAX sapiens, a philanthropic foundation based in Colorado, found that economic stabilization and improvement were insufficient for migrants to return. It found that:

- More than 57% would likely return if the economy significantly improved, while just 14% would do so if Maduro remains in power despite economic improvement.

- Approximately 65% of Venezuelans would return if the opposition won the 2024 presidential elections.

- If given the opportunity, out of 444 migrants surveyed, over three-quarters would vote for opposition leader Maria Corina Machado.

Human rights organizations and humanitarian aid experts warn that the people of Venezuela may continue to suffer significant humanitarian needs due to the deteriorating economy and repressive policies.

A two-pronged approach is required to support the crisis in Venezuela.

- The situation within Venezuela is dire, and the needs are immense. To support the needs of Venezuelans within the country, funders should focus on funding local actors or international NGOs with humanitarian access.

- As a result of the immense displacement, many host countries need philanthropic assistance to help support the affected countries. Humanitarian, development and human rights partners also need support to respond to the many needs of displaced Venezuelans.

As of the most recent update via UNOCHA, some of the most significant gaps in reach can be seen in Health, Water, Sanitation and Hygiene, Food Security and Livelihoods and Protection.

Cash assistance

The Center for Disaster Philanthropy recommends cash as a donation method and recovery strategy. Direct cash assistance can allow families to purchase items and services that address their multiple needs. It gives each family flexibility and choice, ensuring that support is relevant and timely. Cash-based approaches to disaster recovery also give people the freedom to choose how they rebuild their lives and provide a pathway to economic empowerment. In countries with a functioning market system, cash transfers allow people to purchase supplies according to their needs.

Cash donations to nonprofits (rather than supplies, except where directly requested) are recommended by disaster experts as they allow for on-the-ground agencies to direct funds to the most significant area of need, support economic recovery and ensure donation management does not detract from supporting disaster recovery needs and quickly re-establishing access to basic needs.

Food assistance and livelihood

Within Venezuela

The cost of a basic food basket, an indicator used to track staple food prices over time to measure inflation, increased by 350% between October 2022 and October 2023. As of April 1, 2024, the average monthly salary is $24, and a weekly food basket for a family of four costs 1,202.50 bolivars ($34.52).

Despite ranking 75 out of 121 countries with moderate hunger levels on the 2023 Global Hunger Index, 2.5 million people were projected to face crisis and higher levels of food insecurity by January 2024. According to Famine Early Warning System Networks (FEWS NET), Venezuela will continue to experience acute food insecurity until September 2024.

Rising inflation and severe weather incidents are two primary drivers of food insecurity. As a result, harmful coping strategies have been reported, such as child labor, reduced meal size or certain food items, and more people, especially women, selling essential items as part of the informal economy.

Projected economic growth of 5% in 2024 and a more stable hyperinflation are expected to improve food access and livelihoods. However, unpredictable climate incidents can impact the supply of national and imported food, food prices, and livelihoods. Small farmers and Indigenous communities’ food security and livelihoods are gravely affected by climate-induced incidents.

Current responses range from providing nutritious school meals and direct household food distribution to technical assistance and training to protect, maintain and create livelihood opportunities.

WFP’s six-month projection of funding needs from March to August 2024 is $60.7 million, representing about 63% of total needs.

Outside of Venezuela

Among Venezuelan migrants and refugees living in a host country, 6.91 million people need assistance, while only 1.21 million are targeted through the 2024 RMRP. The highest needs are recorded in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador, respectively.

Socio-political instability affecting several countries and potential climate-induced conditions are anticipated to impact food production and regional food systems. These conditions are intrinsically linked to food security and the lack of economic opportunities for refugees and migrants. Insufficient access to livelihood-generating activities prevents many from affording the needed meals and nutrition, causing malnutrition and stunting.

In and out of the country, Venezuelans continue to need nutritional support and food supplementation. This can include providing meals, distribution of high-energy, portable, emergency rations at migration checkpoints, vouchers to purchase local food in Venezuela or receiving countries, and agricultural support. In addition to emphasizing agrarian livelihoods through capacity-building and training, the 2024 RMRP highlights using in-kind support and cash and voucher assistance to support food security. Since 2019, UNHCR has delivered cash assistance to over 700,000 Venezuelans across the region.

Receiving countries, in particular, need support in providing integrative and inclusive services and strategies. The 2024 RMRP plans to increase campaigns and capacity-building response strategies focusing on working with host communities and integrating Venezuelans into national social protection networks. This can allow refugees and migrants to access employment opportunities through regularization and documentation.

Health care support

Within Venezuela

The recent UNOCHA Situation Report from December 2023 highlights the need to ensure the availability of medicines, medical and surgical supplies and equipment specifically for vulnerable populations with infectious diseases. Critical needs also remain for strengthening surveillance of respiratory diseases and access to medicine and specialized care such as mental health, cancer and other serious non-communicable diseases.

In addition to the needs mentioned above and ongoing efforts, vaccination coverage is direly needed, especially among vulnerable populations like Indigenous communities and people with disabilities. Continued provision of nutrition supplements and strengthened feeding practices, food hygiene and waste management can help prevent the emergence of malnutrition and health cases.

With reports of structural underfunding and understaffing, limited materials and medicine, regular blackouts and water shortages in health centers, critical gaps exist in the procurement and distribution of goods and access to fuel and permits for movement of staff and supplies. Other critical areas for support include family planning, long-term health system recovery, and investment through local and national NGOs.

Outside of Venezuela

Health is an issue for almost 49% of Venezuelan migrants and refugees, particularly in Colombia, Peru and Ecuador, according to the 2024 RMRP.

The 2023 RMNA found that many migrants and refugees faced unique obstacles in receiving health care in their host countries. Specific challenges include fear of rejection at health centers, lack of health insurance and valid documentation, and lack of information on accessing health systems in their respective host countries.

The Johns Hopkins University study for Simón Bolívar Foundation also reported increased health risks such as sexual and gender-based violence (GBV) and untreated pre-existing medical conditions during migration. Similar to the experiences of globally displaced populations, Venezuelan migrants and refugees face a high burden of infectious diseases, chronic noncommunicable diseases and psychiatric illnesses.

Ongoing critical needs include investment in health care prevention measures and increased specialized medical care such as mental health, focus on the health and wellbeing of women and girls, including Indigenous communities, the establishment of mobile clinics in rural and transit areas, increased vaccine access and infectious diseases and lastly, more investment in local organizations.

Investment in health care systems and programs that support access to appropriate legal status and public health care systems are key priorities and needs.

Protection

Within Venezuela

One of the most significant gaps and needs is the lack of funding available to carry out protection prevention and response services. This is particularly true for responding local and national organizations that specialize in GBV and the protection of children and adolescents. While the Protection cluster reached 87,291 people, including 4,319 Indigenous people and 1,324 people with disabilities between September and October 2023, severe limitations still exist in the availability of services and access to rural communities.

Other critical needs include building the capacity of local responding and specialized organizations, access to legal documentation for returnees, and strengthened specialized protection services for those, especially children, at risk of recruitment into non-state armed groups, extortion, and human trafficking.

Outside of Venezuela

The 2024 RMRP found that 48.9% of all Venezuelan migrants and refugees needed protection assistance. This does not include an additional 19.1% of Venezuelan children who need protection.

Ensuring access to humanitarian organizations, especially along migratory routes like the Darién Gap, is vital for migrants and asylum-seekers in transit who view these organizations as lifelines for essential services like hygiene kits, food, water and medical assistance. Failure of governments to ensure humanitarian aid and services along routes can be devastating, as seen recently by the suspension of MSF in Panama.

For migrants in receiving countries, long-term support for employment, health care and housing are required. Due to the high percentage of Venezuelans in an “irregular situation” (lack of legal status in the host country), they may not access needed services, increasing vulnerabilities.

Expanding access to legal status can help mitigate risks of abuse, exploitation and other human rights violations. A formal regularization process, such as the regulation policy in Colombia in 2021, can help facilitate livelihoods, self-sufficiency and integration. More local, community-based protection activities, such as those that strengthen refugee and migrants’ integration and social cohesion with host communities, can have a positive impact in the long term.

The RMRP Protection sector also plans to expand the use of multi-purpose cash and voucher assistance to support GBV survivors.

Support for vulnerable populations

The extension of the HRP outlines vulnerable populations such as older people, children, people with disabilities, migrants, refugees, returnees, adolescents and young people, LGBTQI+ people, and women.

Given the vast number of vulnerable groups, critical needs include providing humanitarian aid and programming relevant to each specific population’s needs. This will prevent harmful coping mechanisms such as those outlined under food assistance. Many of these groups will also require specialized health and protection services, as mentioned in the Johns Hopkins University study from 2022.

GBV and abuse are becoming increasingly more apparent in Venezuela and outside the country. As a result, the extended HRP included gender equality as one of its key priorities. This means the incorporation of gender in all activities, promotion of gender-transformative programming, and capacity-building of local female and LGBTQI+-led organizations.

A 2023 report by the International Rescue Committee analyzed data gathered from GBV prevention and response programs implemented by NGOs across Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela. It found that “Psychological violence was the most frequently mentioned type in most countries, accounting for 43% of cases in Ecuador, 78% in Peru, and 65% in Venezuela.”

Physical violence was very close behind. In fact, in May 2023, Colombia declared a national emergency due to the escalation in violence against women. Women who live amid humanitarian crises and conflict are at an even higher risk, particularly true for women who have been displaced along migration routes and in the places where they settle.

Addressing GBV and the unique needs of vulnerable groups will be critical for humanitarian partners.

WASH

Within Venezuela

Various assessments by UN agencies and partners found that over 85% of the population cannot access sufficient water daily. Compounded by the worsening economic situation, almost 71% of the population cannot afford hygiene products.

As of March 19, 2024, humanitarian partners reached 56,000 people out of a targeted 3 million. The WASH cluster aims to support and improve hygiene practices and essential services through health facilities, schools, learning centers and within homes and communities. One of the top priorities also includes hospital waste management training.

In the most recent OCHA situational update, the WASH cluster reached 5,898 people between September and October 2023. Similar to the 2024 HRP goals, many activities focused on hygiene promotion, water treatment and safe water storage, WASH infrastructure support and training within communities, health care facilities, and schools.

To mitigate the impact of poor infrastructure and water supply, partners must continue providing water treatments, building WASH infrastructure and conducting waste management training. As the cluster has indicated, comprehensive and multi-sectoral interventions may allow greater reach and impact.

Outside of Venezuela

The 2024 RMRP found 5.6 million migrants in need of essential WASH support and currently plans on reaching 507,000, or 9.1% of people in need. Humanitarian partners will also utilize a direct assistance response modality despite reducing direct assistance activities due to the closure of WASH support spaces and funding reductions.

Refugees and migrants face inadequate access to essential water and sanitation services. Many live in overcrowded urban and rural areas, leading to increased risks of water-borne diseases and water scarcity. For example, in Colombia, an estimated 58% do not have regular access to water, and 39% reported open defecation practices.

Water scarcity and hygiene are disproportionately worsened following extreme weather events, especially among refugee and migrant settlements. For many on the move, significant challenges include accessing hygiene supplies due to financial barriers and inadequate facilities that negatively impact their health, dignity and quality of life.

In many host communities, including Indigenous people, the increasing arrival of migrants and refugees has generated stress on existing WASH facilities.

Inadequate waste management and sanitation conditions are a growing concern within informal settlements where refugees, migrants and vulnerable host communities live. Many reports of a lack of sustainable waste management practices adversely affect their health and environment.

In addition to continued direct assistance, distributing essentials like WASH kits is imperative to support migrants and refugees in transit, particularly women and children.

CDP’s Global Recovery Fund provides donors with opportunities to meet the ongoing and ever-expanding challenges presented by global crises.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you would like to make a donation to the CDP Global Recovery Fund, need help with your disaster-giving strategy, or want to share how you’re responding to this disaster, please contact development.

(Photo: A group of children arriving to a community lunch preparation as part of the recovery and rebuild humanitarian aid program. Credit: Jose Luis Molero / The Wayuu Taya Foundation)

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO or a donor, please send updates on how you are working on recovery from this disaster to Tanya Gulliver-Garcia.

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Philanthropic and government support

In October 2022, CDP provided a $200,000 grant to the Wayuu Taya Foundation, which supports the Indigenous Wayuu people located primarily along the Guajira Peninsula on the Colombia and Venezuela border. Through this grant, CDP worked with Wayuu Taya to develop an entrepreneurial model for sustainable water solutions that will continue generating income and allow them to build wells in remote indigenous communities, schools and health care centers along the border for years.

This grant is the second CDP grant to Wayuu Taya. The first grant, for $100,000 in 2020, had an outsized impact. Wayuu Taya Foundation’s President, Patricia Velasquez, attributes much of their success – shown in this video – to that first grant to build their first well, from which their other programming, including sustainable water, agricultural farming, training programs and school hygiene programs stemmed. After CDP’s initial grant, the Wayuu TayaFoundation was able to leverage this to secure more partnerships with many other international funders. This demonstrates what a huge impact can come from even small investments in organizations seeking to implement local, long-term solutions in their communities.

CDP provided a $250,000 grant in August 2022 to International Medical Corps from its COVID-19 Response Fund to improve COVID-19 vaccine access in remote Indigenous communities in the Cedeño municipality of Bolívar state in Venezuela by providing logistics support to transport and store vaccines, donating equipment to hospitals to store vaccines; strengthening the capacity of local vaccinators; and raising awareness about COVID-19 vaccines through community activities.

Simón Bolívar Foundation Inc., the nonprofit private foundation of CITGO Petroleum Corporation, awarded seven organizations $1.68 million in grant funding as part of its Colombia-Ecuador-Peru Humanitarian Health Grants program in November 2022. These grants were designed to support projects addressing “the health needs of the vulnerable migrant community and host populations in Colombia, Ecuador and Peru … The projects are estimated to benefit more than 30,000 people in need, including mothers and children, train more than 300 health professionals and provide more than 270,000 healthy and nutritious meals.”

The Ford Foundation has made several grants to support work in Venezuela, including a $2 million, two-year grant in 2022 to the Pan Health America Organization to increase equitable access to COVID-19 vaccines and diagnostic and clinical care for populations in situations of vulnerability in the Americas. They also provided a $500,000 grant in 2021 to People in Need to create a Venezuelan Resilience Fund to enable civil society organizations and human rights defenders in Venezuela to overcome the challenges generated by closing civic space and the consequences of COVID-19. A 13-month grant of $110,000 was made in 2021 to openDemocracy Limited to expand coverage and reporting on the Venezuelan crisis, including the closing of civic space, the migration exodus and the consequences of the complex humanitarian emergency on vulnerable populations of ethnic communities and women. A grant in 2020 for $90,000 to Grupo de Trabajo Socioambiental de la Amazonía, Wataniba, supported the protection of the rights of the Yanomami and Uwottja People as they struggle against the effects of illegal mining, COVID-19 and the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis.

Since 2017, U.S. foreign assistance in response to the crisis in Venezuela has totaled $2.9 billion in humanitarian aid. In addition to $376 million in aid in September 2022, the Biden Administration announced nearly $451 million in humanitarian assistance to support those affected by the Venezuelan regional crisis in November 2023. This new assistance will provide direct relief for those in the country and support Venezuelan refugees and migrants in host communities across the region.

During the Mexico City negotiations in November 2022, the Maduro administration and the opposition party had agreed “to create a $3 billion social fund drawn from various Venezuelan seized assets to invest in education, healthcare and infrastructure repairs. The UN will be in charge of distributing the money while a Venezuelan joint commission would follow and verify its correct implementation.”

In October 2023, the United Nations Secretary-General Antonio Guterres approved for the UN to start administering the new fund to address emergency needs in Venezuela. The fund is estimated to be progressively unfrozen, starting with $600 million. The latest rollback of sanctions relief by the U.S. could impact the status and administration of the UN fund.

The 2024 HRP is only 1.6% funded, requiring an additional $607.4 million. The Government of Switzerland is the largest single donor, covering 3.7% of the funding requirement.

By the first half of 2023, Venezuela’s HRP was the second most underfunded globally, with just 14% of the required funding. After advocacy work by humanitarian partners with donors, the HRP was 52% funded by the end of the year.

The 2024 RMRP has reached 2.1 million out of the targeted 3.41 million people as of March 5, 2024, and stands at 22.1% funded ($378 million out of $1.72 billion).

Related resources

Complex Humanitarian Emergencies

CHEs involve an acute emergency layered over ongoing instability. Multiple scenarios can cause CHEs, like the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the man-made political crisis in Venezuela, or the conflict in Ukraine.

Children and Youth

For children and youth, disasters can take both an emotional and a physical toll, different from how those disasters would affect adults.

Women and Girls in Disasters

Pre-existing, structural gender inequalities mean that disasters affect women and girls in different ways than they affect boys and men. The vulnerability of females increases when they are in a lower socioeconomic group.