The Horn of Africa is facing a deepening humanitarian crisis driven by climate change, conflict, and economic instability.

While definitions of the region vary, this disaster profile focuses on Somalia, Kenya, Ethiopia, Sudan and South Sudan. The Center for Disaster Philanthropy (CDP) also maintains disaster profiles for the Ethiopia Humanitarian Crisis, Sudan Humanitarian Crisis and South Sudan Humanitarian Crisis, as well as a Famine Issue Insight.

According to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA), “The Greater Horn of Africa faces a convergence of increasingly recurring and intensifying climate crises, mainly drought and flooding, conflicts, disease outbreaks, and economic shocks. These, including the impact of El Niño conditions, are driving millions of people into displacement, acute food insecurity and malnutrition, public health emergencies, and destitution.”

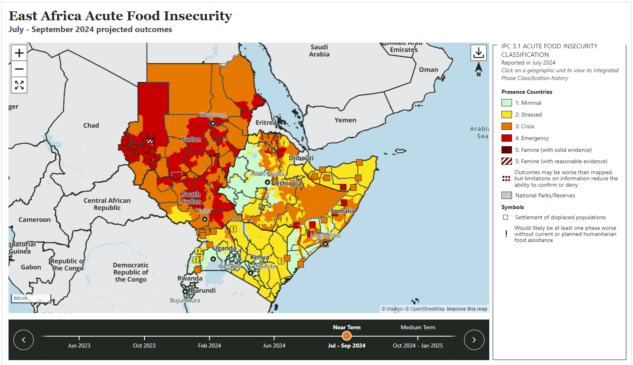

Regionally, a deepening food insecurity crisis has worsened for the fifth consecutive year, with approximately 25% of the population experiencing high levels of acute food insecurity in 2024. This trend is fueled by the conflict in Sudan, where famine was declared in parts of North Darfur in June 2024, and is projected to last until the end of October 2024.

While the region faces a multitude of humanitarian needs, international actors have identified a window of opportunity to address an escalating hunger crisis and avert large-scale catastrophes by scaling up funding and expanding humanitarian access.

(Women in Ethiopia waiting for water to be trucked in. Women and girls walk up to 10 hours to fetch water. Credit: European Union; Silvya Bolliger 2022; CC BY-ND 2.0)

Latest Updates

What we’re watching: Weekly disaster update, April 1

Women and girls eat the least and last

June is a month for Pride and refugee awareness: Q&A with ORAM’s CEO

We need tools: Reflections from my trip to Kenya

A forgotten crisis

Key facts

- The Horn of Africa has, in recent years, experienced its worst drought in 40 years. The devastation wrought by the 2020-2023 drought crisis will be acutely felt for years to come.

- In August 2024, continued above-average rainfall constituted the wettest season of the 40-year historical record in parts of Sudan and Ethiopia, resulting in severe flooding. In Greater Darfur and the northeast of Sudan, more than 170,000 people were displaced, and over 130 people were killed in the collapse of the Arba’at Dam.

- With nearly 64 million people in need of humanitarian and protection assistance across the Horn of Africa, the region accounts for close to 22% of global humanitarian needs in 2024.

- FEWS Net estimates that over 50 million people need humanitarian food assistance in the East Africa region through September 2024. Agricultural production is anticipated to somewhat alleviate food assistance needs in some areas by October 2024, but 40-50 million people will likely continue to need assistance through January 2025.

Food insecurity and livelihoods

According to FEWS NET’s East Africa Food Security Outlook for July to September 2024: “In the Eastern Horn, La Niña conditions are expected in late 2024, likely resulting in below-average rains. If the late 2024 rainy season were to fail, then acute food insecurity outcomes would likely deteriorate further than currently projected in early 2024, given the relatively short recovery period since the historic drought.”

Needs remain elevated in East Africa. In Sudan, famine is ongoing in Zamzam camp in North Darfur with another 13 areas at risk.

According to WHO, the food crisis in the region is also a health crisis. In addition to severe malnutrition, disease outbreaks including cholera, measles, malaria, dengue fever and others, are rampant, exacerbated by conflict, drought, flooding, displacement and limited access to health care. Flood-affected areas in Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya have experienced a surge in water and vector-borne diseases.

Conflict and violence

The interconnection between climate, conflict and food security is more prominent in fragile or developing contexts, creating a vicious cycle that destabilizes communities. Logistic and security challenges often impede humanitarians’ access to affected people. State and non-state actors can obstruct access in the region. The Institute for Economics and Peace’s Ecological Threat Report, released in November 2023, found that a 25% rise in food insecurity increases the risk of conflict by 36%.

Countries in the region are currently experiencing high levels of political violence and instability, including the al-Shabaab insurgency in Somalia, militia and Islamist militant activity in Kenya, and the civil conflicts in Ethiopia and Sudan:

- In Somalia, al-Shabaab Islamist insurgents continue to wage a nearly two-decade campaign against Somali forces, controlling large portions of central and southern Somalia and launching deadly attacks on Mogadishu and in Kenya.

- In Ethiopia, a peace deal signed by the government and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front in November 2022 ended a brutal two-year war that displaced millions and created dire humanitarian conditions in the Tigray region. However, recovery and the resumption of services there will take time as conditions are exacerbated by volatile climate conditions and extended drought. For more, see our Ethiopia Humanitarian Crisis profile.

- Sudan is experiencing “the largest humanitarian crisis on the face of the planet.” Since the start of the conflict in April 2023, the country now faces the worst levels of acute food insecurity in its history, with more than half of its population – 25.6 million people – in acute hunger, and more than 8.5 million people facing emergency levels of hunger (IPC 4). Over 10 million people have been displaced and more than 75% of health facilities are non-functional in conflict-affected states. More information is provided in our Sudan Humanitarian Crisis profile.

Displacement

As of June 2024, the East and Horn of Africa and the Great Lakes (EHAGL) region was host to 5.4 million refugees and asylum-seekers, and 20.8 million people internally displaced by conflict and climate-related disasters. The displacement caused by the conflict in Sudan is the largest humanitarian emergency in the region, having displaced more than 10 million people, including more than 7 million new IDPs and at least 2 million refugees and returnees in neighboring countries.

“The conflict in Sudan has triggered the world’s largest crisis, with more than half the population struggling to put enough food on their plates every day. Violence and insecurity have driven millions of people to seek refuge within their own country and in neighboring countries which are already grappling with high levels of food insecurity and instability. This is putting even more pressure on limited humanitarian resources,” says Rukia Yacoub, Deputy Regional Director for Eastern Africa, World Food Programme.

IOM calls the Horn of Africa one of “the busiest and riskiest migration corridors in the world” due to hundreds of thousands of people traveling in an irregular manner, often relying on smugglers to facilitate movement along the Eastern Route through Djibouti and the Southern Route through Kenya.

The impacts of the 2020-2023 drought are expected to keep depleting the resources in host countries, limiting their ability to support migrants along the routes and driving more people to migrate irregularly.

Drought and climate shocks

The Horn of Africa is still grappling with the lingering effects of the worst drought in 40 years and the impact of floods that happened in the second half of 2023, which further eroded fertile lands and killed remaining livestock. Recovery is expected to take between half to nearly a decade for those who lost between 80% and 100% of their livelihood.

The prolonged drought has damaged soil, making it challenging to absorb the rain to grow crops. Caroline Wainwright, a climate scientist at Cardiff University in the United Kingdom, said the flooding does not simply undo three years of drought.

Early warning systems designed to warn against various hazards would help with limiting the impacts of climate-fueled disasters in the long run. According to the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction, “Countries with substantial to comprehensive early warning system coverage have one-eighth the disaster mortality of those with limited or no coverage. Sadly, only 40% of Africa is covered by such systems, and even those are compromised by quality issues.”

Impacts on women and children

According to UNOCHA, “Millions of children and women’s lives are at heightened risk of death and other long-term consequences due to high rates of malnutrition. Acute food insecurity, conflict, and a high prevalence of infectious diseases are contributing to high rates of malnutrition, aggravated by El Niño-induced flooding in 2023 and the lingering effects of the drought.”

Across the broader Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD) region (which includes Uganda and Djibouti), there are 11.4 million acutely malnourished children under 5 years of age, of which 2.8 million are suffering the most severe form of wasting. Women and children make up the majority of the displaced populations in Sudan, South Sudan, and Ethiopia. Persistent underlying drivers of acute malnutrition among women and children, including lack of food, inadequate services, and poor infant and young child feeding practices, continue to be exacerbated by escalating conflicts, economic shocks, and the effects of weather extremes like the 2020-2023 drought.

A two-track approach is required to respond to the urgency of the moment and invest in longer-term solutions.

- The situation in the Horn of Africa is already an emergency; therefore, donors must act immediately by increasing funding for lifesaving assistance.

- While funders respond to support immediate relief efforts, they should act with the same urgency to build resiliency at the same time and ultimately break the hunger cycle for at-risk communities in the region. Timeline anticipatory action and climate crisis mitigation measures are critical.

Urgent assistance with early action

Immediate humanitarian assistance, including cash, food and nutrition treatment programs, is urgently required to mitigate the impact of the hunger crisis.

Some lessons from past droughts have been implemented, including an improvement in early warning systems, years of resilience investments and enhanced coordination. However, responses are still underfunded, and this is likely to persist. Anticipatory action, which aims to act before the onset of a predictable shock, is growing in prominence. This early action is faster, more dignified and more cost-effective than traditional humanitarian response. Such pre-emptive humanitarian interventions can save lives and livelihoods. More flexible funding is needed, an opportunity for philanthropy, to adequately prepare for shocks and increase local resilience to hazards overall.

Livelihood support

Improving livelihoods and building resilience are critical. Funders must act quickly to support emergency, recovery and resilience programming to save lives and strengthen affected communities. While humanitarian calls to action rise when areas reach IPC Phase 4 and above (emergency and catastrophe/famine phases), more focus is needed on IPC Phase 3 to prevent people from progressing to worsening phases that have catastrophic impacts on lives and livelihoods. Investments made in IPC Phase 3 are most cost-effective and help strengthen resilience. Re-establishing assets and livelihoods once they are already lost requires significant time and resources.

Livelihood support may include restoring lost livelihoods, diversifying livelihoods, introducing drought-resistant crops and supporting local market development. The FAO says saving livelihoods saves lives, “but livelihood support is disproportionately underfunded and every USD 1 spent on protecting rural livelihoods can save USD 10 spent on food-related humanitarian assistance later on.”

Cash assistance

As with most disasters and emergencies, cash donations are recommended by disaster experts as they allow for on-the-ground agencies to direct funds to the most significant area of need, support economic recovery and ensure donation management does not detract from disaster recovery needs.

CDP recommends cash both as a donation method and a recovery strategy. Providing direct cash assistance can allow families to purchase items and services that address their multiple needs. It gives each family flexibility and choice, ensuring that support is relevant and timely. Cash assistance can also help move families faster toward rebuilding their lives.

In response to the global food crisis, the WFP says that cash provides the opportunity to save and change lives by putting people in charge of buying the essential goods and services they need. The agency sends money to people in drought hotspots to spend on essentials like livestock while keeping the money in-country and circulating in the local economy.

The CDP Global Hunger Crisis Fund focuses on preventing and addressing hunger and malnutrition, building resilience to drought and food insecurity, and supporting longer-term solutions. The CDP Sudan Humanitarian Crisis Fund supports vulnerable, marginalized and at-risk groups to help prevent and address famine and build longer-term solutions to help communities recover.

Contact CDP

Philanthropic contributions

If you have questions about donating to the CDP Global Hunger Crisis Fund or CDP Sudan Humanitarian Crisis Fund, need help with your disaster-giving strategy or want to share how you’re responding to this disaster, please contact

(Photo: An internally displaced woman in Somalia receives food. Credit: Karel Prinsloo, WFP via Flickr; CC BY-NC 2.0)

Recovery updates

If you are a responding NGO, please send updates on how you are working in this crisis to tanya.gulliver-garcia@disasterphilanthropy.org.

We welcome the republication of our content. Please credit the Center for Disaster Philanthropy.

Philanthropic and government support

CDP has made several grants through its Global Recovery Fund and Global Hunger Crisis Fund from 2022 to 2024, including:

- $50,000 to Citizen to Citizen Development Organization – Ethiopia (C2C) to implement community-led drought response in highly food-insecure regions of Southern Ethiopia, including training and small grants to community-identified projects. This extended survivor and community-led response (SCLR) initiatives launched with an initial $250,000 award in 2023.

- $500,000 to Arid Lands Development Focus to provide recovery and build resilience to the hunger crisis in drought disaster-affected communities through accelerated adoption of Survivor and Community Led Response in 10 arid and semi-arid land counties in Kenya.

- $250,000 to Concern Worldwide to improve resilience capacities among vulnerable households to respond to and cope with the effects of the current drought and future climatic shocks in Turkana County, Kenya. In April 2023, CDP staff visited Turkana County to learn how the ongoing drought has exacerbated the hunger crisis and witnessed how this grant helped return barren fields to successful crop harvests. Another $475,000 grant was made to Concern Worldwide in 2023 to expand on this work in the region, including strengthening economic inclusion through the formation of village savings and loans associations.

- $250,095 to NEXUS Consortium Somalia to improve household livelihood security and increase the ability to adapt and manage climate risks among drought-affected farmers from marginalized communities in Somalia’s Baardhere and Gabiley districts. Two local nongovernmental organizations will receive subgrants and this grant will also invest in the capacity of NEXUS Consortium by funding two positions and support costs.

- $750,000 to Mercy Corps to respond to the devastating socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 and the compounding effects of the severe drought in the Horn of Africa, which has led to a food security crisis and potential famine early warning in Ethiopia, Somalia and Kenya.

- $109,471 to Adeso to implement a Survivor and Community Led Response approach in highly food insecure regions of Somalia through issuing small grants to community-identified and community-led projects.

- $500,000 to the International Rescue Committee to build community and local institutions’ resilience against recurring disasters and food insecurity by improving the capacities of drought and conflict-affected smallholder farmer households (especially women and youth), communities and their institutions to respond to and proactively mitigate disaster risks and adapt to long-term trends of food insecurity.

Resources

Complex Humanitarian Emergencies

CHEs involve an acute emergency layered over ongoing instability. Multiple scenarios can cause CHEs, like the civil wars in Syria and Yemen, the man-made political crisis in Venezuela, or the conflict in Ukraine.

Famine

According to the United Nations’ definition, a “famine” has taken hold when: at least 20 percent of households in an area face extreme food shortages; more than two people in 10,000 are dying each day (from both lack of food and reduced immunity to disease); and more than 30 percent of the population is experiencing acute malnutrition.

Drought

Drought is often defined as an unusual period of drier than normal weather that leads to a water shortage. Drought causes more deaths and displaces more people than any other disaster.